Bill 15: this ‘blank cheque’ legislation could dramatically change how B.C. approves major projects

Premier David Eby says new legislation won’t degrade environmental protections or Indigenous Rights. Critics warn...

On a cold day in November 1989, my father was flying low in a Cessna-185 fixed-wing airplane over the Caribou Mountains in northern Alberta, when he saw a vast number of otherworldly animals scattered across the surface of a frozen lake. He was astonished. He called them grey ghosts.

The Caribou Mountains — more wetlands than mountains — rest on a saucer-shaped plateau gently ascending above the surrounding lowlands of the Peace River valley, blanketed in sphagnum moss, bog cranberry, Labrador tea and lichen. It’s a vast tract of 13,405 square kilometres of subarctic boreal forest bordering the western boundary of Wood Buffalo National Park. The land is pockmarked with what are known as collapse scar bogs, depressions where thawing permafrost created slumped bogs pooling with water.

Few species can survive on such a harsh landscape, but it’s home to what my dad calls the grey ghosts: threatened boreal woodland caribou. Their wide hooves — “like snowshoes,” my father says — help buoy them above the snow, while acting like shovels to scoop and paw to forage through the winter. Caribou’s specialized digestive systems allow them to glean sugars and nutrients from 100-year-old lichens. They’re so hardwired to lichen they can scent it entombed beneath three to four feet of ice and heavy snow.

Woodland caribou diverged from barren ground caribou more than 350,000 years ago. While their strategy has always been to make themselves scarce — “to spread out on the landscape in low-density herds,” my father says — today they are in grave peril. Herds have disappeared. Although uncertain of their historic numbers, biologists have documented declines as early as the 1970s. Only 2,000 caribou remain in Alberta today.

My father — Dave Moyles, then a wildlife biologist with the government of Alberta — and his colleagues had craned their necks straight down, as the snow-covered landscape slid by, their eyes searching open stands of black spruce. That day, they were looking for moose, although my dad spent much of his career searching for caribou.

He was astounded, on that day, to count 80, 90 and then 100 woodland caribou. They couldn’t sum up an exact ratio of females to males to calves — a standard measurement — because “there were way too many animals,” my father recalls. It was likely what’s known as a post-rut aggregation, he tells me, a term to describe when woodland caribou come together in October to mingle and mate, the males knocking antlers in combat over small harems of females.

The size of the herd echoed the oral traditions told by the Little Red River Cree Nation who hunt and trap in the Caribou Mountains, my father says. Hunters had told him stories about seeing massive herds of woodland caribou on the west end of Margaret Lake, the source of the Pontoon River, located northwest of Fort Vermillion, Alta.

“I’d never see anything like it again,” my dad says now. “What we saw [over the years] was mostly declines. You couldn’t find caribou in places where you used to find caribou.”

My father has now flown over the changing landscape in Alberta for 30 years. Cumulative pressures on woodland caribou have never been higher. The federal Species At Risk Act states 65 per cent undisturbed forest in a caribou range offers a 60 per cent chance of a herd maintaining a self-sustaining status, meaning it can survive without conservation efforts. But most of Alberta’s herds are already facing losses far below that threshold. There are no self-sustaining herds left in the province — remaining populations are maintained by controversial, government-funded wolf cull programs.

“You can visualize the health of a range by looking at the amount of area impacted by humans,” my father says. “Cut lines, well sites, roads, seismic lines, cutblocks — and also how much forest has been burned by wildfires in the last 40 years.”

Unprecedented and devastating wildfire seasons in recent years have undoubtedly factored into the equation, and the future of woodland caribou in Alberta has never been more uncertain. In 2023, a record-breaking 3.3 million hectares burned — nearly seven per cent of the province’s forests — disturbing more land than the 11 previous fire seasons combined. A recent report by the Alberta Biodiversity Monitoring Institute found woodland caribou lost more than five per cent of critical habitat to wildfires in 2023, with northern herds facing the most severe losses, including nearly 13 per cent in Bistcho Lake range and nearly 14 per cent in the Caribou Mountains.

The 2024 season has only intensified the crisis for woodland caribou in Alberta. By mid-August, there were more than 100 wildfires burning in Alberta with the largest, the Semo Complex, burning 15 kilometres north of Fox Lake, right in the way of caribou habitat in the Caribou Mountains. At more than 100,00 hectares, it’s nearly twice the size of Edmonton. The Melvin River Complex, at roughly the same size, is burning on the northeast and southeast side of Bistcho Lake, which is home to the Bistcho caribou herd.

Wildfires are burning at a higher frequency and severity than decades past, experts say. The time interval between major fire events — what scientists call “stand-replacing” fires — is shrinking. What does that mean for a species adapted for survival in old-growth forest — forests at least 40 to 50 years old? Can the grey ghosts survive the intensifying wildfire crisis?

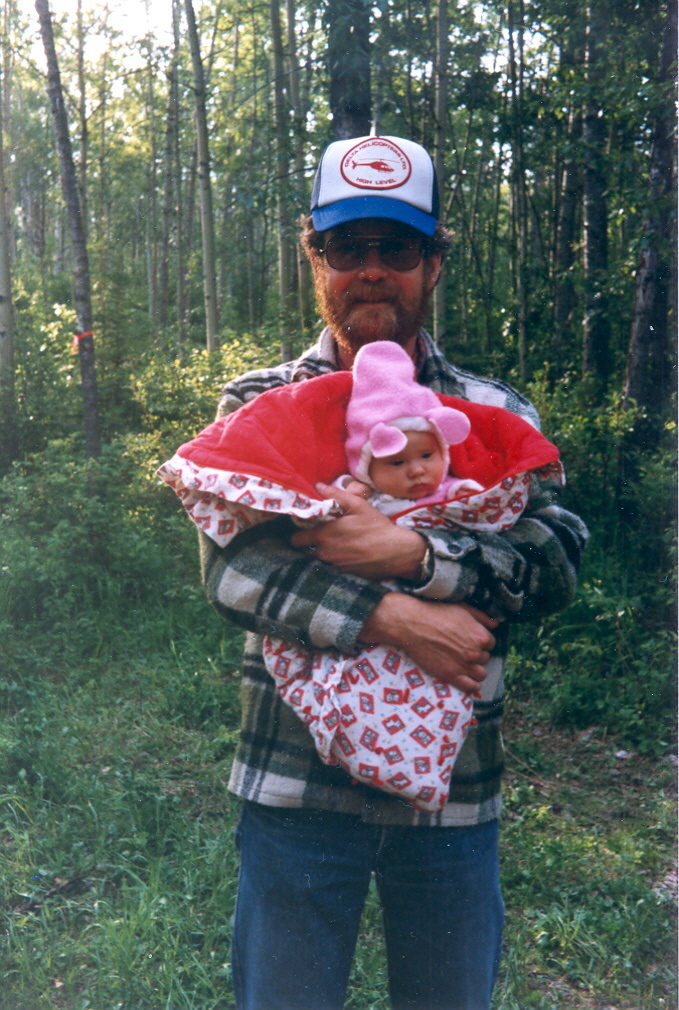

I was only four years old when my family moved to Peace River, Alta., and my father began flying over the boreal forest in the northwest corner of the province, counting caribou. Every February, from 1989 to 2017, he listened to the pulse of caribou, the females outfitted with radio collars, documenting their diminishing herds. He counted the number of calves born and compared that number to the number of females lost, every year, to measure what was called the “recruitment survival index.”

Over the latter half of the last century, woodland caribou populations in Canada have suffered steady losses due to the encroachment of extractive industries. In 2002, the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada designated woodland caribou as “threatened” and, in 2003, the federal Species At Risk Act followed with the same designation. Today, many of the 15 remaining herds in Alberta are on the verge of extirpation, or local extinction. Some herds have seen their population drop by close to 80 per cent.

The causes of their plight have been well documented. Caribou are arguably one of the most studied wildlife species in Alberta. Human disturbance through the industrial development of oil, gas, timber and peat has resulted in loss and fragmentation of caribou habitat. Disturbance of old-growth forest encourages the growth of pioneer species, or the first species to colonize landscapes altered by industry, including grasses and leafy shrubs and trees. This attracts foraging deer and moose and, in turn, more predators. Linear features become highways for wolves and bears to more easily prey on caribou.

Historically, the fire cycle in the Western boreal forest burned every 100 to 150 years, so woodland caribou evolved to live closely with wildfire. Like caribou, fire belongs in the boreal forest. It has a role to play: releasing coniferous seeds, stimulating the growth of pioneer species and regenerating the cycle anew. Over tens of thousands of years, fire has shaped caribou.

My father recalls the summer of 1995 when a lightning-caused wildfire swept through the Caribou Mountains, candling in the black spruce and smouldering deep in the lichen-carpeted peat, growing to cover 129,000 hectares.

Researchers estimated it was the first time the forest had burned in over 90 years. In 1998, another large-scale wildfire tore across the boggy plateau. Researchers at the University of Alberta calculated 76 per cent of the caribou’s home range was razed by the 90s fires.

“The 1990s saw some bad fire years in the Caribou Mountains,” my dad says. “There were these peat pockets along the Pontoon River. You could actually see the depth — 100 feet deep in some places — but the fires were so hot and extensive that a lot of that burnt right off.”

Woodland caribou aren’t helpless in the face of fire. My father hypothesizes they’ve learned to avoid and flee from wildfires based on at least three adaptive traits. First, their acute sense of smell can likely pick up the scent of wildfire smoke, pushed by the winds. Second, their bodies are designed for long-distance travel. And third, like us, they possess an intricate memory of the landscape. They somehow know where to go.

“Caribou just keep moving, moving, moving,” my father says. “It wouldn’t be unheard of for them to travel 20, 30 kilometres in a day. And as long as some of the herd know of these pockets of [habitat] they’ll keep seeking them out.”

This is what my dad calls herd memory: knowledge passed down from female caribou to her offspring like an old, weathered map of the land — a family heirloom of sorts. It’s why the loss of even one female can be so detrimental to a small herd, he says.

The winter after the wildfire in 1995, my dad flew over the Caribou Mountains and saw caribou travelling through the residual remains of the burn, what firefighters call “the black.” Wildfires don’t typically raze the forest down to ashes in a uniform fashion. They often leave behind pockets of trees, understory and patches of lichen, somehow unscathed.

“A caribou is so sensitive they’ll pick up the unburned lichen through the snow,” my dad says. “You’d see them feeding in an area for, say, a year or two following a burn.”

But beyond that, he saw that caribou avoid the charred forest entirely.

Some wildfires are beneficial to wildlife species in the boreal forest, ushering in scores of insects to burrow in blackened trees. Fire beetles can sense the heat from kilometres away and scuttle toward the ashes to breed and lay eggs. Birds and bats descend on the swarms of insects. Black-backed woodpeckers prefer to hammer nests into charred trees — it’s believed their habitat will grow by nearly 13 per cent as a result of the 2023 wildfires. Pioneer plants and grasses rise from the nitrogen-rich soil and attract mule deer, white-tailed deer and moose, while predator species, including wolves and bears, stalk their footsteps.

Wildfire isn’t inherently bad for caribou. A recent study indicates that, after 20 years, lichens regenerated faster in areas disturbed by wildfire compared to areas that were clear cut for timber. The study’s author, Ian Best, a post-doctoral biologist at the University of Northern British Columbia, isn’t entirely sure why, but posits it could be because fire leaves pockets of unburnt lichen behind, or the result of charred deadfall and coarse woody debris suppressing the growth of leafy plants, which tend to outcompete lichen.

But indirectly, wildfires open up access to the landscape and caribou habitat. My father observed how, following the fires, wolves could “work an area” through the open burn. And it wasn’t only the wolves. Once, he responded to the collar on a female caribou that had gone into “mortality mode” — a rapid-firing radio frequency — in the Caribou Mountains. As they flew to retrieve the collar, my father looked down, startled to see a lynx hunkered down on top of the caribou.

“He glared up at us like, you know, ‘Bugger off — this is mine!’ ”

Research shows woodland caribou avoid areas burnt by wildfires due to a lack of lichen and the risk of running into wolves and predators. Stan Boutin, a professor emeritus at the University of Alberta, told me he and his colleagues were surprised to learn that, even in the face of large-scale wildfires, caribou weren’t displaced from their home ranges. They avoided the burned areas — especially during the winter and when the females calve in May and June — but stayed within their ranges.

Similarly, a recent study from 2021, based on data from six woodland caribou ranges in Alberta, found exposure to wildfires didn’t directly lead to death. The paper argues burned habitat is unlikely to be the primary cause of caribou declines in Alberta — and that recovery efforts and conservation ought to focus more on human disturbance.

“In the past, when these big fires burned though there was probably a bump up in the predator numbers for a short period of time,” Boutin says. “But that quickly changes after 40 or 50 years, particularly in the peatland areas. They go back to forest that won’t support moose, so it becomes caribou habitat again.”

The problem isn’t that caribou are maladapted to wildfire, but rather that some ranges in Alberta are so badly fragmented by human disturbance — severed by seismic lines, oil and gas well sites and forestry cutblocks — that their strategy of avoidance is practically null. They’re left with hardly any alternatives of where to go.

My dad points to the Chinchaga caribou range, north of Peace River, that extends along the B.C. border where 81 per cent of the range has been disturbed by oil, gas and timber activities. In the 2000s, he advocated against the use of prescribed fire in the Chinchaga to manage the pine beetle infestation that swept through northern Alberta.

“I was pretty adamant against burning there. The Chinchaga range is hugely dissected by industrial activity and you layer fire on top of that. From a caribou perspective, I couldn’t agree to that,” he says. “And I was pretty unpopular for that.”

Today, despite wildfire being a natural process in the boreal forest, caribou are reaching a critical tipping point where they can’t tolerate losses from both people — and fire. And increasingly, their habitat is being recognized as worth protecting from flames.

Wildfire fighters simply cannot put out every fire that lights in the forest. There are too many, they are too remote or, in some cases, the landscape would be better off letting it burn. So in the jargon-filled vocabulary of wildfire-fighting, deciding which fires to fight or how many resources to put toward them depends on what are known as the “values at risk.” Homes, schools, businesses, power lines are all values.

My father and his colleagues fought within the Alberta government’s wildfire management division for woodland caribou habitat to be considered a “value at risk.” They succeeded in 2015.

Under Alberta Wildfire’s priorities for allocating firefighting resources, “critical wildlife habitat” is included in “natural resources,” to be prioritized after human life, communities, and watersheds and sensitive soils, Josée St-Onge, an information officer with Alberta Wildfire, confirmed with the Narwhal.

“If firefighting resources are limited and the choice is between [fighting] a fire threatening a community or another fire threatening caribou habitat — the choice is obvious,” my dad says. “But at least we got caribou habitat defined as a discussion point.”

Protecting woodland caribou also protects a diversity of other fauna and flora species that favour older forests, including pine marten and boreal chickadees.

“It’s not just caribou, it’s the whole ecosystem,” Laura Finnegan says. She leads the caribou program at fRI Research, based in Hinton, Alta. Several large fires in 2023 swept through the caribou habitat where Finnegan and her colleagues conduct their research in the province. She tells me her team was alarmed by the “unexpected” size and intensity of the wildfires. Moving forward, she says it’s an important conversation to have as a society.

“It’s a question that could extend beyond caribou,” Finnegan says. “How do we account for climate change and these larger events, whether it’s wildfires, rain, snow or flooding, in management plans and conservation efforts?”

When it comes to planning for caribou recovery efforts in the province, environmental critics say the government of Alberta has failed to account for wildfire disturbance. In 2020, the provincial government signed an agreement with the federal government to create what are known as sub-regional land-use plans. These plans would enable the co-ordination of industrial activities with caribou habitat, along with restoration. So far, two of 11 eventual plans have been released, and none have been implemented.

“In the two caribou recovery plans that have been released, including the Cold Lake and Bistcho Lake sub-regional plans, there is no provision to respond to catastrophic natural disaster, or natural disturbances like wildfire,” Tara Russell, program director at the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society’s Northern Alberta chapter, says.

Without accounting for these disturbances, the plans likely overestimate how much habitat can be recovered for caribou within a 100-year time frame. It also poses a risk of over allowing industrial development, she says.

In the current Bistcho Lake plan, if the total area of natural disturbance within the caribou range exceeds one per cent, it would trigger a plan review. But the 2023 wildfires impacted eight per cent of the Bistcho Lake caribou herd’s habitat. That should necessitate a review, Russell says, even though the plan hasn’t yet been implemented.

Critics argue Alberta’s recovery efforts have been delayed and bureaucratic; it’s time caribou simply do not have. The Alberta government is years behind on meeting its obligations to protect caribou, Russell says.

“The agreement is up for renewal in 2025 and yet they’ve barely met the commitments laid out in 2021,” she adds.

In January, the Alberta government released its first report — three years late — on caribou recovery efforts. It found virtually no progress has been made to reduce human disturbance and habitat loss in caribou ranges. Human activity increased in 23 out of 28 caribou subranges from 2018 to 2021. Restoration efforts have barely scraped the surface. Of the 250,000 kilometres of seismic lines that carve up caribou ranges in Alberta, by the end of 2021 only 139 kilometres had been restored.

Boutin says Alberta has historically favoured predator control — culling wolves to reduce the pressure on caribou — over other means of caribou recovery, including the restoration of seismic lines, or investing in maternal penning programs.

“The data is pretty darn strong,” he says. “If you want to keep caribou around and are willing to kill wolves to do it — you can, in fact, do it.”

He’s referring to a study published in April 2024 that found wolf control increased the abundance of southern mountain caribou by 52 per cent compared to a range without intervention. The authors argue that without wolf control, caribou subpopulations will continue to be extirpated before habitat conservation can become effective.

But the wolf cull has been hugely controversial across Canada. Other researchers, including Chris Darimont, a conservation scientist at the University of Victoria, have accused governments of using predator control instead of actually limiting, or halting industrial development — logging and oil and gas — in caribou habitat.

“It’s a very tough, tough decision that has to be made by society,” Boutin says. “If we want to conserve caribou, do we want to do it at the price of ongoing wolf control?”

If we lose caribou in Alberta, Indigenous communities — people who’ve lived closely with caribou, hunting them, subsisting off their meat, using their hides for clothing and weaving them into their identity and worldview — will have the most to lose.

“I’m told [by Elders] that if you hunted a caribou in the fall or early winter, their bones made the best hide scrapers because they were so firm,” Stephanie Leonard, environmental coordinator for the Aseniwuche Winewak Nation, says.

“There was a lot of use for the caribou.”

Members of the Aseniwuche Winewak Nation identify as Cree, Stoney, Iroquois, Beaver, Shuswap and Saulteaux and live in seven communities north and south of Grande Cache, Alberta. Their traditional lands encompass several caribou ranges, including the Little Smoky, a range that’s experienced habitat disturbance of 96 per cent, due to logging and oil and gas.

In 2012, the nation founded Caribou Patrol, an Indigenous-led stewardship program to promote caribou conservation within their traditional territory. In response to the high number of caribou killed by vehicle traffic along Highway 40 — considered one of the “deadliest highways” for caribou in Alberta — they patrol the roads during the caribou’s seasonal migration in spring and fall and record caribou sightings made by the public.

Caribou sightings dropped in 2023, Leonard says, likely a result of the thick smoke that descended from large-scale wildfires burning in the vicinity, obscuring visibility.

“I think there were less people out and about because it was so smoky,” she says. “It was less the fires and more the smoke. It was hard for us to breathe. We could hide in our buildings with our filtered air, but wildlife can’t do that.”

She says people are concerned about the increasingly devastating impact of wildfires on communities. Elders aren’t able to be out on the land, practicing their traditional culture, due to health risks posed by wildfire smoke. She’s also worried about caribou habitat.

“There’s so little good caribou habitat left, there’s a worry that if it burns, where are the caribou going to go? Is that going to be the end?”

The 2023 wildfires decimated 5.5 per cent of the Little Smoky caribou range. Environmental organizations, including the Alberta Wilderness Association, the Northern Alberta chapter of the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society and the Pembina Institute have continually called on the Alberta government to release the Berland and Upper Smoky sub regional plans, for herds located between Grande Prairie and Grande Cache. Both plans are overdue, but so far, it’s still “coming soon”, Russell says.

In the meantime, “to see caribou declining, it’s like losing a part of your world,” Leonard says.

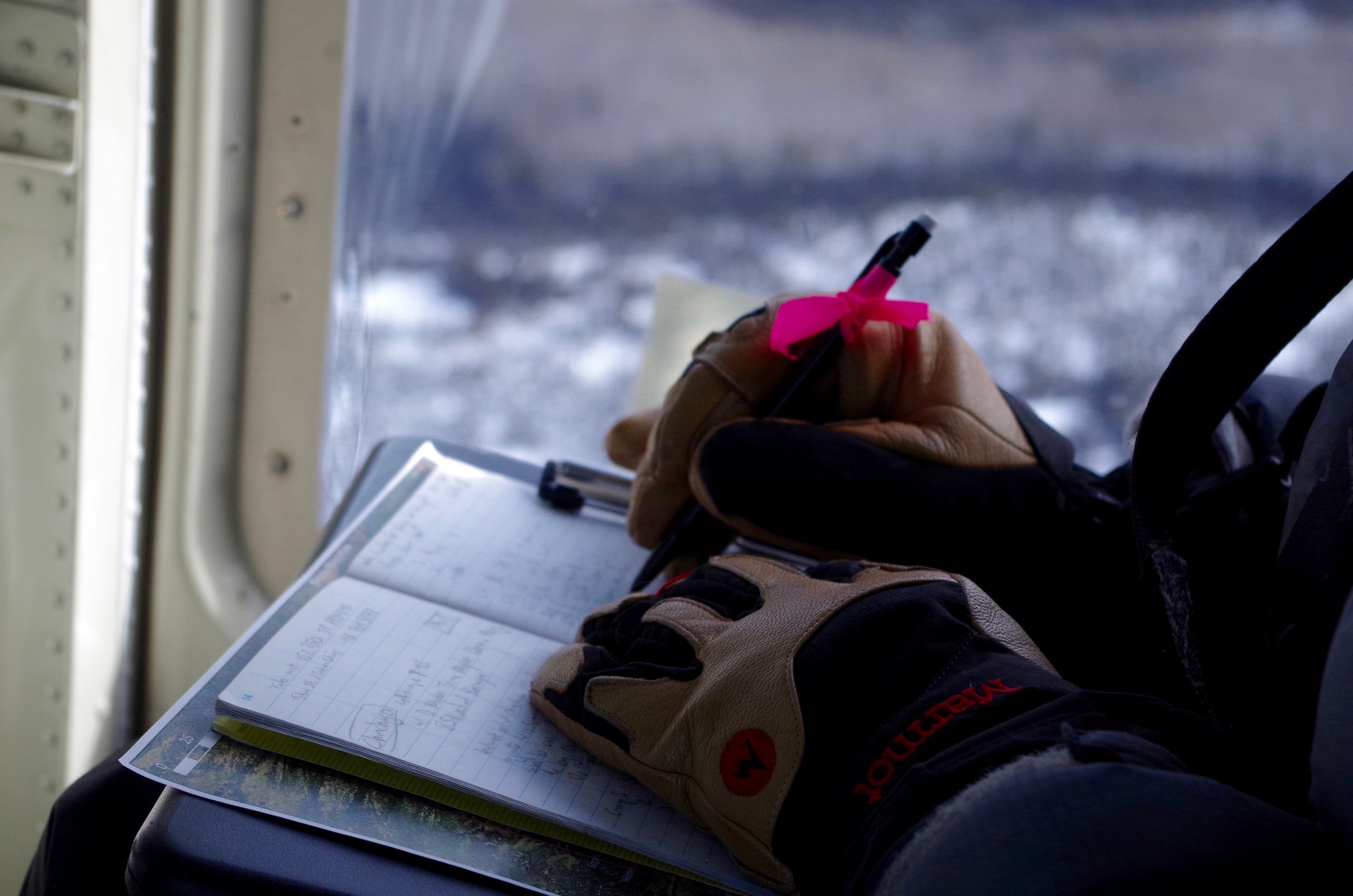

In 2017, I joined my father on one of his final flights over the boreal forest as a biologist. We flew north of Peace River and listened for the signal of the radio collars worn by females.

The plane soared over farmland, cutblocks, well sites, roads, cut lines and the misshapen scars of old burns. We were searching for the Deadwood caribou, a herd that is barely hanging on, my father tells me. The signal pulsed stronger — like a heart beat — and we discovered them hiding in the deep snow in a tightly knit stand of lodgepole pine. At the sound of the helicopter, the caribou fled onto a frozen body of water, grey ghosts not running, but flying across the lake.

Without intervention, most scientists agree the future looks bleak for many caribou subpopulations in Alberta.

There may be hope left for caribou subpopulations in Alberta’s far north, my father says, including herds in the Bistcho Lake and Caribou Mountains ranges, but only with political will: limiting industrial development, restoring disturbances and building wildfire into the equation.

“Their days are numbered,” my father solemnly tells me of the Deadwood herd. “It could take decades, but they’ll eventually blink out.”

My father’s words make me think of a star exploding in the night sky. We’ve reached a tipping point with caribou — one of the few animals to survive the Ice Age and the Holocene. They’ve been here so long and yet they could so suddenly — in a relative blink — disappear.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On a warm September evening nearly 15...

Continue reading

Premier David Eby says new legislation won’t degrade environmental protections or Indigenous Rights. Critics warn...

Between a fresh take on engagement and our new life on video, our team is...

The public has a few days left to comment on Doug Ford’s omnibus development bill....