Our trial is a week away

We’re suing the RCMP for arresting a journalist on assignment for The Narwhal. It’s an...

An analysis by The Narwhal of new data released by the province raises questions about whether Albertans are collecting a fair share of the wealth created by oilsands development.

Royalties are the price charged by a resource owner — in this case Albertans — for a producer to extract and sell a non-renewable resource. Alberta has long been criticized for having royalty rates among the lowest in the world and failing to save for future generations.

Since 1998, oilsands production has soared from nearly 800,000 barrels a day to more than 2.8 million barrels a day. According to recent projections by the National Energy Board, oilsands production will hit 4.5 million barrels a day by 2040.

A much-maligned review of Alberta’s royalty system in 2015 came to the conclusion that the “current share of value Albertans receive from our resources is generally appropriate.”

The Narwhal analyzed 2017 royalty data published by Alberta Energy and federally mandated Extractive Sector Transparency Measures Act (ESTMA) reports to investigate whether that is truly the case.

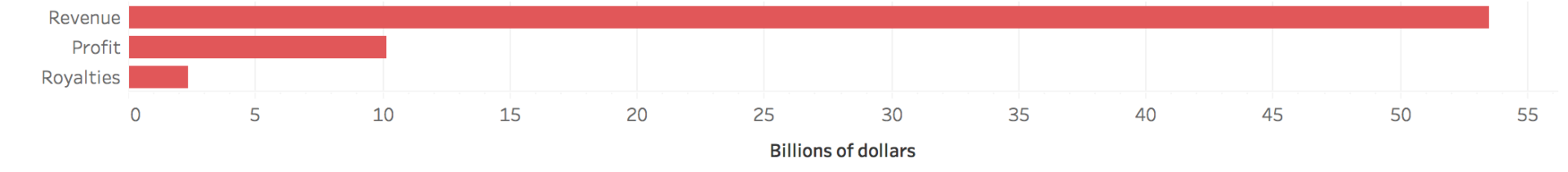

Alberta’s 30 most productive oilsands projects accounted for more than 95 per cent of oil produced in 2017, generating $53.5 billion in revenues.

The companies producing that oil — including Suncor, Cenovus, Canadian Natural Resources Limited and Imperial Oil — made $10.14 billion in profits, while Albertans collected $2.37 billion in royalties.

in 2017 Alberta collected a mere $2.37 billion in royalties for the 30 largest projects in the oilsands which all in generated more than $53 billion in revenues. Graphic: Jimmy Thomson / The Narwhal

That means the biggest oilsands companies paid a total royalty rate of 23.37 per cent of profits.

The billion-dollar question is: how does this compare with what oil companies pay in other places around the world?

To get a clear picture of that, you also have to consider corporate income tax rates.

As reported in individual ESTMA reports, companies paid a total of $751.06 million in taxes and another $87.65 million in fees in 2017. In total, the top 30 oilsands projects paid $3.21 billion in royalties, taxes and fees to various governments — meaning governments collected 32 per cent of profits.

Documents filed by Kinder Morgan Canada to the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission indicate the cost of twinning the Trans Mountain pipeline may now cost up to $9.3 billion. Those costs will be paid by the federal government, assuming the company’s shareholders vote to approve the sale of the existing pipeline for $4.5 billion at the end of this month.

Jim Roy, an Edmonton-based royalty consultant and a former senior advisor on royalty policy for Alberta Energy, told The Narwhal that Alberta’s rates can be compared to government returns in Saudi Arabia (85 per cent), Norway (78 per cent), China (63.5 per cent) and Australia (58 per cent).

Canada captures roughly 32 per cent of oil industry profits, far lower than some other major oil-producing nations. Graphic: Jimmy Thomson / The Narwhal

Different jurisdictions collect revenue on non-renewable public resources in different ways. Norway, for instance, charges a standard corporate tax rate of 23 per cent and a special petroleum tax rate of 55 per cent, bringing the total to 78 per cent.

If Alberta applied a flat 78 per cent rate to profits generated by the top 30 oilsands projects, it theoretically would have collected $7.91 billion in 2017 — $5.54 billion more than it did.

At last count, the Alberta deficit was $8 billion.

The first stage of Calgary’s Green Line LRT costs $4.65 billion, while the long-awaited Edmonton southwest hospital may cost up to $2 billion.

“In Alberta, the public owns the resources so theoretically we’re entitled to 100 per cent of the resource rent,” said Regan Boychuk, an independent researcher and member of the province’s 2015 Oil Sands Expert Group.

“Industry should cover all their costs and make a reasonable profit. But after that, everything that’s left belongs to the public.”

Boychuk estimates 10 per cent is a reasonable expectation for annual profits.

That would leave 90 per cent on the table for resource owners and governments.

Even if Alberta followed Norway’s model, oilsands producers would still receive 22 per cent of profits.

In 2005, the province’s energy department noted: “A decision to not capture the full [economic rent] amounts to a decision to sell the province’s resources at less than their full value.”

Alberta’s generous royalty system was designed to entice companies in the early days of the oilsands to make big, risky multi-billion dollar capital investments.

The royalty regime was first recommended by the industry-stacked National Task Force on Oil Sands Strategies in the mid-1990s, and has been largely untouched since.

A number of factors were listed in the rationale for continuing Alberta’s royalty regime with minor changes during the 2015 royalty review — the high upfront costs of production being a major one.

“There could have been a stronger case made in the ’80s and ’90s for low royalties, to get the industry off the ground. That’s not the same argument to be made today,” said Ricardo Acuña, executive director of the Parkland Institute.

According to the Alberta government, only 21 per cent of proven oil reserves in the world are open to private investment. More than half of those reserves are in Alberta’s oilsands.

Here’s a quick primer on how Alberta’s royalty system works.

There are two categories of oilsands projects when it comes to royalties: “pre-payout” and “post-payout.”

Payout refers to the moment when all the revenues a project has generated finally overtake the costs incurred by a project in its lifetime. Essentially companies reach a point where they’re getting more out than they’re putting in — and this can take some time as these projects are costly.

Royalty payments themselves are a deductible expense when calculating costs.

Importantly, projects are assessed on an individual basis, not company wide. (This means that a big, established company could bring on a new project and not have to pay serious royalties on it for years, compared to if it had been assessed company-wide, in which all profits would be charged regardless of the source.)

In pre-payout, projects pay a royalty rate of one to nine per cent of gross monthly revenues based on the price of West Texas Intermediate (WTI).

In post-payout, they pay between 25 to 40 per cent of yearly profits, also dependent on the price of oil.

According to the new data from the province, 12 of the 30 most productive oilsands projects are in the “post-payout” category, each paying about 27.41 per cent of their profits. Another 16 are still in “pre-payout” phase, paying only 2.29 per cent of gross revenues.

Project returns vary greatly.

Four of the top 30 oilsands projects reported net losses in 2017, but the remainder received far more profit than was paid out to the government.

The most extreme example was Cenvous’ 200,000 barrel-per-day Christina Lake project, which generated more than 16 times more profit for the company than it did for governments in the from of royalties, taxes and fees.

Suncor’s 180,000 barrel-per-day Firebag project made a profit nearly eight times larger than the amount paid to governments.

All projects, whether in pre-payout or post-payout, deduct all diluent costs before their royalties are calculated.

Diluent is the substance — natural gas condensate or naphtha — that is mixed with raw bitumen to transport it to refineries. About 60 per cent of bitumen produced in the oilsands is mixed with diluent. The remainder is upgraded into synthetic crude before being shipped off to refineries.

Synthetic crude sells for significantly more than dilbit due to its higher quality. Unlike dilbit, it can be refined at a conventional refinery. Producers that produce synthetic crude can transport about 30 per cent more bitumen in pipelines as a result of not mixing it with diluent.

Of the 30 largest oilsands projects, only six didn’t use diluent. In 2017, the top 30 companies spent $18.21 billion on diluent, or more than one-third of total revenues. In many cases the diluent itself is worth more than the bitumen it’s mixed with. It’s an extremely expensive process, the direct result of not having enough upgrading capacity.

The largest 30 projects received an average of $55.70 for every barrel sold in 2017. Deducting the cost of diluent means that almost $19 of that value wasn’t touched by royalties.

For example, Cenovus’ Christina Lake project extracted $4.83 billion worth of oil in 2017, the most of any oilsands project. But its diluent costs were $2.38 billion. That means that only $2.45 billion was assessed by the province with the 2.3 per cent royalty rate, resulting in a $58.26 million royalty bill.

A dozen of the 30 largest oilsands projects have reached that post-payout stage in which they pay higher royalties.

On average, those 12 projects received $52.60 per barrel in total revenue in 2017. But then diluent was subtracted (average of $12.58), operating costs (average of $16.34) and capital costs (average of $4.05).

That left an average of only $19.65 per barrel left to assess for royalties.

Boychuk described this royalty structure as paying for costs with “free oil,” in which enormous amounts of oil revenue go unassessed for royalty payments.

“The industry always claims that it’s very high cost and nobody makes any money,” Boychuk said.

“All of the oil is produced for free. If you want to build a $40 billion project, you get $40 billion in free oil to do so. You get free oil to pay your dump truck drivers six figures, all the operating costs are all paid for with free oil. That’s the real reason we collect such a minuscule percentage of oil and gas dollars generated.”

If royalty rates were increased, it would likely impact the pace of development — which could be a good thing or a bad thing, depending on how you look at it.

“Low royalty rates tend to result in a higher pace of development and a desire to attract private investment,” Roy wrote. “Higher royalty rates are associated with a strong role for a national agency to manage the pace of development and restrictions on the amount of foreign or private investment allowed.”

The other big question is where the profits made by oil companies really go.

“There’s tremendous level of employment and wealth created in the province that I think we really have no idea where the money flows,” said Barry Rodgers of Rodgers Oil & Gas Consulting and team lead for the 2007 Alberta Royalty Review.

“If you give royalty relief and that amount stays in the province, then it’s a matter of how we spend our money. If it leaves the province, then there’s another question. Those things are not explored very well.”

Rodgers, who served as executive director of the economics and markets branch for the Alberta Department of Energy between 2008 and 2010, told The Narwhal he’s hesitant to prescribe royalty rates as it’s a complicated equation with many potential impacts.

But he said we do know what low royalties did in retrospect: started a high-paced cycle of investment activity that overheated the sector, allowing high-cost projects to pass the economic test and be developed.

Once the oil price collapsed, it left many people laid off who wouldn’t have been hired in the first place if there was a “more cost-conscious fiscal policy,” he said.

“And you’ve got a dilemma now,” he said. “You have created a situation where the royalty is causing projects to come on. They’re on the margin, these projects, and as soon as the price changes these projects are no longer economic. Then what do you do? You have a bunch of people that invested their careers and lives and families and everything else. It’s not so easy then to say ‘we should increase the royalties’ like a lot of the academics do, and like I did.”

Boychuk said the entire case being made by government and industry that new pipelines will guarantee higher prices and better returns is “pretty debatable” given that Albertans still only receive a tiny fraction of the value of the oil.

In 2017, the province was paid 4.5 per cent of the oil’s value in royalties. Even when all taxes and fees are combined with those royalties, governments only received six per cent of revenue: $3.21 billion in total.

At last count, the Alberta Energy Regulator estimates it will cost at least $23.2 billion to clean up the oilsands tailings ponds. Environmental Defence reports that it may be double that, with its online counter now nearing $50 billion in largely unfunded liabilities.

All in all, the royalty regime combined with these unfunded liabilities calls into question a central argument of building more pipelines: that increased oilsands production will mean significantly larger revenues for schools, hospitals and roads.

“The fact of the matter is that industry keeps 96 cents of every dollar,” Boychuk said. “If we marginally increase the size of the pie, we’re still only getting four per cent of it. Four per cent of a marginally bigger pie amounts to a rounding error.”

Enbridge Gas will face Waterloo Region in a hearing before the Ontario Energy Board to renew an agreement that would allow the company to continue...

Continue reading

We’re suing the RCMP for arresting a journalist on assignment for The Narwhal. It’s an...

As glaciers in Western Canada retreat at an alarming rate, guides on the frontlines are...

For 15 years and counting, my commute from Mississauga to Toronto has been mired by...