The Narwhal picks up National Magazine Award nomination for Amber Bracken’s oilsands photojournalism

Bracken was recognized for intimate portraits of residents of Fort Chipewyan, Alta., who told her...

In a long-delayed decision, B.C.’s imperilled southern mountain caribou populations have finally been listed under the U.S. Endangered Species Act, raising hopes that the B.C. and federal governments will take action to protect the world’s only deep-snow caribou.

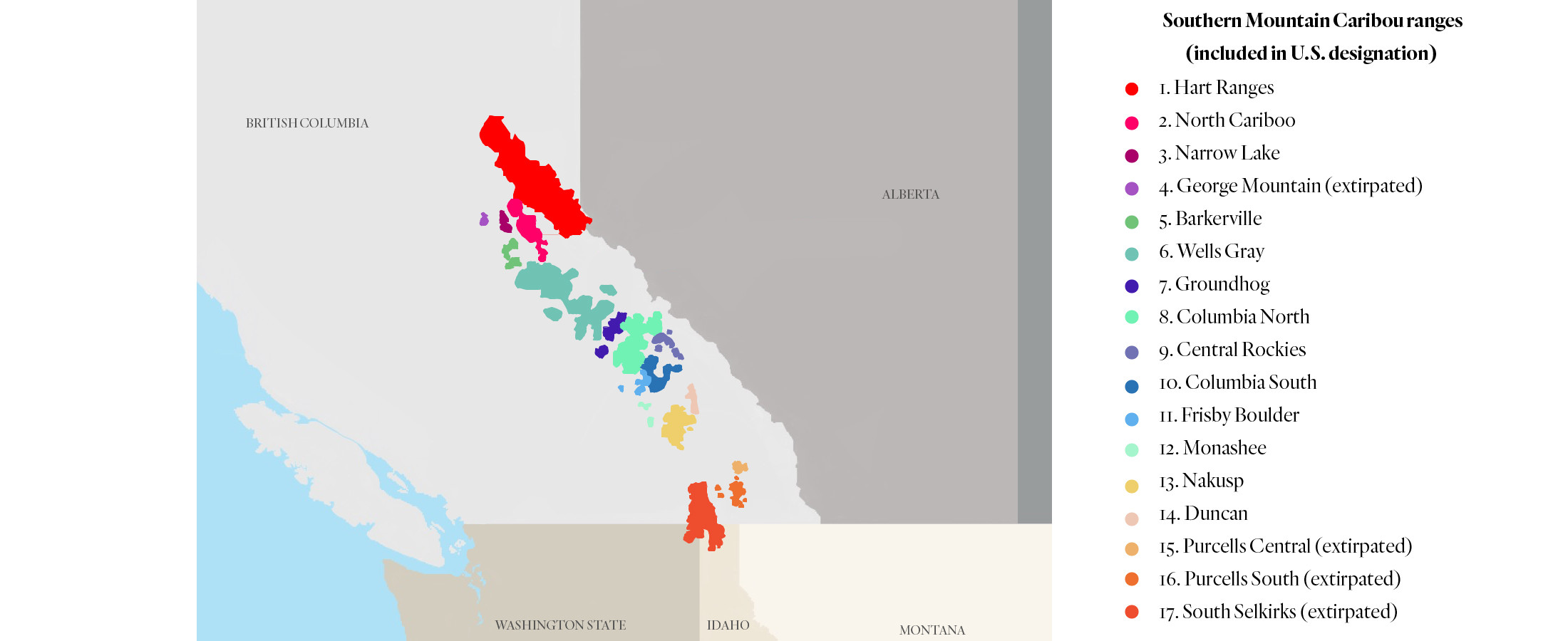

Seventeen B.C. caribou populations are included in the U.S. designation, which protects more than 12,000 hectares of critical habitat in Idaho and Washington so the species can eventually be reintroduced south of the border.

The transboundary South Selkirk herd, also known as the Gray Ghost herd, has been listed as endangered in the U.S. since 1984. That herd

this year, marking the disappearance of caribou from the contiguous United States.

The U.S. listing comes as the B.C. government issues new cutting permits to log in critical caribou habitat — including in “no-harvest” zones in designated ungulate winter range for caribou herds included in the U.S. listing — and proposes to kill more than 80 per cent of the wolf population in the habitat of three at-risk herds, including the Hart Ranges herd named in the U.S. listing.

The U.S. Endangered Species Act listing named 17 southern mountain caribou population units in B.C. that are important for the eventual reintroduction of caribou in the U.S. Caribou herds in four of the units are now extirpated. Southern mountain caribou are also endangered in other parts of B.C. Map: Carol Linnitt / The Narwhal

Ecojustice lawyer Sean Nixon said the U.S. action should increase pressure on the federal and B.C. governments to address what he called “bullshit protection” of caribou habitat and provide new incentive for the B.C. government to enact a long-promised endangered species law that appears to be stalled.

“We have this bizarre situation where there’s no caribou left in the States but they’re now protecting habitat down there so that caribou can return to the country, while we still have caribou in B.C. but the province isn’t providing any meaningful habitat protection for the species,” Nixon told The Narwhal.

“We just get these press release protections that are as flimsy as the paper they’re written on.”

In September, Doug Donaldson, B.C.’s Minister of Forests, Lands and Natural Resource Operations, told Black Press Media that additional protected areas for caribou are not needed outside the Peace region, fuelling fears that more southern mountain caribou herds will become locally extinct.

One protection often cited by the B.C. government is the designation of ungulate winter range for caribou.

But Wilderness Committee recently discovered that since 2013 the provincial government has approved 22 disturbances in “no harvest zones” in designated ungulate winter range for caribou.

While the government provided only scant details about the disturbances, they include cut blocks, drill pads and cat skiing, the latter of which extends over 1,000 hectares in ungulate winter range, according to Wilderness Committee spokesperson Charlotte Dawe.

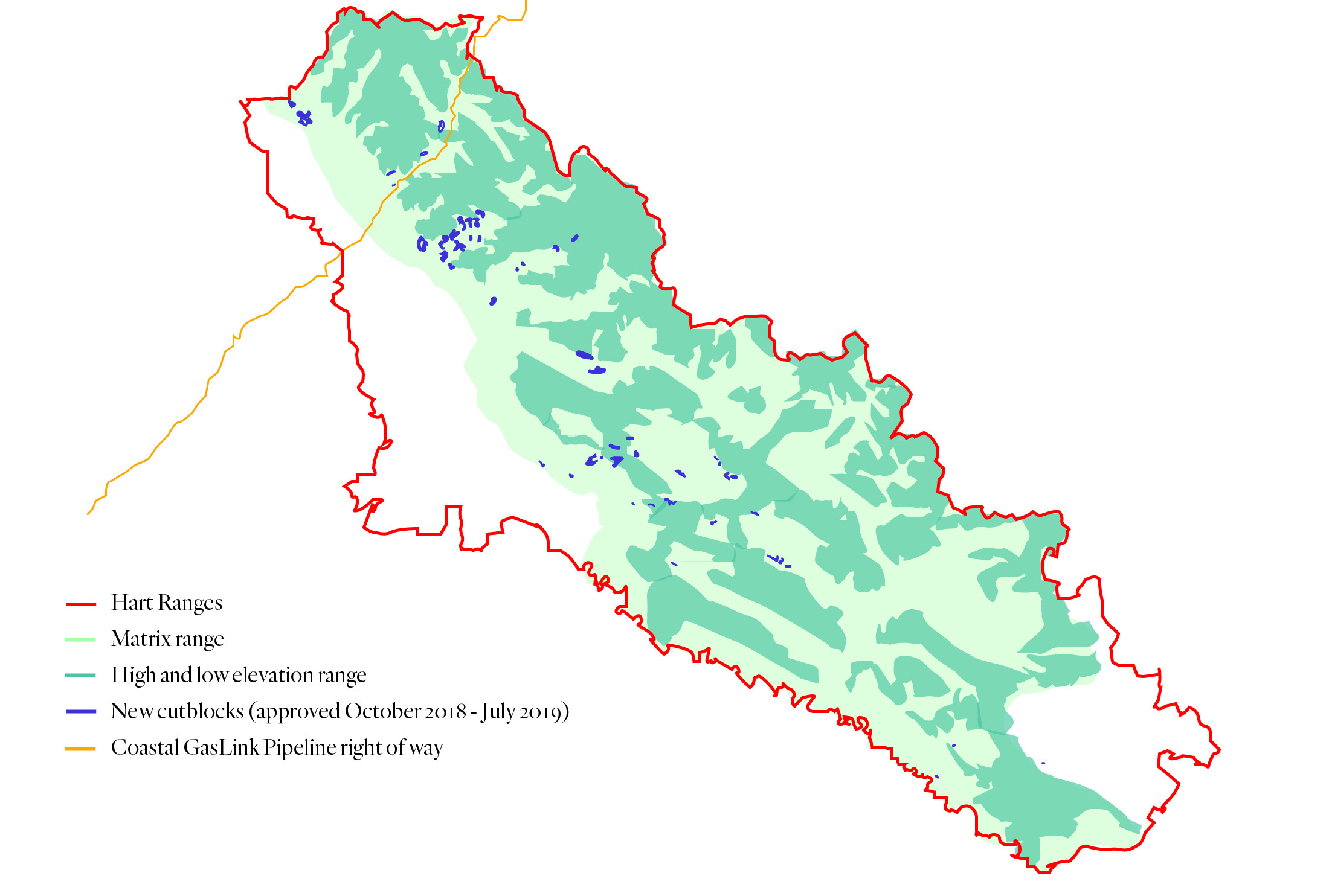

The B.C. government issued 78 cutting permits from October 2018 to July 2019 in the Hart Ranges, allowing industrial logging in 5,290 hectares, an area almost three times the size of the city of Victoria. The Hart Ranges caribou were named in the U.S. listing. Map: Carol Linnitt / The Narwhal

“Companies, government and industries are still able to cause disturbances within ungulate winter range,” said Dawe, the committee’s conservation and policy campaigner.

“What they say is totally protected and set aside is not true.”

Flagging tape marks the route of TransCanada’s Coastal GasLink pipeline, which cuts a wide swath through critical habitat for the endangered Hart Ranges caribou herd in the Anzac River drainage. Photo: Taylor Roades / The Narwhal

The southeast Kootenays, whose caribou herds are included in the U.S. endangered species listing, is one of the areas with the greatest number of disturbances in “no harvest” zones, Dawe noted.

Ungulate winter range designations for caribou also contain “conditional” harvest zones where forestry companies can apply for exemptions for logging and other disturbances, Dawe said.

When the Wilderness Committee and Wildlife Defence League recently examined disturbances in “conditional” harvest zones in the core critical habitat of the Wells Gray caribou herd, also included in the U.S. designation, they found the equivalent of more than 500 CFL football fields had been logged since April.

“They’re doing anything they can to avoid habitat protection,” Dawe said. “It [ungulate winter range] opened up a lot of room to be able to go in and log … It makes it pretty well open for business.”

B.C. approves 314 new cutblocks in endangered caribou habitat over last five months

Human disturbances, including clear-cut logging, mining and oil and gas development, have given natural predators like wolves easy access to caribou whose habitat has been destroyed or fragmented across Canada, with disastrous consequences for once-robust herds.

Almost 30 of B.C.’s 52 surviving caribou herds are at risk of local extinction, and a dozen of those herds now have fewer than 25 animals.

Along with the South Selkirk herd, the South Purcell herd in the Kootenay region was declared functionally extinct in January. The few remaining survivors from both herds were captured, tranquilized, and transported by truck and helicopter to a pen, where they were held with an orphan caribou calf named Grace and later released to join the endangered Columbia North herd.

Upon relocation, survivors from the South Selkirk and South Purcell herds rouse from sedation to find Grace, a curious youngster. Grace, born in a maternity pen for endangered caribou, became the sole remaining member of the Revelstoke herd after her mother was killed by wolves. Photo: B.C. Ministry of Forests, Lands and Natural Resource Operations

Scientist Chris Johnson said there is already a significant amount of pressure on both the B.C. and federal governments to do more to protect the iconic species engraved on the Canadian quarter.

The U.S. decision may finally prod the federal government to list southern mountain caribou as endangered under Canada’s Species at Risk Act, as recommended five years ago by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC), Johnson said.

Southern mountain caribou are listed as threatened under Canada’s Species at Risk Act (SARA). They are red-listed, or endangered, in B.C.

But shifting the federal status of caribou from threatened to endangered is unlikely to make much of a difference in terms of protection measures, said Johnson, an ecology professor at the University of Northern B.C. who sits on committees advising the federal government on caribou recovery.

“There’s been a lot of foot-dragging,” he said in an interview.

“I’m not convinced that endangered status, from threatened, is really going to change a lot. Under SARA, threatened or endangered species basically have the same requirements for action and most of those timelines have been missed by the federal and provincial governments.”

Last May, federal Environment Minister Catherine McKenna declared that southern mountain caribou face “imminent threats” to their recovery and said immediate intervention was required.

B.C. subsequently announced two draft agreements aimed at protecting caribou and two further years of consultations.

If McKenna is not satisfied that B.C. has a suitable plan of action to protect endangered herds, she can ask the federal cabinet to approve an emergency protection order under the federal Species at Risk Act. That would allow Ottawa to make decisions that are normally within the jurisdiction of the B.C. government, such as whether or not to grant logging permits.

The U.S. listing arose following a lawsuit launched earlier this year by the Center for Biological Diversity after the U.S. government failed to act on a 2015 court ruling that ordered the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to designate critical habitat for mountain caribou.

Andrea Santarsiere, a senior attorney at the centre, said normally a designation would occur within a year of a court ruling.

“They had seemed to kind of stall,” she said in an interview. “So we filed a lawsuit just asking them to move forward and finalize their designation.”

Santarsiere said the designation recognizes the South Selkirk herd moved back and forth between the U.S. and Canada and that B.C. still has 15 deep-snow caribou herds which could be important for the reintroduction of the species in the U.S.

“I think that will force the governments to work together and come up with a plan that protects habitat so caribou can potentially return to the lower 48 states again at some point in the future.”

She said the news earlier this year that the transboundary South Selkirk herd was functionally extinct was surprising to some Americans and saddened them.

‘We have left it too late’: scientists say some B.C. endangered species can’t be saved

“A lot of people that had followed the plight of the caribou were really disappointed. And a lot of people who knew nothing about it heard it for the first time and thought ‘wow, why didn’t we do more to protect them when they were here?’ ”

Santarsiere said the designated critical habitat in the U.S. in northwestern Idaho and northeastern Washington is not nearly as much as the centre had hoped for, noting that 150,000 hectares were originally proposed for protection.

“This was just a very miniscule amount compared to what was originally proposed, and I think it’s insufficient,” she said.

“Existing tools are what’s led, and is continuing to lead, to the extinction of B.C. species.”

“Certainly, caribou cannot and will not return to the lower 48 states without help from the British Columbia government to protect the habitat in British Columbia. And this is where we hope that the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the British Columbia government can work together to come up with a recovery plan that really does protect habitat.”

A listing under the U.S. Endangered Species Act, widely viewed as a global gold standard for species protection, provides a program for the conservation of the species and its habitat.

In the absence of endangered species legislation in B.C., Nixon said the province has no legal duty under existing law to protect the habitat caribou need for their survival.

“Existing tools are what’s led, and is continuing to lead, to the extinction of B.C. species.”

The U.S. legislation should get attention from high levels in the B.C. government and put political pressure on “from the top down that will hopefully lead to B.C. actually doing something to protect the only remaining mountain caribou left in the world,” Nixon said.

B.C.’s Environment Ministry referred questions about the caribou listing and endangered species legislation to the Ministry of Forests, Lands and Natural Resource Operations. In an emailed response to The Narwhal, the forests ministry said “the designation in the U.S. does not impact British Columbia.” The ministry said it has no further comment at this time.

‘Deliberate extinction’: extensive clear-cuts, gas pipeline approved in endangered caribou habitat

The federal environment ministry said in an email that it is aware of the U.S. designation, noting it is consistent with COSEWIC’s 2014 assessment of southern mountain caribou and that, under SARA, species listed as threatened and endangered receive the same treatment.

“Canada and U.S. officials are meeting regularly through different forums to discuss matters of common interest related to wildlife conservation,” the ministry said.

The provincial government recently completed a 30-day consultation with Indigenous communities and other ‘stakeholders’ to discuss a proposed two-year predator cull in the habitat of three at-risk southern mountain caribou herds.

They include the Hart Ranges herd, in whose critical habitat the B.C. government issued 78 cutting permits from October 2018 to July 2019, allowing industrial logging in 5,290 hectares, an area almost three times the size of the city of Victoria.

A clear-cut in the Anzac River drainage, making way for the Coastal GasLink pipeline to supply LNG Canada with fracked gas from B.C.’s northeast. The pipeline will impact three endangered caribou herds, including the Hart Ranges populations. TransCanada, which is building the pipeline, says it will have a “useful life” of 30 years. Photo: Taylor Roades / The Narwhal

A memo signed by Darcy Peel, director of B.C.’s caribou recovery program, says more than 80 per cent of the wolves in the habitat of the three herds must be eliminated in order to reverse caribou declines.

In preparation for the proposed wolf cull, the B.C. government is asking hunters not to shoot wolves with GPS radio collars as it considers shooting packs from helicopters in a last-ditch attempt to save the herds.

In a memo to hunters, Donaldson’s ministry says it has deployed radio collars on wolves to more easily locate packs for “aerial wolf reduction,” noting that more than 80 per cent of wolves in the range of the three herds in central B.C. must be killed to reverse caribou population declines.

“When collared wolves are removed from their pack, the capability to reduce wolf numbers is significantly diminished, as packs can no longer be located quickly and efficiently reduced,” said the document, a copy of which was shared with The Narwhal.

“The more collared wolves alive on the landscape, the more effective wolf pack reduction will be.”

The document explains that collaring wolves is time-consuming and expensive, using the example of capturing and collaring wolves on the Chilcotin Plateau last winter, when it took 12 days to capture 21 wolves in 10 packs and the average cost of capturing and collaring each wolf was $9,400.

“We ask that hunters and trappers be aware of collared wolf packs in your area and consider the implications of removing radio-collared wolves from the wolf population … If you do harvest a collared wolf, please return collars to your local government office.”

Johnson and other scientists say that measures such as wolf culls and maternal penning, in which pregnant caribou cows are captured and penned until their calves are old enough to stand a chance of escaping predators, will only save caribou herds from local extinction if sufficient habitat protections are also in place.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. Angello Johnson’s shoulders burn, and his arms...

Continue reading

Bracken was recognized for intimate portraits of residents of Fort Chipewyan, Alta., who told her...

A guide to the BC Energy Regulator: what it is, what it does and why...

The B.C. government has introduced legislation to fast track wind projects and the North Coast...