‘Afraid of the water’? Life in a city that dumps billions of litres of raw sewage into lakes and rivers

10 billion litres of sewage are dumped into Winnipeg’s lakes and rivers each year. Some...

This photo essay was made possible through the generous donations of 94 readers. The Narwhal is a non-profit online magazine dedicated to publishing stories about Canada’s natural world you can’t find anywhere else. You can donate here to support our independent journalism. Every bit counts.

There are only a handful of ways to get into the roadless wilderness of the upper Taku River.

You can take an onerous 100-kilometre jetboat ride up the river from Juneau, Alaska’s capital city, or you can come in from the air, either by helicopter charter or by bush plane, which will land you in a lake where you can join the flow downstream.

The wildness and vulnerability of the Taku are what have drawn me and my good friend Alex Craven to undertake a 130-kilometre pack-raft trip from a headwater lake nearly to its confluence with the Pacific.

Alex Craven surveying the abandoned Tulsequah Chief mine site after a 15-kilometre hike up the river bed. Photo: Colin Arisman / The Narwhal

Besides a few short 4×4 trails, the entire Taku watershed remains without access roads and is considered to be the largest intact wilderness river system on the Pacific Coast of North America, despite past mineral development in the valley.

As an avid fly fishermen and back-country traveller in Alaska, I’ve wanted to visit the Taku for years because of its jaw-dropping beauty and relative isolation. Despite abundant wildlife including grizzlies, caribou, wolves, moose and all five species of salmon, the remote region sees few visitors.

But there’s another reason for my interest in the Taku.

As a photographer and journalist, I’m also here to document the abandoned Tulsequah Chief mine which, since the 1950s, has leaked acid mine drainage into a tributary of the Taku, the prevailing salmon-producing river for southeast Alaska.

Despite mounting public pressure, the Canadian and British Columbian governments have failed to clean up the mess for more than 60 years.

The Tulsequah Chief mine is frequently referenced by downstream Alaskan stakeholders, tribes and fishermen as evidence B.C. cannot responsibly regulate the mining boom taking place near transboundary rivers that flow between Canada and the U.S.

Arriving at the floatplane, Alex, a skilled paddler and staffer with the Sierra Club based out of Seattle, hops in the front seat.

Alex Craven gazes out across millions of hectares of roadless, unfragmented wild country. Photo: Colin Arisman / The Narwhal

Moving inland from the wet coastal range of Alaska, the Taku Valley forests transition from temperate rainforest to boreal forest in the drier interior of British Columbia. Photo: Colin Arisman / The Narwhal

Juneau slips out of view as we bank away from the Pacific and into the mouth of the mighty Taku River.

The fishing boats scattered across the confluence below us — where millions of salmon are beginning their arduous journey home to headwaters — disappear from view as we move toward the wide-open valley ahead. Tall peaks tower on either side, as the vast 1.8 million-hectare Taku watershed opens up in front of us. This will be our home for the next seven days.

We float the Inklin River to its confluence with the Nakina where the Taku River begins on the map. Photo: Colin Arisman / The Narwhal

The location of the abandoned Tulsequah Chief mine in relation to the vast 1.8 million-hectare Taku River watershed. Map: Carol Linnitt / The Narwhal

Our travel route included an eight-kilometre hike from King Salmon Lake to the Inklin River. Once on the river, we paddled downstream to join the Taku River and eventually took a detour north to the Tulsequah River where we located the abandoned mine site. Map: Carol Linnitt / The Narwhal

After an hour-long bush flight, the plane circles and lands on a large mountain lake.

We grab our packs and begin the eight-kilometre hike down to the Inklin River, a tributary of the Taku.

Alex Craven shuttling a heavy pack loaded with pack rafts, life jackets, cameras, bear spray, camping gear and a week’s worth of food from our float plane on King Salmon Lake. Photo: Colin Arisman / The Narwhal

Hiking down to the river requires fighting chest-high thickets of devil’s club and swarms of mosquitoes. Photo: Colin Arisman / The Narwhal

We are grateful to find an old trail that runs along a trapline but in places it has been completely reclaimed by the forest and soon we are bushwhacking. Blindly pushing through the thick undergrowth, we know we could easily bump into a bear or moose.

The mosquitoes swarm.

Thick devil’s club, a fierce spiny plant, makes for slow progress. It’s four hours until we hear the sound of the Inklin

.

Finally at the river’s edge, we inflate pack rafts, load our gear and begin the seven-day float.

Alex paddles his inflatable pack raft down the Inklin River. Photo: Colin Arisman / The Narwhal

Though the wilderness is rugged, the weather is fair and calm. We make our way through the rapids of the Inklin Canyon and into the swift but gentle current that will be the norm for the rest of the paddle.

The Taku River runs near the 58th parallel. As our float coincides with the summer solstice, the sun barely sets at midnight during a short interval of bright evening twilight.

Our first night we camp next to a clear stream and catch a nice Dolly Varden, a species of char that splits its time between the ocean and pristine rivers like the Taku.

Dolly Varden are an anadromous species of trout that gather in large numbers in the Taku River to feed on the salmon spawn. Photo: Colin Arisman / The Narwhal

Tiger swallowtail gathering is a sign of the return of chinook salmon, called king salmon in Alaska. While the Taku River has historically been known for bountiful returns of kings, numbers have been declining in recent years resulting in closures to the fishery. Photo: Colin Arisman / The Narwhal

We’re travelling through a part of the four million hectare (10-million acre) traditional territory of the Taku River Tlingit First Nation.

Less than 200 years ago the river was flanked by permanent village sites and seasonal subsistence camps. To this day the Taku River Tlingit people rely on the river and watershed for moose, deer, caribou and prized chinook salmon.

Several decades ago, the First Nation successfully fought the proposed development of a 159-kilometre access road that would have crossed the heart of the watershed, opening it up for mineral exploration.

In 2011, the nation and provincial government agreed to protect a large part of the watershed from development and to jointly manage aspects of the region.

But that agreement has done little to remedy the decades-old problem of the Tulsequah Chief mine, situated on the Tulsequah River, a major tributary of the Taku.

A view of the midnight sunset from our camp on the Taku River. Photo: Colin Arisman / The Narwhal

Alex cooks a fish dinner over the campfire. Photo: Colin Arisman / The Narwhal

Paddling up to the staging area for the Tulsequah Chief mine. From here we hike 15 kilometres up a dirt road along the bank of the Tulsequah River to the abandoned mine site. Photo: Colin Arisman / The Narwhal

A small rotting dock is the first sign we see of the abandoned Tulsequah Chief mine. We pull our rafts up and step on the bank. This is the spot where barges would land after a long, perilous run up the swift, shallow Taku River. From here trucks would transport equipment up the 15-kilometre provisional road to the mine.

Discarded trucks and boats, bunk houses and storage containers are scattered around the yard, left to rust amongst the trees.

In Canada it is not uncommon for mining companies to walk away from cleanup obligations. According to a July report from Canada’s Ecofiscal Commission, “as many as 10,000 orphaned and abandoned mine sites exist across the country.” The report notes that, “B.C.’s policies have contributed to a situation where, according to the most recent figures, the province holds only $1.36 billion in financial assurance against an estimated $2.8 billion total cleanup liability.”

Skiffs and barges were used to run workers and materials upriver to this staging area, from which trucks could drive the access road to the Tulsequah Chief mine. Photo: Colin Arisman / The Narwhal

After five days on the river, the sight of rusting and discarded 50-gallon drums of chemicals feels strikingly out of place. Their mere existence here — 100 kilometres into the backcountry, in a vast roadless landscape — feels implausible.

As we walk around, we see the remnants of several stages of ownership and haphazard operation of the site. Since Teck-Cominco abandoned the site in 1957, two companies — Redfern Resources and Chieftain Metals — have obtained exploration permits by promising to clean up the acid mine drainage.

Both failed in their cleanup efforts and collapsed under debt.

We wondered whether the skull and crossbones on the outside was meant as humour or a legitimate health warning. Standing near the door, I was quickly struck with a headache. Photo: Colin Arisman / The Narwhal

An abandoned silo at the staging area is filled with trash, chemical waste and discarded equipment. Photo: Colin Arisman / The Narwhal

Road building is a topic of intense debate in southeast Alaska where there are no major road systems connecting the region’s communities. Photo: Colin Arisman / The Narwhal

A bunkhouse, still appearing new, looked as though it had been abandoned in a hurry, soon after construction. Shoes, telephones and other supplies lay in piles on the floor. Photo: Colin Arisman / The Narwhal

An abandoned room in the bunkhouse. Photo: Colin Arisman / The Narwhal

From the staging area we spent a day hiking up the access road and then the riverbed to the site of the Tulsequah Chief mine.

Situated directly on the bank of the river, the site was startling and apocalyptic.

Several new buildings, numerous storage containers and treatment ponds were scattered along the riverside. Rising steeply up from the river was a hillside that had been torn up by mining work.

The Tulsequah Chief mine site situated just metres from the river. Photo: Colin Arisman / The Narwhal

There were several pallets of ferric chloride, used in water treatment. Crisscrossing a dried up tailings pond, black bear tracks were perfectly preserved in the orange mud. The door of a storage container was cracked open, a pile of ominous-looking soak rags in a heap.

A large shed was filled with what appeared to be materials for an elaborate water treatment system. The water treatment system looked as if it was in very new condition and perhaps never operated before abandonment.

Numerous containers are filled with chemicals and equipment from attempted cleanup of the mine site. Photo: Colin Arisman / The Narwhal

A barrel of ferric chloride. Photo: Colin Arisman / The Narwhal

The hill above the river has been excavated extensively and the open earth is stained with the signature rust colour of acid mine drainage. Few plants grow among the orange rocks and many trees appear dead or dying. Several creeks run down through the old mine waste into a pond coated in a thick orange slime.

Previous owners of the site were required to construct new wastewater treatment systems but it’s clear standing near the river’s edge how thoroughly those attempts have failed. A wastewater pond, separated from the river by just 10 metres of gravel bank, has breached and eroded. A small stream of contaminated water flows directly into the Tulsequah.

The overflowing containment pond. Photo: Colin Arisman / The Narwhal

The wall separating the pond from the Tulsequah River has eroded and wastewater now drains directly into the river. Photo: Colin Arisman / The Narwhal

Over the last decade Canadian officials have at times alleged that “there there isn’t significant environmental harm being done” to the watershed by the water leaking out of Tulsequah Chief. However, this summer the commissioners of several Alaskan agencies wrote that “there are measurable impacts to Tulsequah River water quality and fish habitats next to the mine site and a mile and a half downstream in the Canadian portion of the river.” They noted that these impacts have not yet been detected on the Alaska side of the Taku.

The Canada-U.S. border is marked by a clearcut strip, which cuts across the Taku valley about 20 kilometres from the mine site. Photo: Colin Arisman / The Narwhal

Pressure on B.C. increased in June with a letter from eight senators to Premier John Horgan, urging him to address the threats to transboundary rivers from mining.

“As you know, Alaska, Washington, Idaho and Montana have tremendous natural resources that need to be protected against impacts from B.C. hard rock and coal-mining activities near the headwaters of shared rivers, many of which support environmentally and economically significant salmon populations,” the senators wrote to Horgan.

“These transboundary watersheds support critical water supply, recreation opportunities and wildlife habitat that support many livelihoods in local communities.”

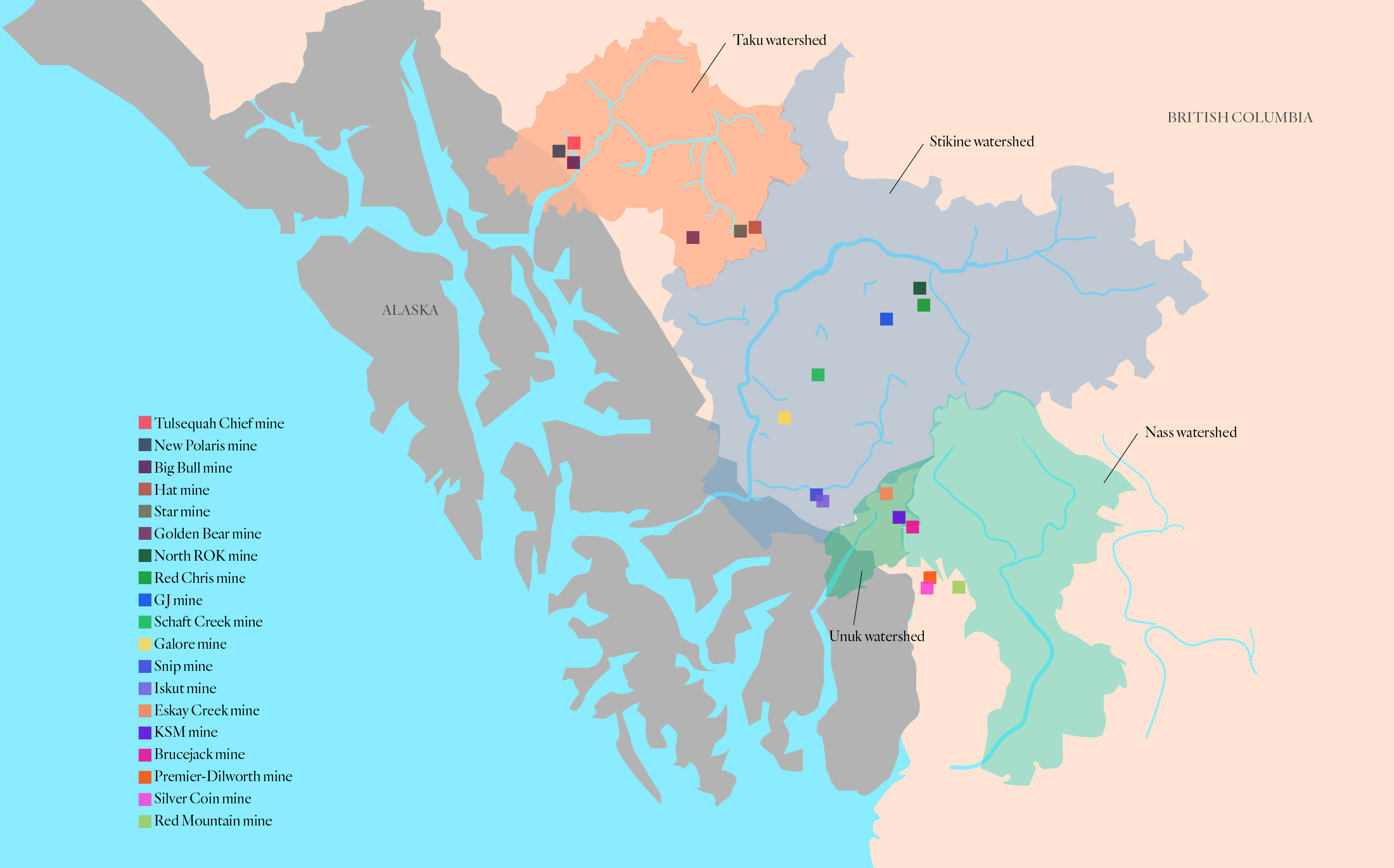

There are numerous mines at various stages of their lifecycle from proposed to active to abandoned in the B.C.-Alaska transboundary region. Mapped above are 19 of those mines spanning four major river watersheds, including the Taku, the Stikine, the Nass and the Unuk, all of which support major salmon populations. Map: Carol Linnitt / The Narwhal

The letter followed a report from the University of Victoria’s Environmental Law Centre that found 1,100 closed mines across B.C. that continue to represent environmental threats.

The report found that some mines subject to acid mine drainage can never be fully cleaned up and may be subject to expensive water treatment in perpetuity. The Britannia mine, for example, required a $46 million treatment system for acid drainage that requires $3 million each year to operate — all funded by taxpayers.

A coalition of 30 groups in B.C. this summer called on the province to overhaul out-dated mining laws to alleviate risks to the public and the environment.

Alex’s souvenir from the trip was a beautiful moose shed. Photo: Colin Arisman / The Narwhal

Desire for a solution to the Tulsequah Chief mine is at an all-time high with multiple new mine projects in various stages of proposal or development along the B.C.-Alaska border.

But there’s also cautious optimism for the Tulsequah River now that B.C. has finally selected a contractor to develop a cleanup plan. However, the contractor — embattled SNC Lavalin — is steeped in controversy and an unfolding ethics scandal that could once again derail cleanup of the site.

A final remediation plan is not expected until the end of 2019.

The Tulsequah Chief gives some indication of how costly and challenging a long-term containment and treatment solution is, even for a small amount of waste water.

New mines in the transboundary watershed are being built at a scale far greater than the Tulsequah Chief.

Several years ago I flew over the Red Chris mine, owned and operated by Imperial Metals, a company facing the threat of bankruptcy. I was awestruck by the scale of the mine and tailings pond after only two years of production. Red Chris is perched on a mountain top above the Stikine River watershed, another salmon-rich transboundary system shared by B.C. and Alaska.

Imperial Metals’ Red Chris mine in the headwaters of the Stikine River. Photo: Colin Arisman / The Narwhal

Imperial Metals is also the company that owned and operated the Mount Polley mine, the site of one of Canada’s largest environmental disasters after a tailings pond collapsed, sending 24 million cubic metres of contaminated water into Quesnel Lake.

Imperial Metals’ full reclamation costs are estimated at $173.6 million, with only $14.3 million held in reclamation deposits.

The Taku Glacier near the confluence with the Pacific Ocean where we caught a flight back to Juneau from a lodge. Photo: Colin Arisman / The Narwhal

Photo: Colin Arisman / The Narwhal

As we paddle out past the melting Taku glacier and to the confluence where salt and freshwater meet, I try and wrap my head around the timescale of water, rock and ice.

A salmon jumps and makes a daring dash across the water’s surface. A moment later a seal head pops up just five metres from our boat, a sockeye dangling from its mouth. It is the magic of moments like this that have led me to fall in love with southeast Alaska.

These are also the moments that highlight what is at stake as B.C. considers new and larger mines in these remote, shared regions.

*Article updated on Oct. 11, 2019, at 2:45 p.m. to reflect the fact that both Chieftain and Redfern went bankrupt and to correct a previous reference to strip-mining on a hillside. The mining was actually underground mining, not strip mining.