Canadians have another facet of national defence right under our noses

The current trade war with the U.S. means Canada must confront whether its domestic food...

At the end of the 19th century, around the tail end of the Klondike Gold Rush, the chief of the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in First Nation warned against the overhunting of the Fortymile caribou herd, a food source for local Indigenous communities that was then feeding an influx of hungry miners.

Chief Hä`hkè Isaac’s protest went unregarded, though, and within a few decades the once-mighty herd experienced a precipitous decline.

Estimates of the herd’s population in 1920 put the number of Fortymile caribou as high as 568,000 animals. Just a decade later, that number dropped to roughly 10,000. By 1973, the herd hit a historic low of just 5,740 caribou.

Incredibly, recovery efforts have seen a dramatic turnaround for the herd in recent decades. Due in part to voluntary hunting bans — the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in haven’t harvested a caribou for more than 20 years — the herd is on the rebound. As of 2017, there were about 84,000 caribou in the Fortymile population.

The dramatic rise and fall of caribou numbers demonstrate how incredibly sensitive this migratory herd is to human activities, like hunting, road-building and mining.

That sensitivity is at the heart of a brand new Fortymile herd harvest management plan, developed by the Yukon Government and the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in First Nation, that will carefully chart the population’s response to the reintroduction of the nation’s subsistence hunting, among other ongoing pressures.

Hunting actually has an important role to play because the herd’s dramatic increase in size isn’t all good news, Mike Suitor, a regional biologist with the Yukon government, told The Narwhal. “If you have too many animals in one patch of habitat, at some point or another, that’s not healthy.”

“With a herd like this, you need to be prepared to deal with the full range of the population because they do increase and decrease very quickly,” Suitor said. “And most herds go off the cliff when they decline.”

The new plan will help track both increases and decreases in the herd, he added, which will be critical moving forward, especially as the territory also has to co-manage the population with Alaska.

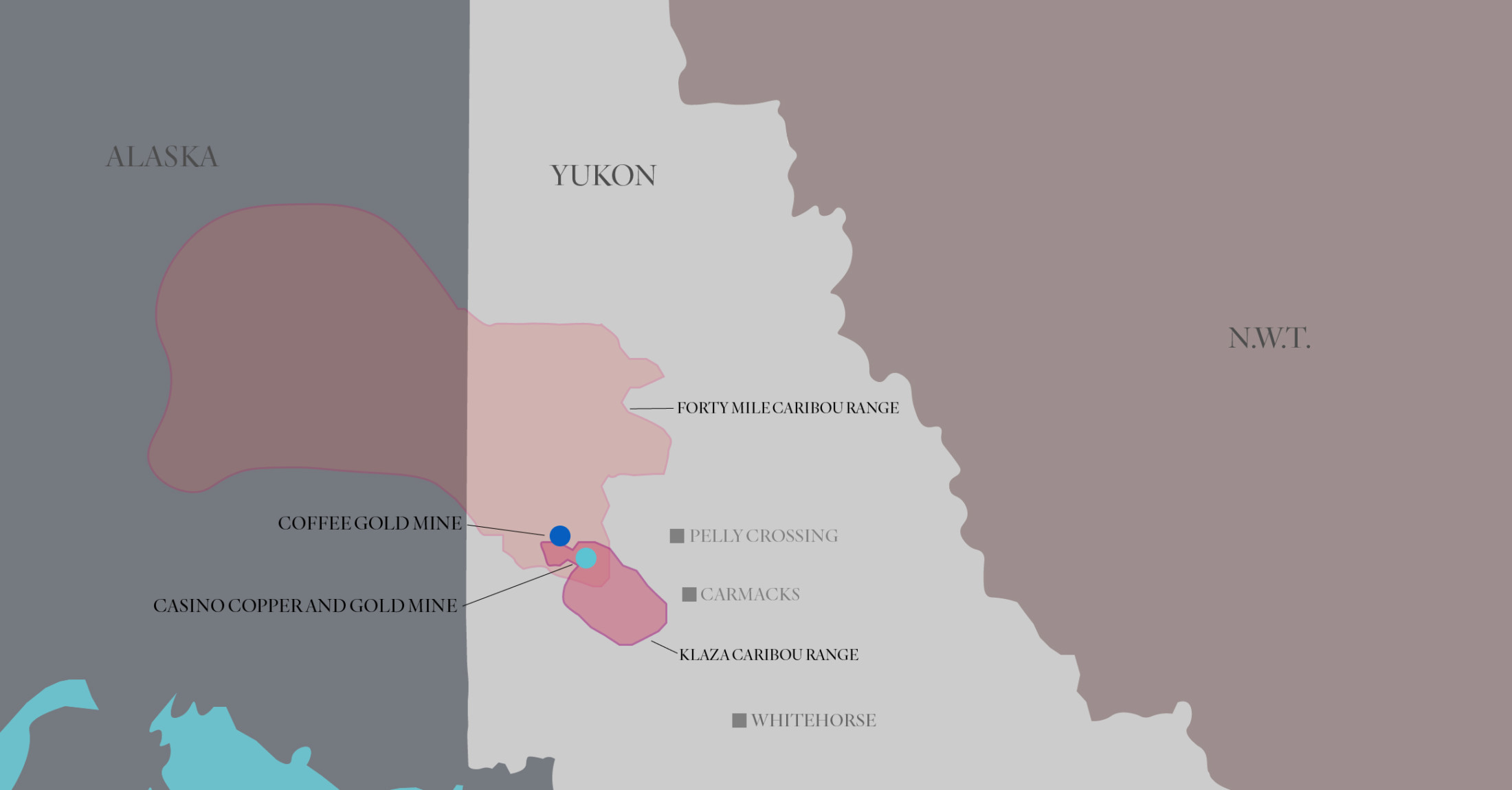

A map showing the location of the Fortymile caribou herd’s range. Map: Carol Linnitt / The Narwhal

The issue of how many Fortymile caribou can be harvested — and by who — has been a fraught one for decades.

The herd’s most recent range in Yukon is primarily found in the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in First Nation’s traditional territory. In the 1990s, the nation asked its citizens to voluntarily refrain from killing any caribou.

In 1995, the Yukon government banned hunting Fortymile caribou for non-Indigenous hunters. At the time, the herd’s population was around 23,000.

Earlier this year the Yukon government opened two licenced harvests of the herd, angering the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in, which called on the territorial government, twice, to cease all hunting of the herd until the harvest management plan was in place.

The Yukon government’s hand may have been

forced by the Alaskan government, with which Yukon coordinates management of the transboundary herd through harvest allotments. Alaska, concerned the herd was growing too big for its range, announced it would take Yukon’s allotment if the territory didn’t use it.

Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in Chief Roberta Joseph told The Narwhal the management plan is designed to ensure harvesting is done correctly, without impacting the herd’s health.

“Licenced harvesting, as there was in the past, had actually gotten us into the position [of needing recovery] … in the first place, because there was no control of scientific or Traditional Knowledge of the herd,” she said.

The new harvest plan has a specific goal of renewing the relationship between Yukon hunters and the Fortymile caribou “through incrementally increased harvest of the herd,” the document states. It also notes the herd’s population has rebounded to the degree that “everyone’s” harvesting needs in Yukon can be met.

That represents a significant departure from the no-hunting holding pattern that only recently started to be undone, Joseph said.

“We haven’t had a cultural and traditional relationship with the caribou for a long time,” she said. “We have to regain that relationship and regain the knowledge and the stories from our Elders on the caribou.”

For the first time in two decades, the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in organized a community subsistence harvest where families were encouraged to harvest a caribou along the Top of the World Highway, northwest of Dawson City, and share the meat with Elders.

The new harvest plan will expand monitoring efforts in order to shape when and where permit and subsistence harvesting takes place and when to introduce caps.

The goal, now that hunting is back on the table, is to stabilize the herd’s population until the caribou expand their ranges in Yukon, Suitor said.

The herd’s summer range, which stretches from north of Fairbanks, Alaska, to southwest of Dawson City, can’t sustain that many caribou for much longer, Suitor said. Year after year, the caribou arrive at the same place, which can gradually diminish their habitat until it’s gone. At worst, this can cause die-offs, he added.

“We think that there’s just too many caribou on the existing summer range,” Suitor said. “Quite often how these herds decline is an overuse of summer range.”

Hunting is part of the solution to stabilize the herd’s population in specific zones, Suitor said.

According to the new plan, licenced harvests will occur twice per year, from Aug. 1 to Sept. 9 and Dec. 1 to Mar. 31. The harvests can take place within a zone that includes the Top of the World Highway, along the Yukon River surrounding Dawson City and the Goldfields south of Dawson.

This zoned “split hunt” was designed to ensure First Nations’ harvests aren’t interfered with, Suitor said.

“We know that when a lot of caribou show up on a highway, and word gets out, it can get silly — I mean, a lot of people can come,” Suitor said. “We want to ensure subsistence harvesters aren’t impacted in any way, shape or form and they have the potential to participate in this hunt without being overcrowded.”

Caribou from the Fortymile herd congregate on a road in Yukon. Caribou spotted on the Top of the World Highway can draw large hunting crowds. Photo: Steve Hossack

Subsistence hunting can continue year-round without permits or caps.

If the herd starts to drop, however, “that’s where you want to maybe lay off harvesting,” Suitor said. “You want to do things like not harvest cows and maybe focus on bulls. What this plan allows us to do is address all of that — it gives us that ability to fluctuate, based on the condition of the herd.”

As a part of keeping tabs on the health of the herd, the Yukon government will roll out a series of new monitoring efforts.

GPS Collars, for example, will be used to not only keep track of the caribou’s population and movement, but to assess the degree of habitat overlap with other herds in the region, including the Klaza and Porcupine caribou.

Human activity, identified as a “primary concern” when it comes to the Fortymile population’s health, will also be monitored in the herd’s range, particularly through tracking traffic volume.

The number and types of vehicles will be tracked in key areas, like the Top of the World Highway, to generate data on the “potential use of the area (e.g., mining, hunting) where possible,” the plan states.

There are a number of roads, mining and resource projects within the Fortymile caribou herd range.

The Yukon environmental and socio-economic assessment board recommended the Yukon government also track cumulative effects on the herd and report them to “ensure significant adverse effects do not occur from the culmination of individual projects in the range.”

Following through with this goal will require ongoing habitat modelling assessment, along with tracking the ecological footprint of mining projects, the plan states.

A central tenet of the plan is that it remains flexible as it is implemented over the next year, Suitor added. That’s why the plan will undergo periodic reviews to determine whether any updates are needed. The first such review will occur in 2025.

The Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in First Nation is able to harvest caribou from the Fortymile herd for the first time in more than 20 years thanks to recovery efforts. Photo: Steve Hossack

While the Yukon government has conducted research into the Fortymile caribou for years, these efforts will be expanded, with the help of Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in, Suitor said.

All harvest data, including the number and sex of animals, along with where and when they were killed, will be exchanged between the Yukon and Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in governments every year to make more informed decisions, he said.

Co-management lies at the heart of the management plan, with every decision made in lockstep with the First Nation, Suitor said.

“What’s new is the structure that we’ve built to come together to analyze that data together and then make decisions,” he said. “We’ve always had dialogues, but it’s formalized now. Everyone knows what to expect, when to expect it. It allows us to make sure we’re doing things right and that we’re doing it together.”

Joseph said it’s crucial each government is aware of the herd’s overall health and what could be affecting it. This makes the sharing of information so important, she added.

“The agreement provides to work together collectively to review the indicators on the health of the herd,” Joseph said, adding this allows for informed decisions. “It gives a more comprehensive determination of cooperative management of the herd.”

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On March 17, federal Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre...

Continue reading

The current trade war with the U.S. means Canada must confront whether its domestic food...

Residents and nearby First Nations wanted a new environmental impact assessment of the contentious project....

Growing up, Christian Allaire loved spending summers with his cousins in his grandma’s backyard, near...