Canadians have another facet of national defence right under our noses

The current trade war with the U.S. means Canada must confront whether its domestic food...

It’s been a full decade since the office of the auditor general turned its spotlight to the country’s 255 mines.

The last time the auditor general looked at mining, Canada’s environment commissioner found the country was essentially failing to protect fish habitat from the impact of mines.

(Wait, what exactly is the office of the auditor general? It’s an independent body that has the responsibility to audit the operations of governments and reports back to Parliament. In other words: it’s a watchdog. The auditor general also appoints the environment commissioner.)

In the past decade, Canada has had time to clean up its act on mining and, according to the auditor general, has made some improvements in protecting fish under the Fisheries Act.

However . . . ahem . . .

There are still some significant and rather startling gaps in Canada’s regulation and monitoring of mines, according to environment commissioner Julie Gelfand’s latest report. The new audit looks specifically at Environment and Climate Change Canada and the Department of Fisheries and Oceans to assess how well these departments are doing at protecting fish from mines.

Here are eight key takeaways from Tuesday’s report.

That’s right. Canadians have been promised these regulations for years, but their creation has been endlessly drawn out.

That’s why those sprawling metallurgical coal mines contaminating water with selenium in B.C.’s Elk Valley are creating a very awkward situation in Ottawa. While the company that owns and operates the mines, Teck Resources, is in clear violation of B.C.’s pollution guidelines, those are provincial ‘guidelines’ and not law.

While the province has jurisdiction over the extraction of natural resources and resulting pollution, it’s the federal government’s job to protect fish.

I know what you’re thinking: ‘but isn’t Teck Resources polluting fish bearing waters and isn’t that in violation of the Fisheries Act?’ You’re not wrong.

But technically there are no specific regulations for non-metal mines under the Fisheries Act, so it’s difficult (but not entirely impossible) for the federal government to point to which rules the company is breaking.

Because oilsands, potash and coal mines aren’t guided by regulations under the Fisheries Act, they are given no permission (basically no permits) to pollute fish-bearing waters (metal mines are granted this permission).

A flowchart showing no regulations for non-metal mines under Canada’s Fisheries Act. Source: 2019 Spring Reports of the Commissioner of the Environment

For this reason the report states: “Non-metal mines other than diamond mines are not permitted to release any effluent containing harmful substances into a body of water where fish are present. The requirements for non-metal mines are therefore more stringent than those for metal mines.” (emphasis added)

Tell that to people in Fort Chipewyan or Sparwood, why don’t you?

The audit found Canada is only likely to inspect a non-metal mine if a spill has occurred.

The auditors note this lack of inspections is not based on a “comprehensive risk analysis.” Mining inspections at non-metal mines are particularly important because non-metal mines are not permitted to release any harmful substances into fish-bearing waters (see above) and yet, some still are.

Between 2013 and 2015 Environment Canada “identified a need to develop a risk-based strategy for non-metal mines, but it did not develop such a strategy,” the report states. Further, during those same years the department hatched a plan to inspect 67 non-metal mines but since then has visited only 44 per cent of those.

The auditors write: “Department officials told us that they had stopped inspections on non-metal mines because they had found a high level of compliance.”

Yet, the auditors found Environment Canada “had no consolidated information about the overall non-metal mining sector… This lack of information made it difficult for the department to understand the overall non-metal sector and to carry out comprehensive risk analyses.”

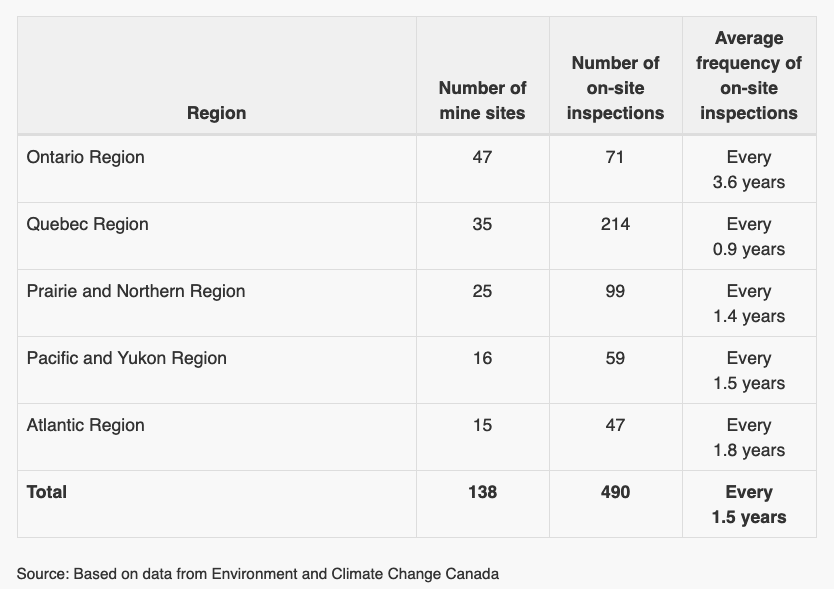

During the audit period, there were 270 on-site inspections of Canada’s 117 non-metal mines, an average of one inspection per mine every 2.4 years. This is lower than the average inspection of metal mines, which are inspected on average once every 1.5 years.

In a response, Environment Canada said it will develop a risk framework for both metal and non-metal mines by 2020.

Even though Environment and Climate Change Canada does monitor waste released from metal mines in Canada, the audit found the department did not specify which mine sites it had inspected.

“As a result, Canadians did not know how mining effluent might be affecting their community,” the report states.

“This finding matters because complete and accurate information on the environmental effects of mining effluent is important in assessing how well the regulations protect fish and their habitat.”

Ontario has the highest number of mines in all of Canada but received the lowest number of inspections from Environment Canada. The average frequency of on-site inspections for mines in Quebec are every 0.9 years, for the Pacific and Yukon regions every 1.5 years and for Ontario every 3.6 years.

The report also found that inspections are not tracked by mine site, but instead by company name, although companies may have several mine sites.

Mine inspections between January 2013 and June 2018. Source: 2019 Spring Reports of the Commissioner of the Environment

Reports generated from these inspections also contained incomplete information, enough so that auditors had to leave some mines out of their report “because of lack of data.” Inspectors also at times relied on company data but didn’t include “controls to ensure the accuracy of companies’ self-reported compliance data.”

Environment Canada responded to the report’s recommendation for better enforcement plans, saying it will “develop a more effective way to track data on metal and non-metal mines at the site” by 2021.

Environment Canada visited a mine site in 2007, 2012 and 2015 and found metal mining effluent was having a negative effect on the growth and reproduction rates of fish downstream.

Although the report notes the location of this mine isn’t specified (see above), the auditors found the circumstances were used to strengthen regulations by introducing “stricter limits for some substances that already had limits in place.”

The report notes: “Increased transparency is also important to support public confidence in government regulation of the mining industry.” Um, yeah.

Much of the metal mining that is permitted under Canada’s regulations causes harm to waterways and fish habitat. It’s difficult to avoid for projects that use so much water and create such significant amounts of contaminated waste. Many mine tailings ponds are built in or on top of ponds or rivers. (For example, Taseko’s rejected Prosperity Mine proposed using Fish Lake, an area treasured by the Tsilhqot’in First Nation, as a tailings pond.)

The report states that as of June 2018, mine waste was permitted to be dumped in 42 bodies of water, covering a combined surface area of 38 square kilometres. Note this doesn’t include tailings facilities for oilsands, potash or coal mines. There are more than 176 square kilometres of oilsands tailings, which have an estimated clean-up cost of $51 billion.

These giant tailings facilities and their impacts on fish-bearing waters is why, under metal mining effluent regulations, companies that harm fish habitat are required to compensate for that harm.

But the audit found Fisheries and Oceans Canada is often not monitoring companies to ensure their plans to offset fish harm are implemented and or effective. The department agreed, the report notes, stating a revised monitoring program will be implemented April 2020.

Between April 2014 and June 2018 mining companies were fined $16.6 million in penalties for violations under the Fisheries Act. The report found that in recent years there is a notable trend toward larger penalties.

However, the audit found that Environment Canada “did not track data on alleged violations by mines site . . . This meant that the department could not clearly pinpoint areas for follow-up.”

The report also notes that prior to 2017 the department wasn’t keeping clear track of where violations occurred and so couldn’t assess when repeat violations were occurring by mine site.

A metallurgical coal mine, owned and operated by Teck Resources in B.C.’s Elk Valley. Photo: Jayce Hawkins / The Narwhal

In 2016 Environment Canada reported a 94 to 99 per cent compliance rate for metal mines and their effluent limits.

However the audit found those rates were based on an incomplete data set, because 35 per cent of companies did not submit complete information on their liquid waste monitoring while other companies submitted no data whatsoever.

The audit also notes that Environment Canada’s reporting ”provided no information about spills and unauthorized effluent discharge . . . As a result, the department’s report lacked a complete picture of mining sites’ effects on fish and their habitat.”

“We also found that Environment and Climate Change Canada’s reporting was not up to date. For example, the 2016 status report on metal mine compliance was not issued until 2018.”

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On March 17, federal Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre...

Continue reading

The current trade war with the U.S. means Canada must confront whether its domestic food...

Residents and nearby First Nations wanted a new environmental impact assessment of the contentious project....

Growing up, Christian Allaire loved spending summers with his cousins in his grandma’s backyard, near...