What’s scarier for Canadian communities — floods, or flood maps?

When maps showing areas most likely to flood are outdated, it puts people and property...

Editor’s note: On Thursday, May 14, 2020 the Supreme Court of Canada rejected an appeal by Taseko Mines in a decision many say is the end of the New Prosperity mine.

It’s early morning, the loons are calling into the silence of the Nemiah Valley and the glacial blue waters of Chilko Lake are cold. Very cold.

The brand-new, 21-foot Highfield boat, bought by Xeni Gwet’in First Nation to enforce Tsilhqot’in laws on Chilko Lake, docks at the pebble beach on a small island and Chief Jimmy Lulua dives in.

Where the road through the Nemiah Valley in Tsilhqot’in territory ends, Chilko Lake begins. The mountains that rise from its shores offer a stark contrast to the open landscape of the Xeni Gwet’in traditional territory. Photo: Louis Bockner / The Narwhal

A quick dry-off and Lulua is ready to give a history lesson.

“We have always owned this land. Everywhere you look belongs to us. The land is who we are as Tsilhqot’in people. We say we are people of the river, people of the blue water,” he said.

“This is not B.C., this is not Canada. The jurisdiction is ours,” he said.

Grass glows in a Nemiah Valley field backlit by the rising sun. Photo: Louis Bockner / The Narwhal

Chief Jimmy Lulua of the Xeni Gwet’in was elected in a 2018 landslide victory and is continuing the band’s decades-long fight against Taseko Mines’ proposed New Prosperity Mine at Fish Lake. Photo: Louis Bockner / The Narwhal

Neither is it the Wild West, Lulua emphasized and, Tsilhqot’in communities are working quickly to figure out how to control activities in a vast territory that, for the first time in Canadian history, has been legally acknowledged as belonging to Indigenous people who have used the land for thousands of years.

In a precedent-setting 2014 decision, the Supreme Court of Canada unanimously ruled that the Tsilhqot’in Nation held Aboriginal title to almost 1,800 kilometres of land in central B.C., southwest of Williams Lake. The title land covers the Nemiah Valley and stretches north into the Brittany Triangle, along the Chilko River and part of Chilko Lake. That means the Tsilhqot’in Nation, made up of six communities including Xeni Gwet’in, has the right to exclusive use and control of the land.

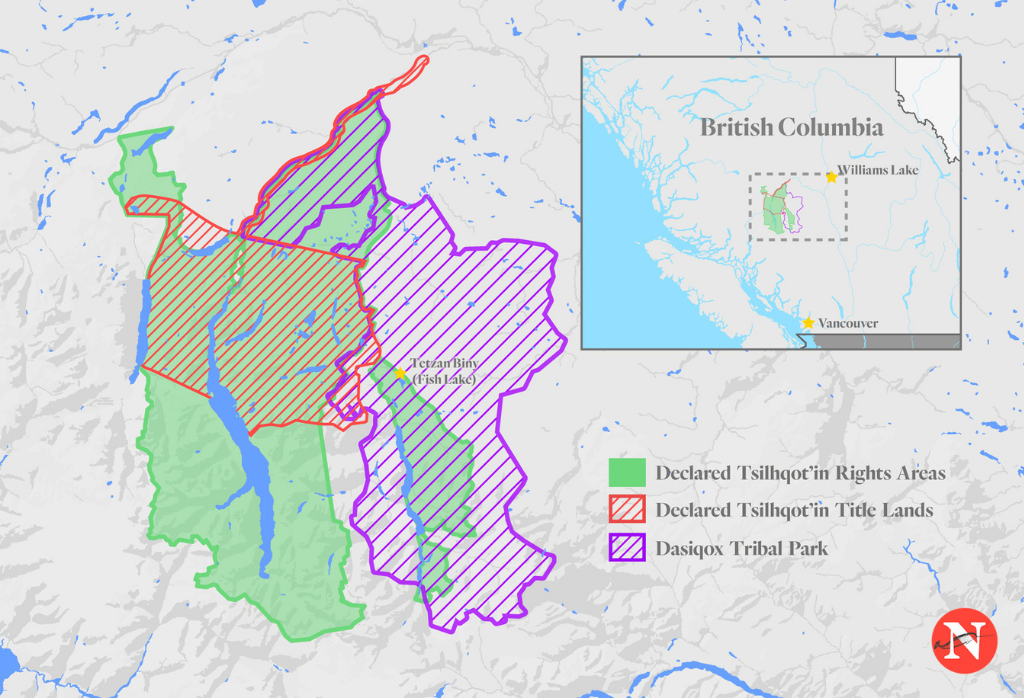

In 2014 the Tsilhqot’in won a 25-year legal battle when the Supreme Court of Canada ruled the nation held Aboriginal title to almost 1,800 kilometres of land in central B.C. A larger area has been legally declared as a place where Tsilqot’in have rights to hunt, trap, fish and trade. Taseko Mines’ proposed New Prosperity mine is within this larger rights area, and also within an area the Tsilqot’in delcared as a tribal park in 2014. Map: Dezine Studio / The Narwhal

A larger area claimed by the First Nation, including Dasiqox Tribal Park, has been legally declared as Tsilhqot’in rights land, giving the right to hunt, trap, fish and trade. But, it remains a grey area where rules can be unclear.

The rights land includes Fish Lake, known as Teztan Biny, an area of profound cultural and spiritual significance, and ground zero for an almost 30-year fight against Taseko Mines Ltd. That fight is reigniting as the mining company pushes to conduct extensive explorations while the Tsilhqot’in Nation remains adamant that Taseko equipment will not be allowed into the territory.

“Fish Lake is our most sacred area and it’s a burial ground. It’s our highest level of church in non-native terms,” Lulua said.

“What would happen if I went to Williams Lake and said I need to look through those graves because there’s probably jewelry or something there and I want to make money?”

Teztan Biny, or Fish Lake, located high in the Chilcotin Plateau near the Nemiah Valley, has been at the epicentre of a standoff between the Tsilhqot’in First Nation and Taseko Mines for almost three decades. Despite two rejections by the federal government the company continues to attempt to push forward with exploratory drilling around the lake. Photo: Jeffrey Gibbs / Tsilhqot’in national government

Taseko’s plans to build the New Prosperity mine to access a large copper and gold deposit has twice been rejected by the federal government, but — on Christy Clark’s last day in office — when Tsilhqot’in communities were on wildfire evacuation, the province granted an exploration permit to the company.

That permit, upheld by the courts, gives Taseko the go-ahead to build 76 kilometres of roads and trails, 122 geotechnical drill sites, 367 trench or pit tests, 20 kilometres of seismic lines and a 50-person work camp. It expires July 2020, but Taseko could apply for an extension.

The Tsilhqot’in Nation was caught in the crossfire as Clark left the NDP with a grenade, said Chief Joe Alphonse, Tsilhqot’in national government chairman.

Chief Joe Alphonse of the Tl’etinqox Nation stands outside the band office in Anaham, B.C. Alphonse has been outspoken in his criticism of the Taseko proposal to build New Prosperity Mine at Teztan Biny or Fish Lake. Photo: Louis Bockner / The Narwhal

“They were doing a little favour for their friends on their last day in office. That’s corruption,” he said.

The bottom line is the mine cannot be built without federal approval and Tsilhqot’in people are adamant the exploration is not going to happen, Alphonse said.

Tsilhqot’in are not opposed to development, provided it is the right project, in the right place, with consultation from the get-go and fair profit-sharing, Alphonse said, emphasizing that Taseko has not met any of the criteria.

“Societies and companies have to adapt and, with our title case, companies have to learn to work in partnership with First Nations people. Ten years from now, it’s the companies that have done so that are going to be excelling,” he said.

Some mining companies are learning to work with the new reality, agreed Chief Russell Myers Ross, Tsilhqot’in national government vice-chairman.

“But, for whatever reasons, this company has decided to ignore all ethical principles.”

Chief Russell Myers Ross of the Yunesit’in band — one of the Tsilhqot’in bands strongly opposed to the New Prosperity Mine proposal at Fish Lake — sits outside his government’s band office on the Stone Reserve, 100 kilometres west of Williams Lake. Photo: Louis Bockner / The Narwhal

The legal battle against Taseko, which has cost the First Nation millions of dollars and absorbed infinite time and energy, is one reason Tsilhqot’in leaders hope to eventually wrap the entire 4,400 square kilometres into declared title land.

“There’s no place like this,” said Lulua, gesturing at the snow-patched Coast Mountains framing the lake.

“And there’s no one that can manage this area like we can. We will definitely go for more. We are not stopping until we have 100 per cent of Tsilhqot’in territory. Our people are pretty persistent.”

Both sides are now waiting for a B.C. Supreme Court decision, expected in early September, on competing injunction applications.

“Earth is the one that’s going to save us, not Safeway.”

The applications were filed last month after Taseko workers were turned back by a Tsilhqot’in roadblock. The company is applying to prohibit the Tsilhqot’in from interfering with its exploratory drilling program, while the Tsilhqot’in national government is applying for an injunction to stop the exploration program until there is a full trial of the claim that the drilling program is an unjustified infringement of proven Aboriginal rights.

Opposition to Taseko is almost universal around the remote, off-grid Nemiah Valley. It is a community where households use solar power or generators and most residents have no wish to see power line construction or huge trucks tearing up roads where children ride horses and play and herds of horses are often found grazing along the ditches.

Outside the band office in Xeni Gwet’in, Gilbert Solomon and Alex Lulua, both residential school survivors, have little time for Taseko or any company that wants to ride roughshod over Indigenous land rights.

“If they go in there, there will be big, mucho karma. The mountain will come down,” Solomon predicted, semi-joking.

Alex Lulua (left) and Gilbert Solomon, two Xeni Gwet’in band members, stand outside the Nemiah Valley gas station. They, like almost all of the valley’s residents, are strongly opposed to Taseko’s proposed New Prosperity Mine. Photo: Louis Bockner / The Narwhal

“These people don’t know how to play nice. That’s why we don’t play with them. They are saying there will be benefits? Huh, we don’t want your stupid money. … The material world is not good. Earth is the one that’s going to save us, not Safeway. This is our Safeway,” said Solomon, gesturing at the surrounding meadows and mountains.

Alex Lulua was among those who took part in the latest blockade and is willing to stand in opposition for as long as it takes.

“We never gave up the land or ceded it. They are the greedy ones. They just want to make money. They have no respect for burial sites,” he said.

“The only good thing that would come out of a mine is that they would give us a handful of the dirtiest work. All the good work would go to people with degrees. The land is going to be lost forever and then they will leave. Look at Mount Polley.”

On August 4, 2014, a tailings pond full of copper and gold mining waste breached at the Mount Polley mine, spilling an estimated 25 billion litres of contaminated materials into Polley Lake, Hazeltine Creek and Quesnel Lake, a source of drinking water and major spawning grounds for sockeye salmon. No fines have been levied and no charges have been laid five years after the disaster.

Concern for the land and animals is echoed by Doris William, 77, who now lives in a small house in Xeni Gwet’in, but who grew up at Fish Lake living off the land.

Doris William, an elder of the Xeni Gwet’in band, lived off the land near Teztan Biny or Fish Lake between 1948 and 1972. Photo: Louis Bockner / The Narwhal

“I don’t want them to spoil the land and poison the river, but it’s hard to tell if it can be stopped. They keep coming back,” she said with a hint of resignation.

Further down the gravel road, which alternates between dust and puddles of uncertain depth, a handful of Xeni Gwet’in cowboys are roping and branding calves before heading out to inspect the growing population of wild horses with the aim of culling the infirm and identifying promising youngsters.

As the branding iron is heated in the fire and anxious calves are wrestled to the ground, Roger William, Xeni Gwet’in chief during the rights and title case, reflected on how Taseko wants to change life in the Nemiah Valley.

Mike Hawkridge, Emery Phillips and James Lulua tag and brand a calf in a pen on the outskirts of the Nemiah Valley. Photo: Louis Bockner / The Narwhal

Taseko cannot drill without impacting Indigenous rights, William said.

“It’s not a good place for a mine. They are just messing with the place. They will open the roads and then say we can’t hunt or fish out there. If they approve it, the place will be contaminated for how long? And the taxpayer will be paying,” he said.

Former Xeni Gwet’in chief Roger William photographed at a cattle pen near the entrance to the Nemiah Valley. Photo: Louis Bockner / The Narwhal

Emery Phillips, a veteran of a previous roadblock, cannot understand why Taseko keeps pushing to tear up the ground when, without federal approval, the mine cannot be built.

“You can’t eat gold and it can’t go ahead. It’s all greed. The investors want their money,” he said, breaking off to rope another calf.

Emery Phillips, a cowboy from the Nemiah Valley, takes a break before branding calves. Photo: Louis Bockner / The Narwhal

The modern day history of activism in Xeni Gwet’in goes back to 1989 when the Nemiah Declaration was first adopted, setting out firm rules for how the community saw its future — no mining or mining exploration, no commercial road building, no flooding or dam building.

And the final sentence: “We are prepared to enforce and defend our Aboriginal rights in any way we are able.”

The Nemiah Declaration was the basis for two decades of litigation, culminating in the successful ruling in the rights and title case and, in 2015, the Tsilhqot’in Nation enacted the Declaration as its first law.

Annie Williams, former chief of the Xeni Gwet’in band, holds the Nemiah Declaration of 1989. She, along with elders, lawyers and others, was instrumental in formalizing the document, which helped lead to the Tsilhqot’in’s precedent-setting 2014 victory in the Supreme Court decision that gave them rights and title to much of their traditional lands. Photo: Louis Bockner / The Narwhal

Annie Williams was Xeni Gwet’in chief when the idea of the declaration was first raised at a general assembly.

“We could see the clearcuts encroaching. At first, all we were trying to do was stop the logging that was coming up the road,” she said.

The clearcuts were an affront to people who use every part of trees harvested and take pride in leaving the area as if it had never been used, Williams said.

“Our elders always say we do not own any land, we look after the land,” she said.

Discussions with the community and elders produced the declaration, which was first written in Tsilhqot’in and then in English.

“Our elders said at the time, this is not something for us today, we need to find a way to the future,” Williams said.

Taseko’s plan for an open-pit copper and gold mine was twice rejected by the federal government, initially after a scathing Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency panel report concluded that the plan to use Fish Lake as a tailings pond would cause extensive damage to the environment and Indigenous rights.

Taseko returned with a second application that included an untested plan to cut off the water source to Fish Lake and recirculate water.

“It was a grand plan that tried to sway the powers-that-be, but that’s no way to have a lake operate. It would be nothing but a large aquarium,” said Richard Holmes, a biologist and environmental consultant who works with the Tsilhqot’in national government and Xeni Gwet’in.

Fish Lake has excellent rainbow trout used to stock other lakes and, in addition to the eyebrow-raising plan for the lake, extensive damage was done by Taseko during its exploration nine years ago when all the timber was removed, affecting drainage, Holmes said.

Once again, the panel concluded Taseko’s plan would risk unmitigable environmental damage, but before the Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency ruling, the former provincial Liberal government jumped in and gave their stamp of approval.

Pre-dawn in the Nemiah Valley where expansive ranchlands and majestic mountains meet. Photo: Louis Bockner / The Narwhal

In 2010 the B.C. Environmental Assessment Office handed Taseko a certificate which gave the company five years to start work. The certificate was renewed in 2015, but expires Jan. 14, 2020, unless there has been a substantial start. A spokesman for the Ministry of Energy, Mines and Petroleum Resources said that, if the certificate expires, the company will have to start from scratch with the Environmental Assessment Office working with the proponent to determine what parts of the expired certificate are still relevant.

Bizarrely, the exploration permit is not tied to the expiry of the Environmental Assessment Certificate.

Taseko Mines Ltd. contributed $137,450 to the B.C. Liberals between 2008 and 2017, while CEO Russell Hallbauer donated more than $96,000 and company chair Ronald Thiessen donated more than $64,000.

“Line their pockets and then they get protected. Why spend all this money on title and rights when you can just send money to politicians?” Jimmy Lulua asked.

Political donations by unions and corporations were banned in B.C. in 2017, after the NDP took power. Donations from individuals are also now limited to $1,200 per year.

Alphonse said the Tsilhqot’in have done the research and offered the province an escape route from the exploration permit.

Fish Lake is archeologically rich and the Mineral Tenure Act allows a permit to be withdrawn because of high archaeological potential, Alphonse said.

“If they withdraw the permit based on heritage and spiritual grounds, there is no way the company can sue them, by law. So why are they not doing it?” Alphonse asked.

A ministry spokesman said special archaeological significance was considered before the exploration permit was approved and Taseko must meet conditions to protect archaeological resources and “mitigate impacts on cultural heritage resources” including hiring a “qualified cultural heritage monitor” to do an assessment before the ground is dug up.

But in an apparent inherent contradiction in B.C.’s mining legislation, although the minister has the power to protect the area under the Mineral Tenure Act “as a mineral tenure holder, Taseko is entitled to undertake exploratory work.”

To Tsilhqot’in chiefs, it is another indication that the province is failing to act.

After winning the title and rights case, it is galling that Tsilhqot’in are being forced to risk jail by taking part in road blocks, Myers Ross said.

“I think it’s hard to believe there are not levers in government so that, if they see there’s a conflict, they could intervene. For First Nations, it seems there is still a political gap when it comes to involvement and protection of our rights,” he said.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau visited the territory last year to apologize for the unjustified hanging of Tsilhqot’in chiefs in 1864 and the federal government has stood firm on refusing to approve the mine, but B.C. Premier John Horgan has not visited the territory, even though he has the power to step in and stop an escalating situation that is likely to result in a head-on collision, Lulua said.

“John Horgan has failed to turn up at a time when our back is against the wall. He has the power to end this at the stroke of a pen, to avoid all the conflict and to (ensure) the safety of Taseko Mines and the safety of our people, but he’s sitting on the sidelines hoping it’s going to blow over,” he said.

Horgan was not available to speak on the issue.

Children from the Nemiah Valley summer school go for a swim in Konni Lake in the heart of the valley. Photo: Louis Bockner / The Narwhal

Myers Ross understands the province is in a tough position, especially as the permit is a statutory decision, meaning it is in the hands of a civil servant rather than politicians.

“(Horgan) is being told it’s a $1-billion liability, so it’s hanging over their head and they are trying to protect the public funds and not pay one cent to the company,” he said.

“But, for a company like this, that will never have our respect, it’s probably better that there should be some level of a buyout and that land should be secured for us.”

Standing on a hill, overlooking Chilko Lake, behind her Nemiah Valley home, Marilyn Baptiste wonders why Tsilhqot’in are being forced to continue fighting.

“It’s ludicrous, it’s just stupid. The company is on welfare anyway,” she said, echoing a broadly held belief that Taseko is looking to recoup money by suing if the licence is pulled and that the project is being kept on the books to keep shareholders happy.

The company’s website states that “development of this large-scale deposit would be a major step towards transforming Taseko into a strongly positioned mid-tier mining company.”

“All they have to do is … continue to raise those shares so they can continue to destroy our lands and our water,” said Baptiste, a former Xeni Gwet’in chief who was given the prestigious Goldman Environmental Award, one of the world’s largest awards for environmental activism, for her role in twice defeating the mine proposal.

Baptiste prepared submissions for the Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency in 2010 and in 2011 led a one-woman blockade to stop crews accessing the mine site. Now she fears more blockades will be needed.

Marilyn Baptiste stands on the top of Bald Mountain in the centre of the Nemiah Valley. Baptiste, who served as Xeni Gwet’in chief from 2008 to 2013, won the Goldman Environmental Prize for her work defending Teztan Biny, or Fish Lake, from Taseko Mines proposed gold and copper mine. Photo: Louis Bockner / The Narwhal

The smell of sage is strong on the wind from the valley and Baptiste wonders whether the spirits of ancestors and Mother Earth have already intervened with unexpected floods that washed out one of the main logging roads and caused a landslide on the main Fish Lake access road just as Taseko crews were preparing to enter the area.

“They are amazing washouts — I love them,” said Baptiste.

“Now you know why we fight so hard. It’s the land and the water,” she said, gazing at the expanse of pristine lakes, mountains and forests that, unlike surrounding areas, have avoided clearcuts because of the Nemiah Declaration.

The spiritual aspect of protecting the land and ensuring the water remains clean for sockeye and chinook salmon is at the root of Tsilhqot’in beliefs, said Loretta Williams, a former Xeni Gwet’in councillor, who now works for Tsilhqot’in national government.

“Mining companies are getting away with murder. There is no trust after Mount Polley. One thing we are always concerned about is the water. We take our responsibility very seriously as caretakers of the (headwaters) of the Fraser River. Aquifers go through the Fish Lake area and anything you do affects the aquifers,” Williams said.

A major problem is dinosaur provincial mining laws that have not been reformed to stop such travesties, Baptiste said.

“The Mining Act is from the beginning of time and the government is there for big industry, they are not protecting the land or protecting their constituents,” Baptiste said.

“You call this reconciliation?” she asked, predicting that, if the mine goes ahead, taxpayers will be left with huge bills for maintaining the road from Williams Lake to the mine and paying for a 125 kilometre transmission line.

“Look at who’s paying for Mount Polley. Not the company. It’s criminal,” she said.

Konni Lake stretches into the distance in the heart of the Nemiah Valley. Photo: Louis Bockner / The Narwhal

Jimmy Lulua does not disguise his contempt for the mining laws.

“The same laws that created Canada, that created B.C. and the gold rush are still here today. They have more power than a nation that has won title and rights. Why waste 29 years of legal battles and courts when you can simply get a mining permit that will give you more jurisdiction?” he asked.

“Mining laws have to be changed. It’s a new day and age.”

Consultations are underway on changes to the Mineral Tenure Act and a network of experts and environmental organizations is supporting Tsilhqot’in calls for reform.

Andrew Gage of West Coast Environmental Law Association said mining laws must be updated if B.C. wants to build a modern mining sector.

“B.C.’s gold rush-era mining laws, which give mining activity priority over virtually all other land uses, are out of touch with today’s realities,” he said.

Another source of Tsilhqot’in frustration is that the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), which could address some imbalances, has not yet been implemented.

The Tsilhqot’in Nation has submitted an urgent request for investigation to the United Nations special rapporteur on the rights of Indigenous peoples alleging an imminent violation of human rights and pointing out that the province has not implemented UNDRIP.

Jimmy Lulua believes the UN complaint will bring attention to what is happening in the Nemiah Valley.

“It’s more a shaming exercise. It educates the rest of the world on the holes in the B.C. system,” he said.

Ministry of Indigenous Relations and Reconciliation spokeswoman Sarah Plank said elements of UNDRIP have been incorporated in government programs and, this fall, B.C. will be the first province that enshrines UNDRIP into provincial law.

“The legislation will form the foundation for the province’s work on reconciliation, mandating government to bring provincial laws into harmony with the declaration over time,” Plank said in an email.

Following the Tsilhqot’in Nation’s monumental win of Aboriginal title, communities decided to reinforce traditional knowledge programs, double down on teaching the language to young people and emphasize ties to the land.

For people still recovering from residential schools and the ’60s scoop, the rights case was a boost and, now, increasing traditional knowledge is essential to facing future challenges, such as Taseko, Alphonse said.

“For a while, our people were lost, but our younger people are starting to turn more and more back to our old beliefs and our old systems. There has been a big awakening around that front and it’s important to continue to do what we can to protect those areas and protect our spirituality,” he said.

At the Yunesit’in hunting camp, the head of a deer is propped in the corner of the smokehouse while strips of deer jerky hang at the back and, outside, the ribs are slow-cooking over a fire, tended by teenagers and supervised by Merle Quilt.

“Some of them are naturals, some are a bit squeamish,” Quilt said as the uncooked meat was carved into pieces.

“It’s better than having their face buried in a device. They are learning native names for berries and trees and how to give thanks for meat and make sure there is no waste,” he said.

Winston Tallio, 17, believes learning about traditional values saved his life.

“If I didn’t connect with my culture I would have been dead at 15,” he said, noting he’d gotten into drugs.

The basis of Tsilhqot’in culture is protecting the land, Tallio said.

Winston Tallio, a youth from Anahim Lake, B.C., checks deer jerky in the smoking tent of the Yunesit’in traditional hunting camp. Tallio has returned to the land and the wisdom of elders in order to heal himself. Photo: Louis Bockner / The Narwhal

“That mountain has been here for millions of years and it will be there for millions of years. We are guardians of the land. We are not supposed to own it,” he said.

“Protect the land. It can save you or it can kill you, depending on how you treat it.”

And that protection ethos now comes with political clout that is recognized as a beacon of hope in Indigenous communities around the world, said Loretta Williams.

“It’s a battle that we carried on since 1864 when our six chiefs were hung. Since smallpox, since residential school,” she said.

“We are a healing nation. Our battles aren’t with bows and arrows any more. They are on paper, in court rooms with carefully thought out words. Our goal is to create a better future for our people, so we will press on until we achieve that. It’s not over yet.”

Taseko did not respond to calls and emails from The Narwhal.