Ontario’s public service heads back to the office, meaning more traffic and emissions

For 15 years and counting, my commute from Mississauga to Toronto has been mired by...

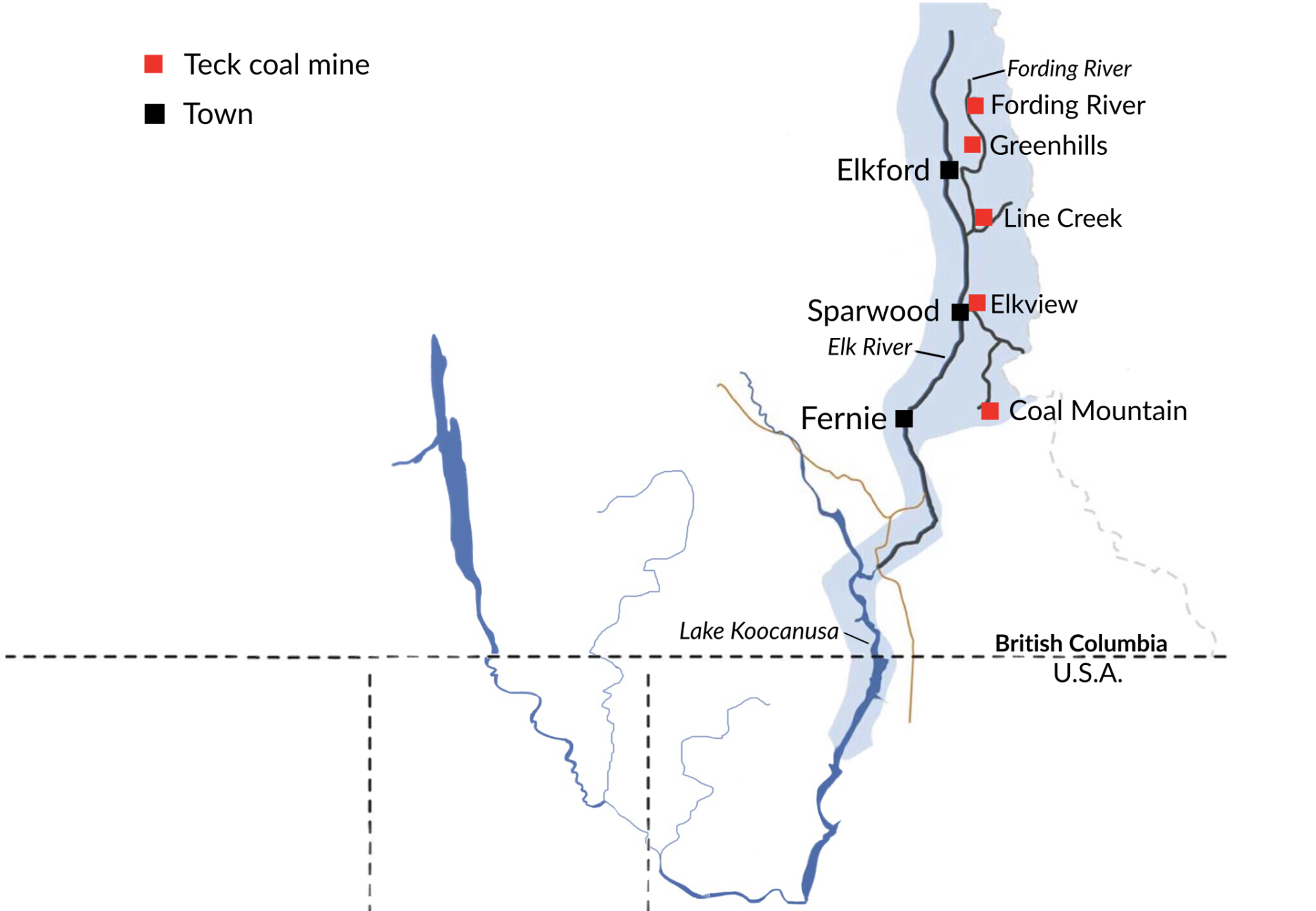

Fernie, B.C. — A Teck Resources proposal to significantly expand the largest coal mine in British Columbia is raising questions about the province’s willingness to address the legacy of selenium pollution affecting fish in the Elk River, which feeds into a transboundary watershed shared with Montana.

Selenium pollution emanating from Teck’s five metallurgical coal mines has increased steadily in recent years despite warnings the contaminant could lead to the collapse of sensitive species like the locally treasured westslope cutthroat trout.

Teck recently reported a dramatic collapse of cutthroat trout directly downstream of the company’s Fording River Operations, a sprawling mining complex referred to by employees as “the mothership” that covers more than 5,000 hectares in the Elk Valley in the province’s southeast corner.

The Castle Mountain expansion project would see the construction of an additional mine at the Fording River site, converting an additional 2,500 hectares into open, terraced pits and waste rock piles and extending the life of the mine for decades, according to Teck.

Teck submitted an initial project description for the proposed expansion with B.C.’s Environmental Assessment Office in May and a public comment period on the proposal will remain open until June 22.

Teck’s expansion plans — which could begin as early as 2026, according to a presentation prepared for officials — come amid growing tensions between Canada and the United States over selenium pollution in the Kootenai River basin.

Selenium, a naturally-occurring chemical element commonly found in coal-rich deposits, is essential to human cellular function in very small doses but can be fatal to egg-laying animals, including fish and birds, even in small quantities. In trout such as those in the Fording River, the mineral causes deformities and reproductive failure. It has been known to do so since at least the early 1980s — when selenium in agricultural runoff caused mutations in waterfowl in California — and made headlines in 2012, when selenium pollution caused by mining operations in Idaho led to the birth of a wild, two-headed trout.

Selenium levels from Teck’s Elk Valley mines are monitored under the Elk Valley Water Quality Plan by both the company and by the province of B.C.

Under the Elk Valley plan, the province allows Teck to continue operating its mines as long as the company is working toward a long-term plan to stabilize selenium levels by 2023 and reduce levels after 2030.

Yet despite Teck’s inability to stabilize or decrease the overall levels of selenium in the valley’s waterways, the province continues to grant the company operating permits.

In a statement emailed to The Narwhal, the B.C. Ministry of Environment and Climate Change Strategy said that all mines in B.C. are regulated “to ensure comprehensive regulatory oversight throughout the life of a project.”

“The potential for cumulative effects of existing mining in the Elk Valley, including potential cumulative effects from selenium, will be carefully considered during the environmental assessment process administered by the [Environmental Assessment Office],” the statement reads. “If an environmental assessment certificate is issued for the project, these potential effects and proposed mitigation measures would be considered as part of a robust permitting process.”

Yet a lack of faith in the province’s capacity to effectively regulate selenium pollution is leading to increasing calls for a federal review of Teck’s proposed expansion.

A May 15 joint letter submitted by leadership of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes and the Kootenai Tribe of Idaho to Canada’s Minister of Environment and Climate Change, Jonathan Wilkinson, urged the federal government to undertake a comprehensive environmental assessment of the project at the federal level.

“Selenium is poisoning our fish from these mines upstream, and that is not acceptable,” Shelly Fyant, chairwoman of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes, said at a public webinar the day before the joint letter was made public. “River contaminants run above any threshold considered protective of aquatic life.”

B.C.’s general water quality guidelines recommend selenium levels be kept to two parts per billion to protect aquatic life. Yet in waters throughout the Elk Valley, selenium has been measured at levels higher than 150 parts per billion.

“My concerns are sustaining clean water for future generations,” Fyant said. “These natural resources are critical to cultural practices that have existed for millennia.”

Canada’s Impact Assessment Agency has until Aug. 19 to determine whether or not to move ahead with a federal assessment.

“The Castle Project is being planned with extensive measures to ensure the environment is protected,” Chris Stannell, Teck Resources spokesperson, told The Narwhal. “We are engaging with communities, including local Indigenous Peoples, to gather feedback and ensure that the project creates mutually beneficial outcomes, while responsibly managing impacts.”

Unique B.C. trout population suffers 93 per cent crash downstream of Teck’s Elk Valley coal mines

Gary Aitken Jr., chairman of the Kootenai Tribe of Idaho, said he is concerned not enough is being done to ensure the impact of Teck’s mines is being made public.

“What’s happening now is inadequate,” he said during the May 14 webinar. “Transparency is lacking, and also the levels of enforcement are lacking as well.”

In February the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency demanded the B.C. government hand over data clarifying why Teck had been allowed to exceed guidelines for toxic heavy metal pollution.

While the safe selenium limits for aquatic life are two parts per billion, B.C.’s water quality guidelines limit selenium in drinking water to 10 parts per billion. In the U.S., the Environmental Protection Agency’s guidelines set safe limits for aquatic life at five parts per billion.

In its letter to the province, the U.S. agency noted recent research found selenium contamination from B.C. rivers — at levels four times the legal maximum for drinking water — had flowed into U.S. waterways.

Teck’s five metallurgical coal mines are all upstream of the transboundary Koocanusa Reservoir. Map: Carol Linnitt / The Narwhal

The agency expressed particular concern about Teck’s plans to expand Castle Mountain, noting it was “unacceptable that the province has accepted” the company’s plans, which acknowledge the Fording River operations would continue to exceed water quality standards.

According to spokesperson Stannell, Teck has “provided comprehensive information” to the Environmental Protection Agency. He added the company’s engagement with the U.S. agency is “ongoing” and that as a member of the Koocanusa Transboundary Monitoring Task Group, Teck uploads its own monitoring data to the agency’s public water quality database.

Teck does not release its raw water monitoring data to the public.

In late April, 22 American and Canadian scientists published an open letter in the journal Science calling Teck’s operating permit in the Elk Valley an example of Canadian authorities failing to incorporate “transparent, independent, and peer-reviewed science” in their decision-making process.

The Elk Valley Water Quality Plan, under which the Elk Valley mines operate, “allows contaminant discharges up to 65 times above scientifically established protective thresholds for fish,” the authors wrote.

They added, “upstream Canadian mines threaten downstream economies, waters, and ways of life.”

Lars Sander-Green, a mining analyst for conservation non-profit Wildsight, told The Narwhal that B.C. is hesitant to hit pause on Teck’s mining operations despite the worsening problem of selenium.

“B.C. has really given Teck whatever they’ve wanted whenever they’ve asked for anything,” he said.

Sander-Green said he sees the Castle expansion project as an open admission that water pollution can continue in the Elk Valley for decades to come, likely impacting the environment for up to a thousand years, he said, as chemicals continue to leech from the region’s many exposed waste rock dumps.

“What we’re concerned about is: what is the long-term solution? And if there’s no long-term solution on the scale of the problem, then we don’t think the project should go ahead,” Sander-Green said.

Stannell told The Narwhal that Teck is making “significant progress towards achieving the objectives of the Elk Valley Water Quality Plan.”

Teck introduced a $600-million Line Creek water treatment plant in the Elk Valley in 2014 that caused an accidental fish kill six months after coming online. The plant was taken offline in 2017 after Teck discovered the plant was inadvertently releasing a more bioavailable form of selenium into the environment, meaning it was taken up more readily by biotic life.

The plant was recommissioned in 2018, and Stannell said it is now treating up to 7.5 million litres of water per day and that the company is “seeing reductions in selenium concentrations downstream of the facility.”

Another water treatment facility at Teck’s Elkview mining operations is treating up to 10 million litres of water per day and achieving “near-complete removal of nitrate and selenium from mine-impacted waters,” Stannell said. He added another water treatment plant, with an expected capacity of 20 million litres per day, is under construction at the Fording River operations.

Despite these advances in the company’s water treatment facilities, both Aitken and Fyant said they still consider Teck’s water treatment facilities as “unverified technology” that has yet to be successful in reducing Elk Valley pollution levels.

A truck dumps waste rock at Teck’s Fording River operations in the Elk Valley. Photo: Jayce Hawkins / The Narwhal

The International Joint Commission established by the 1909 Boundary Waters Treaty, exists to resolve disputes over transboundary waters, but has yet to weigh in on the Elk Valley’s pollution problem.

Kathryn Teneese, chair of the Ktunaxa Nation Council, said her nation, whose territory covers about 70,000 square kilometres in and around the Kootenays, including the Elk Valley, has engaged the International Joint Commission on the issue of mining contamination for two decades.

Despite the many years of involvement, a fix to the selenium problem remains out of site, Teneese said. “It continues to be very challenging to find long-term solutions.”

Canadian commissioner Merrell-Ann Phare, who also participated in the May webinar, emphasized that the International Joint Commission is not a regulator or enforcement agency, but is keen “for citizens to be heard” on this issue.

The U.S. or Canadian federal government has to task the commission with making an official recommendation on the expansion project and so far this has not happened.

The last time the Boundary Waters Treaty was invoked over mine water pollution in B.C. was in 1988, when it was used to assess the environmental impact of the proposed Cabin Creek coal mine, in the Flathead mountain range adjacent to the Elk Valley and six miles north of the U.S.-Canada border. The commission found the “potential impacts” of the mine on fish populations in the U.S. so detrimental it recommended the mine “as presently defined and understood not be approved.”

The project was abandoned.

Teneese, along with other Indigenous leaders in the U.S., emphasized the urgent need for Ottawa’s involvement to regulate and monitor mining activities in the Elk Valley — one of the biggest coal-producing regions in the world — in part because only federal governments can enforce pre-existing international treaties.

Erin Sexton, a biologist for the University of Montana’s Flathead Lake Bio Station, began studying selenium in the Elk Valley in the early 2000s after being involved in assessing the biodiversity of the Flathead prior to the Cabin Creek coal mine’s rejection.

Sexton said discussion surrounding the Castle Mountain expansion project has largely excluded Canada’s federal government.

“So far decision-making has been made mostly between B.C. and the state of Montana,” she said.

The Canadian Impact Assessment Agency was unable to provide a more specific timeline on the release of its decision whether or not to subject the Castle Mountain expansion by publication time.

Sexton also pointed out that Canada currently has no legally binding regulations on effluent pollution from coal mines.

University of Montana biologist Erin Sexton takes a water sample in the Koocanusa Reservoir as part of an independent water testing program. Photo: Jayce Hawkins / The Narwhal

“I think the consequence of not having those legally binding regulations is that there’s this sliding scale in the Elk and Fording Rivers as far as regulatory enforcement. What we’ve witnessed to date is that water quality objectives are set down the watershed and as these are not met, continuously exceeded throughout the year, there is no enforcement, no response to that because the legal structure does not exist.”

Canada is working on long-delayed regulations but the most recent draft regulations to be made public propose one set of rules for almost all mines in Canada, and an “alternative approach only for existing mountain mines in the Elk Valley.”

The draft regulations note the Elk Valley has “legacy issues” and, because of “significant long-term impacts to the aquatic environment,” the region requires separate rules.

In its sustainability reports for 2017, 2018 and 2019, Teck told stakeholders it “remained actively engaged in the review process for the draft regulations” through each of those years. Critics see the draft regulation as evidence of Teck’s lobbying for a legal right to pollute.

“It seems every time there’s some sort of regulatory level or hook that may be relevant the Elk Valley mines emerge as the exception to the rule,” Sexton told The Narwhal. Sexton said B.C.’s mining reform as well as proposed regulations for metal mines and coal mines have all held the promise of an improvement in the Elk Valley.

“These processes come to a close and Teck’s Elk Valley mines are continuously exempt from the regulatory tools that result from these processes.”

Sexton added that she does not understand how this project doesn’t immediately qualify for a federal review and said it points to overarching concerns she has with the environmental assessment process in B.C. and in Canada.

In addition to the Castle Mountain expansion, there are three new mines proposed by other companies for the Elk Valley.

“We continue to have this piecemeal assessment of mines in the Elk Valley … That is inherently opposed to how we understand how watersheds work — they can’t be parsed out in discrete parts like mines are,” Sexton said.

“And it’s hard to think that’s not by design in terms of evaluating the cumulative impacts.”

— With files from Carol Linnitt

Update June 18, 2020 at 10:27 a.m. PST: This article was updated to reflect the fact that the letter written in the journal Science in late April was composed by a group of both American and Canadian scientists rather than just American scientists as previously stated. An additional update was made to correct the amount of hectares impacted by the Fording River operations. Previously this article stated these operations covered 20,000 hectares but that is for all of Teck’s Elk Valley operations and not just the Fording River operations, which cover approximately 5,000 hectares.

Enbridge Gas will face Waterloo Region in a hearing before the Ontario Energy Board to renew an agreement that would allow the company to continue...

Continue reading

For 15 years and counting, my commute from Mississauga to Toronto has been mired by...

For our last weekly newsletter of the year, we wanted to share some highlights from...

The fossil fuel giant says its agreement to build pipelines without paying for the right...