What’s scarier for Canadian communities — floods, or flood maps?

When maps showing areas most likely to flood are outdated, it puts people and property...

This story was made possible by funding through the Local Journalism Initiative.

An election campaign is well underway in Yukon, and the outcome at the polls on April 12 could have serious impacts for the environment in the territory.

The election follows multiple political shake-ups in Yukon: Kate White’s ascension to leadership of the Yukon NDP following the retirement of long-time party leader Liz Hanson; Mayo-Tatchun representative Don Hutton’s abrupt defection from the Yukon Liberals to run as an independent; and the decision by the Green Party — which did not win a single seat in the territory in the last two elections — to field no candidates for the first time in more than a decade.

The election also comes at a time of serious upheaval for the territory; although Yukoners have been spared many of the more serious realities of the COVID-19 pandemic seen in other parts of the country, travel bans and mandatory quarantines have left the local tourism industry reeling.

More broadly, the territory is grappling with the challenge of balancing First Nations rights and land use with the interests of business and development. Over the past month, two First Nations have launched lawsuits against the government over land use planning issues in their traditional territories.

To get a better sense of what’s at stake, The Narwhal reached out to the three parties — Yukon Party leader Currie Dixon, Yukon NDP leader Kate White and the Liberal Party’s John Streicker, who served as minister of community services in the incumbent Liberal government — to see where they stand on three fundamental Yukon environmental issues: land use planning, clean energy development and climate change.

In advance of Yukon’s April 12 election, The Narwhal spoke to NDP Party leader Kate White, Yukon Party leader Currie Dixon and former minister of community services for the incumbent Liberal Party, John Streicker. Photo: Yukon Assembly and Currie Dixon. Graphic: Carol Linnitt / The Narwhal

Land use planning is an area of constant friction among proponents of resource extraction, First Nations and conservationists.

Under Yukon’s unique agreement with First Nations, the territory is obligated to create land use plans that determine which lands are set aside for protection and which areas will remain open to industry, road building and other forms of development.

Previous missteps with land use plans have landed the Yukon government in hot water. The land use planning for the Peel watershed, for example, precipitated a 15-year legal battle that wound up in Canada’s Supreme Court, where judges ruled the government failed to adequately consult First Nations when deciding how much of the region would be open to industrial development.

Yukoners are watching the process unfold in the Dawson region, where the government has allowed mineral staking to continue before certain ecologically sensitive areas can be set aside for protection.

This could incentivize would-be miners and developers to snap up stakes in areas that would likely be protected under the future plan. Such claims can be grandfathered into land use plans, Sebastian Jones, wildlife and habitat analyst for the Yukon Conservation Society, told The Narwhal. That’s something the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in First Nation and the First Nation of Na-Cho Nyäk Dun have already objected to in the Antimony Creek area near Tombstone Territorial Park.

Dixon acknowledges that land use planning in the Peel is something the Yukon Party, which was in power in the territory from 2002 to 2016, “did not get right.”

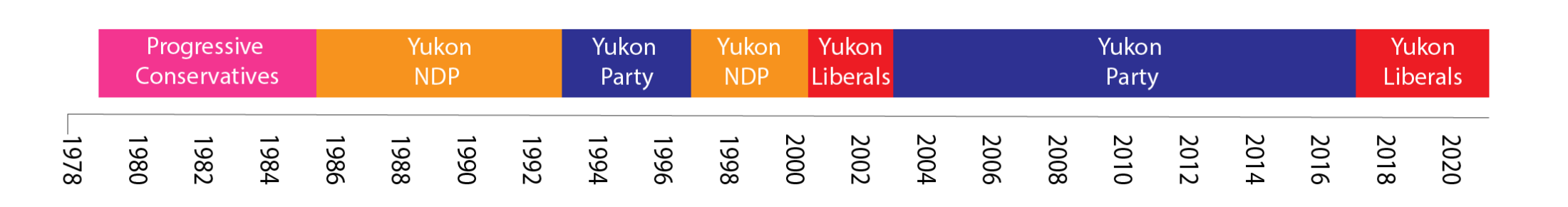

A timeline of Yukon government since the territory became independent after 1975. Illustration: Carol Linnitt / The Narwhal

Recent land use challenges and lawsuits by First Nations stem from decisions made by the Liberal government, which in 2016 campaigned on strong government-to-government relations and consultation with First Nation.

In a recent post on the Yukon Liberal Party’s website, incumbent Premier Sandy Silver made an explicit commitment to pursue “respectful, strong partnerships with First Nations.” The party’s 2021 platform outlines plans to increase regulatory clarity for mineral developers while also “recognizing the importance of land use planning.”

Streicker said recent controversy over land use plans is not for the Liberal Party’s lack of effort or success, although he admitted there have been a few “kinks” in the process.

“If you were to look back over time and say, ‘Have we worked hard at working respectfully with First Nation governments?’ I think, yes, it’s one of our biggest achievements,” Streicker said. “Does it mean that we haven’t had tension and missteps along the way? No. But I really do believe there has been a significant shift on that front.”

If re-elected, the Liberals intend to continue with the Dawson land use plan. Prior to the start of the election campaign, the government withdrew some areas in the Dawson from mineral staking and the Liberals have committed to further withdrawals once planning is completed.

“It’s a commitment in our platform to do more land use planning broadly … we’re going to invest heavily in land use planning for the territory,” Streicker said.

For the Yukon NDP, land use planning and resource development must have the “free, prior and informed consent,” of Indigenous Peoples, as outlined by the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), White said.

“UNDRIP isn’t just a document — it’s a commitment and it has to change our relationships, how we behave, from a government-to-government basis,” she said.

“And — this is an important note — I, as the colonial government, can’t say (for a First Nation) what consent is.”

The Yukon NDP’s 2021 election platform states that land use plans are the “basis for sustainable development in the Yukon” and commits to “protecting at least 50 per cent of the Yukon’s land and waters in partnership with First Nations and the Inuvialuit through land use planning and other available measures.”

White says the party also intends to make “strong commitments” to protect wetlands in the territory, bringing “industrial use” — meaning resource extraction projects like mining — to a “zero” in these areas.

The Ogilvie mountains spread out in the Peel watershed where 67,431 square kilometres of ecologically sensitive land are protected under a land use plan. Photo: Peter Mather

Dixon, who was voted in as Yukon Party leader in May 2020, said although his party has “a pretty strong record when it comes to the implementation of land claims and setting up of new protected areas throughout the territory,” it needs to do a better job of working with Yukon First Nations, particularly at the government-to-government level.

The Yukon Party’s 2021 election platform mentions an explicit promise to complete the Dawson land use planning process only in a section devoted to the party’s commitment to mining. However, the platform also includes numerous commitments to advancing the interests and economic opportunities of First Nations in the spirit of reconciliation.

“I think now as we go forward with land use planning throughout the territory, we — all Yukon, government, First Nations and others — all have a much better sense of what the process is supposed to look like, and how we all need to engage it,” Dixon said. “I think, having learned those lessons, and having had that experience, we will be well positioned to move ahead in a much more collaborative and effective way.”

The lion’s share of energy needs in Yukon is met through hydroelectricity developed in Whitehorse.

But when demand exceeds capacity — a common occurrence during winter months, when electric heating and increased indoor time strain the power grid, or when water levels are low — the grid is supplemented with power from fossil fuels. So energy may be coming from fossil fuels even when homes are heated with electricity or people choose to drive electric cars.

The power grid also remains “islanded,” Streicker said, meaning it is not connected to other, larger networks in Alaska or British Columbia. Additionally, many Yukon communities outside of Whitehorse remain off the main grid, relying on imported, heavily polluting diesel for power.

Read more: How can Canada’s North get off diesel?

Yukon spends about $60 million every year on heating, with $50 million going to fossil fuels imports that are driving up the territory’s greenhouse gas emissions. Heating currently accounts for one-quarter of the territory’s overall emissions and makes up one-half of the Yukon government’s emissions.

So what do each of the three parties propose?

Dixon, from the Yukon Party, said the best solution is to clean up the territory’s backup energy sources.

“The reality of an isolated grid is that fossil fuels will continue to be a part of our grid for the foreseeable future, we’ll always need that backup power, but the goal for us should be to reduce our reliance on that as greatly as possible.”

“Our vision going forward is to add significant renewable energy projects to … the grid,” he said, adding that his party would encourage renewable initiatives for homeowners and small businesses through financial incentives.

“There’s ways to add renewable projects to the grid … whether it’s through the microgeneration policy or the independent power producer policy. Those are both policies that we introduced in our last term in government and ones that our platform will contemplate enhancing and expanding over the course of the next few years,” he said.

The Yukon Party’s platform notes that, if elected, the party will explore the creation of a LNG (liquified natural gas) energy facility in Whitehorse, the development of hydrogen and the option of expanding the Yukon grid to B.C.

The Yukon NDP, meanwhile, would consider expanding the territory’s limited hydro grid. White said Yukon has created a false narrative around diversified energy sources, giving Yukoners the choice between diesel fuel and LNG, without offering large scale renewable projects as an alternative.

“If we look at our diesel communities, we need to be doing everything we can to support them to cut down on that diesel until we have the ability and enough (renewable) generation to be able to get transmission lines out,” she said. White also noted there are newer and better technologies for renewable power storage and building strategies the territory could exploit to make green power generation more efficient.

In its platform, the NDP pledges an “out-right ban” on all fracking and “non-renewable energy extraction” in the territory. The party also says it will investigate a territory-wide energy grid, legally mandate energy efficiency in buildings and immediately fund research for thermal heating, geothermal development, small-scale hydro projects, pumped storage, wind, solar and the use of biofuels.

Read more: Yukon’s climate plans rely on biomass. But is it actually good for the environment?

Streicker said the Liberal Party’s goal is for renewables to generate 97 per cent of the territory’s power and to connect communities not currently on the grid, such as Beaver Creek and Watson Lake. The Liberals support bringing in renewable energy from the Taku River Tlingt’s hydroelectric project near Atlin, B.C., which would involve upgrading transmission lines from Jake’s Corners to Whitehorse or Carcross.

The proposed Moon Lake pumped storage project, which would see renewable energy held in reserve, is “the ideal,” for the Liberals, Streicker added.

“With respect to reducing our fossil fuels, we absolutely have to shift the energy economy,” Streicker said. The Liberal’s platform also lists commitments to investigate the use of geothermal for both electricity and heat, construct a biomass plant, invest in renewable energy projects in partnership with First Nations and support solar and other micro-energy projects.

A mother fox and her kits out and about in Whitehorse, Yukon, where the species is a now-common sight. As the temperature has risen in the North, red foxes are now able to survive and thrive where they couldn’t before. Photo: Peter Mather

Like much of the North, the Yukon is experiencing the effects of climate change, including thawing permafrost and changes in precipitation, more severely and faster than the rest of the country.

“If you’re asking if we need to reduce our greenhouse emissions or adapt to climate change (in Yukon), it’s not an ‘or’ question, it’s an ‘and’ question,” Streicker said.

Both White and Streicker noted the toll that transportation — cars, trucks, planes — takes on the territory’s emissions and both parties want to “electrify” the Alaska Highway, creating electric vehicle stations so people can use electric cars to move back and forth between communities. Both parties identified transportation as a major issue for the territory in terms of carbon emissions, with Streicker adding that “more than half” the territory’s emissions are generated from transportation alone.

Yukon is a small emitter compared to other provinces, but the territory’s emissions are on the rise. According to the Yukon government’s most recent data, emissions grew by 11.8 per cent between 2009 and 2017, the most recent year for which data is available. Emissions from transportation grew by 14 per cent during the same period.

The Yukon Liberal’s climate plan, Our Clean Future, cited an emissions reduction goal of 30 per cent by 2030. The party’s platform doubles down on the plan, and includes proposed rebates for electric vehicles and bikes and more charging stations. The platform also supports development of climate adaptation, green home building plans, the promotion of sustainable tourism and wildfire prevention.

But White said the Liberal’s climate plan doesn’t go far enough because it doesn’t address emissions from the territory’s mines. Mining is the single-largest private contributor to the territory’s economy.

“I have concerns that the Our Clean Future plan does not include mining in its reduction target and I’m concerned (the target) is too low,” she said.

The NDP would like the target increased to a 45 per cent reduction in emissions by 2030 and would like to see mining emissions included in the calculations, she said. The NDP platform also pledges to require Yukon mines to meet absolute emissions reductions standards, not intensity targets.”

The Liberal’s Our Climate Plan proposes establishing intensity-based targets for mines in 2022.

Read more: Will mining be the sleeping giant of Yukon greenhouse gas emissions?

According to Roxanne Stasyszyn from Yukon’s Department of Environment, mining emissions make up 10 to 15 per cent of the territory’s total emissions on average, although they fluctuate from year to year depending on the amount of mining activity taking place.

Emissions from mining are calculated based on how much fuel is purchased for mining activities, which is tracked through fuel tax exemption permits and includes fuel used onsite at mines, but not fuel used to transport materials, equipment, or people to and from mine sites. Those activities are captured under other emissions categories such as road transportation and aviation. Mining emissions are tracked separately from other emissions because the variability of the industry makes setting limits for emissions difficult, Stasyszyn told The Narwhal.

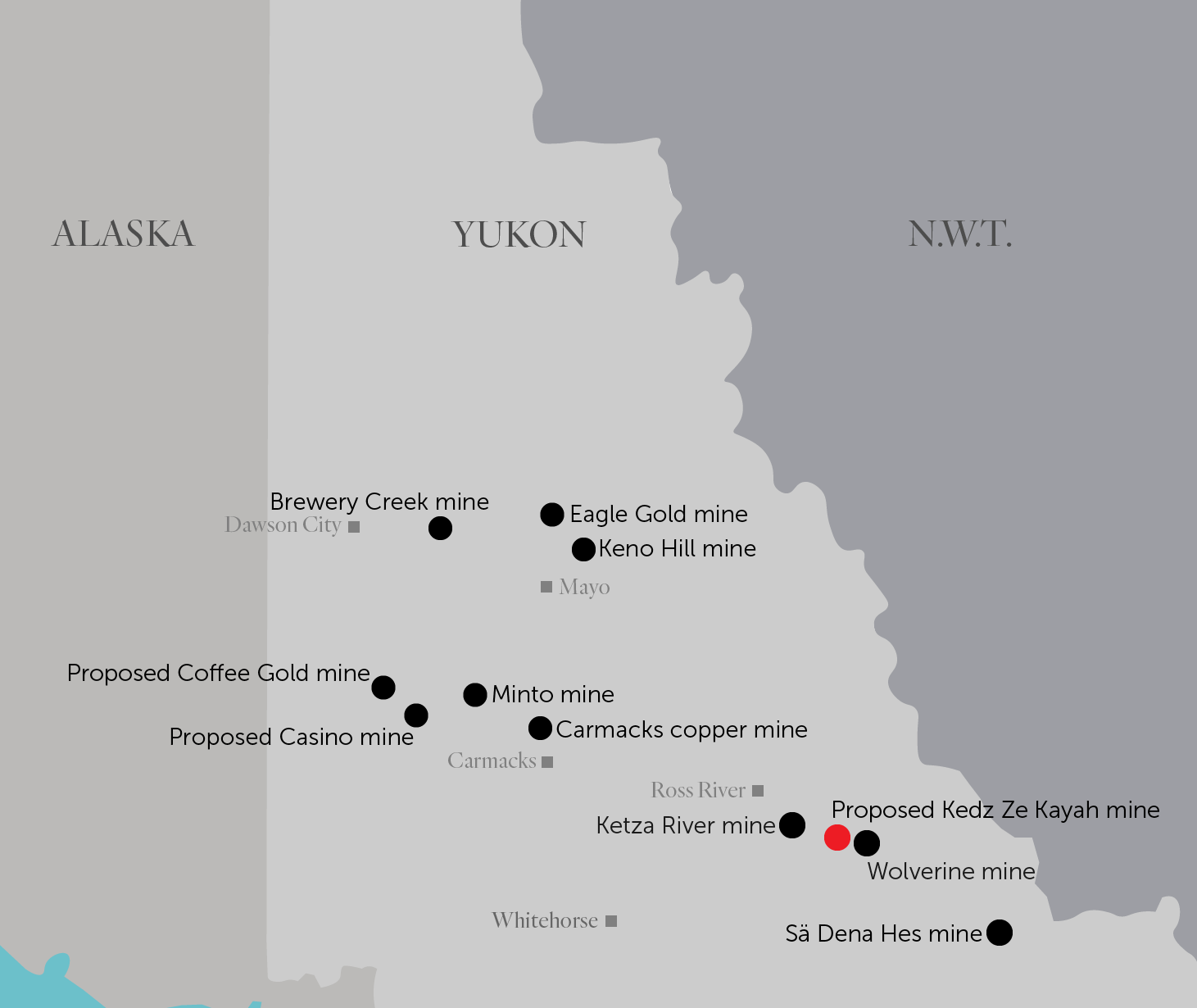

Mines connected to the grid, like the Victoria Gold Eagle Gold mine, near Mayo, produce relatively few emissions. However, off-grid mines can be very large emitters if they’re powered by fossil fuels.

Newmont’s Coffee Gold project, near Dawson City, will use diesel power to produce about 19 million kilowatt hours of energy annually — enough electricity to power about 1,360 Yukon homes for one year. The mine is expected to produce about one million tonnes of carbon dioxide over its 12-year lifespan. The off-grid Kudz Ze Kayah mine is anticipated to produce roughly 110,000 tonnes of emissions over 10 years.

Location of many mining projects, in operation or proposed, in Yukon, including the off-grid Kudz Ze Kayah mine in the southeastern portion of the territory. Map: Carol Linnitt / The Narwhal

Streicker said significant drops in mining sector emissions — which can happen when a mine closes — have been treated in the past by Yukon Party governments as though large climate commitments have been met, which is, in part, why the Liberal Party counts mining emissions separately.

While the Yukon Party is committed to supporting the mining industry, Dixon also noted that nature is important to “a lot of Yukoners,” saying his party wants to ensure the environment is protected while also balancing economic interests and jobs.

“I want to see a healthy and sustainable mining industry here in the territory, and I want to make sure that we continue to promote the territory as an attractive place to invest in mining opportunities, but also to create opportunities for local citizens,” Dixon said.

He said the party will be taking “significant action against climate change and ensuring we do our part to address this challenge as part of a Canadian effort and a global effort.”

“We want to see some action taken to address climate change, and we recognize that it’s a significant challenge for all of us.”

Enbridge Gas will face Waterloo Region in a hearing before the Ontario Energy Board to renew an agreement that would allow the company to continue...

Continue reading

When maps showing areas most likely to flood are outdated, it puts people and property...

We’re suing the RCMP for arresting a journalist on assignment for The Narwhal. It’s an...

As glaciers in Western Canada retreat at an alarming rate, guides on the frontlines are...