Canadians have another facet of national defence right under our noses

The current trade war with the U.S. means Canada must confront whether its domestic food...

Four days into his job as premier, Doug Ford announced the end of Ontario’s $3 billion cap-and-trade climate program as his government’s first policy decision. Since then, the Progressive Conservatives have made dramatic changes to the province’s environmental policy. The changes affect everything from endangered species to renewable energy to development, and critics say most are harmful to wildlife and natural spaces, as well as counterintuitive given the scale of the climate crisis.

The government disagrees. “Ontario is a leader in clean, green growth in Canada and around the world, and our government takes environmental protection very seriously,” Andrew Kennedy, a spokesperson for the ministry of environment, said in an emailed statement to The Narwhal. “We are proud to lead Ontario at the front line of Canada’s climate change response.”

The Narwhal is tracking how Premier Ford and the Progressive Conservatives have shaped Ontario’s environmental policy landscape. This is our list from the government’s first term: for new updates since its June 2022 election victory, go here.

For three years in a row, the Ford government has come under fire from Ontario’s Auditor General for not following the province’s Environmental Bill of Rights, a law that requires the government to be transparent about environmental changes and gives citizens the right to weigh in.

In November 2021, Auditor General Bonnie Lysyk took her criticism one step further and accused the government of “deliberately” undermining its own rules.

Lysyk pointed to the Ford government’s decision to temporarily suspend key sections of the Environmental Bill of Rights during the first wave of COVID-19, saying it led to “less transparency and accountability.” The province also failed to abide by the Environmental Bill of Rights when it passed changes to environmental assessments without consulting the public.

In response, Piccini said the government is being transparent, and has worked to clear outdated notices from the online registry where it posts environmental changes for consultation.

“We have dedicated an educational webpage and ongoing public education campaign on the Environmental Bill of Rights, appreciate the Auditor General’s comments and are going to continue to take meaningful action,” he said.

The Ford government’s first year in office was marked by its dramatic cuts to spending for, well, pretty much everything. But the Progressive Conservatives made some of their largest cuts to environmental initiatives.

One huge move was to eliminate about 70 per cent of provincial funding for the Anishinabek/Ontario Fisheries Resource Centre, a non-profit that helps more than three dozen Indigenous communities protect endangered wildlife and natural resources. And as part of broader cuts to legal aid clinics, the government dropped its funding to the Canadian Environmental Law Association by 30 per cent. The association is a non-profit, public-interest law group. In 2019, the Progressive Conservatives also ended all financial support for the Ontario Biodiversity Council, a group of volunteer stakeholders and scientists who report to the public about the state of biodiversity in the province.

The Ford government also slashed the budget of the Ministry of the Environment, Conservation and Parks by about a third in 2019. Those cuts resulted in the Environment Ministry cutting the staff responsible for inspections and enforcement for hazardous spills by nine per cent, Ontario’s Auditor General found in November 2021.

The Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry, which also oversees some aspects of the environment, lost 14 per cent of its funding.

The Ford government has revived two major highway proposals that would carve through the protected forests, farmlands and wetlands of the Greenbelt. Both are old ideas that were dropped by previous governments.

Highway 413, which would connect the Toronto suburbs of Milton and Vaughan, is the most controversial. Also called the GTA West Corridor, it would harm 2,000 acres of farmland, cut through 85 waterways, damage 220 wetlands and disrupt the habitats of 10 species-at-risk. The former Liberal government axed the idea after a study showed the new highway would save drivers less than a minute. (The Ford government disputes this and said it would save drivers half an hour, but hasn’t shared any data to back up the figure.)

The other highway is the Bradford Bypass, which would connect Highways 400 and 404 north of Toronto. It would run through the Holland Marsh, a portion of the Greenbelt known for its sensitive wetlands and fertile soil.

The project last received an environmental assessment in 1997 — that review found the highway could pollute groundwater, surface water and the air. The Ford government has exempted both highways from undergoing another full review before construction begins.

Transportation Minister Caroline Mulroney has argued that the new roads would reduce pollution by eliminating emissions from idling cars stuck in traffic. Critics point to decades of research showing that new roads actually don’t resolve traffic problems in the long run, instead attracting new cars. In May 2021, after being asked by environmentalists, the federal government announced that it would do its own assessment of the Highway 413 proposal.

In July, Piccini launched a new youth environment council to give high schoolers a space to give input to the government on climate change and other key issues.

The council is a key project for Piccini, who said he was interested in ways to better engage young people when he was first appointed to his role as environment minister in June 2021.

“As the youngest environment minister in Ontario’s history I am excited to launch this new youth environment council to ensure our next generation are at the table to help find solutions to some of the most pressing environmental challenges of our time such as climate change and conservation,” Piccini said in a press release announcing the initiative. The move received praise from environmentalists and youth advocates.

Applications for the council closed in August 2021. Its members haven’t yet been announced, but Environment Ministry spokesperson Kennedy said Piccini is looking forward to meetings in 2022, and is planning them with COVID-19 safety protocols in mind.

In August 2019, without any warning, notice or consultation, the Ford government ordered the province’s 36 conservation authorities to “wind down” all activities that did not relate to their “core mandate,” though exactly what that meant was unspecified.

Unique to Ontario, conservation authorities manage local watersheds with the goal of protecting communities against flooding and erosion, and intervene in controversial development cases that propose to pave over wetlands and other natural habitats. The order to “wind down” came after the government cut provincial funding for natural hazard management by 50 per cent months earlier. The government said it would do a full review of all legislation that gave powers to these authorities with the intention of giving greater control to individual municipalities on issues of conservation.

The proposed legislation was tabled over a year after the order and passed in December 2020. It would gut conservation authorities’ ability to protect crucial waterways and wetlands, some of which run through the protected Greenbelt area around Toronto. The bill would shift the power of approval for development applications from local conservation authorities to the Minister of Natural Resources and Forestry. In response, seven members of the Greenbelt Council resigned, including chair David Crombie, a former Progressive Conservative MP and Toronto mayor.

In a surprising turn of events, the government created a working group that brought together developers, urban planners, agricultural representatives and two consecutive provincial environment ministers to discuss how best to implement the new regulations. Together, they seem to have mended a long-broken relationship.

After the Ford government’s move to take powers away from conservation authorities resulted in the resignation of seven members of Ontario’s Greenbelt Council in protest, the province needed to appoint a new chair. The man for the job, the Ford government decided, was retired Progressive Conservative MPP Norm Sterling.

It was a controversial move — not least because in 2005, Sterling voted against the creation of the Greenbelt. An environment minister in the PC government led by Mike Harris, Sterling was an MPP for 30 years, and has a nuanced legacy. He was resistant to implementing climate measures in the Kyoto Protocol and oversaw cuts to the environment ministry that were later found to have contributed to the Walkerton E. coli outbreak in 2000.

But he also helped write the Niagara Escarpment Plan, Canada’s first large-scale land conservation policy, and implemented Drive Clean, a since-cancelled program aimed at controlling emissions from cars and trucks. When he left politics in 2011, he garnered praise from across the aisle.

Sterling’s April 2021 appointment to the Greenbelt Council was met with concern from environmentalists and opposition parties. The council reports to Municipal Affairs Minister Steve Clark, who defended Sterling’s record.

“Mr. Sterling brings important experience to the Greenbelt Council, and I am confident that under his leadership there will be incredible work done to support growing the Greenbelt,” Clark said at the time.

On April 1, 2019, the federal government’s carbon price came into effect. That same day, the Ontario government cancelled what it described as the “outdated, ineffective” Drive Clean program. Introduced in 1999, this was a mandatory emissions test for light-duty passenger vehicles meant to identify and repair cars and trucks that polluted excessively. It was considered an important tool in curbing emissions from transportation vehicles, which account for over a third of the province’s greenhouse gas emissions. The program is credited with preventing 400,000 tonnes of pollutants, but as industry standards for vehicles improved, the Drive Clean program became less relevant, with a steady annual decrease in the number of vehicles that failed the test.

At the time that Ford’s then-environment minister, Rod Phillips, said the program had outgrown “its usefulness,” less than five per cent of the approximately two million vehicles tested annually failed. “It’s history, it’s done, it’s gone,” Ford said, adding that the move would save taxpayers more than $40 million a year and “end hours of frustration and wasted time caused by unnecessary tests.” Heavy diesel commercial motor vehicles continue to require an emissions test, but the government was criticized for not introducing another program that would seriously address the majority of Ontario’s transportation emissions.

As of December 31, 2021, the Toxics Reduction Act will no longer be in place. Along with the federal National Pollutant Release Inventory Program, the 2009 legislation was designed to curb the use, creation and release of toxic substances in specific sectors to voluntarily develop toxics reduction plans and report yearly.

According to the Ford government, the Toxics Reduction Act was “ineffective and has not achieved meaningful reductions.” That’s not true: according to a 2017 Minister of Environment and Energy report on Toxics Reductions, between 2015 and 2016 the legislation contributed to a seven per cent decrease in the use of toxic substances, a nine per cent decrease in the amount of toxic substances contained in products between 2015 and 2016, and a two per cent reduction of toxic substances released in the environment.

Despite that, the act was repealed in April 2019 by the passage of an omnibus “Open for Business” bill aimed at “reducing regulatory burdens in 12 sectors.”

Another casualty of the Ford government’s 2019 budget was $4.7 million in annual funding allotted to the 50 Million Tree Program run by the non-profit Forests Ontario. The goal of the program was to plant 50 million trees by 2025. The program subsidized the costs of planting individual trees as well as creating brand new forests, to encourage communities and private landowners to do so. In 2019, Forests Ontario reported that the program contributes $12.7 million annually to Ontario’s GDP, creates more than 300 full-time seasonal jobs and captures and removes 19,000 tonnes of carbon every year. New forests provide other benefits, such as improving biodiversity and creating recreational opportunities.

The Ford government argued the funding wasn’t being used well, finding that in the 11 years since its inception, Forests Ontario had planted only 27 million trees: the group responded that funding hadn’t increased with the rising costs of planting. The government also noted that the forestry industry had planted over a million trees since 2005, to which Forests Ontario, responded that logging companies were legally obligated to replant what they cut.

According to Forests Ontario, the non-profit organization that administers the program, the provincial government funded tree-planting in southern Ontario for more than a century until Ford came to power. Fun fact: before the Progressive Conservatives formed government, Tory MPP Ted Arnott wanted to triple the program’s goal at one point and plant even more trees. As speaker of the legislature, he couldn’t object when the budget to cut the program was passed.

The program was temporarily saved when the federal government committed to a $15-million investment over four years, enough to plant 10 million more trees.

After coming into power in 2018, the Ford government scrapped an existing buyer incentive program, which provided up to $14,000 on the purchase of an electric vehicle. (For comparison, buyer incentives exist in eight provinces and territories.) Ford also removed a $2.5 million incentive program that helped homeowners install their own charging equipment. The government also deleted electric vehicle charging station requirements in Ontario’s building code and ripped out a couple dozen public electric vehicle charging stations that had already been installed.

Since November 2020, the government has shifted gears — pressured by a series of industry shifts including charging station projects from provincial power companies and utilities and efforts by major automakers to retool assembly plants to exclusively build electric vehicles.

Phase Two of the government’s Driving Prosperity pledges to meet four key targets by 2030: “reposition vehicle and parts production for the car of the future, establish and support a battery supply chain ecosystem, innovate in every stage of development, invest in Ontario’s auto workers.” The plan states the government’s goal is to see 400,000 electric vehicles manufactured in the province in the same time frame and also establish a new electric vehicle and hybrid assembly plant. The plan also relies heavily on taking advantage of critical minerals found in the Ring of Fire, which has spurred questions about the economic and social welfare benefits to First Nations communities in the region.

The climate change impact assessment is a key part of the province’s 2018 Made-in-Ontario Environment Plan. As a first step, in 2019, Ontario established an advisory panel to provide the minister of the environment, conservation and parks with advice on the implementation of the province’s climate change actions. The two-year assessment itself formally began in August 2020 with the goal “to better understand where and how climate change is likely to affect communities, critical infrastructure, economies and the natural environment, while helping to strengthen the province’s resilience to the impacts of climate change.”

The assessment will be led by the independent Ottawa-based non-profit Climate Risk Institute, who will review climate data, land use patterns and socio-economic projections, and also consult Indigenous communities, municipalities, the public and “key economic sectors” in the process. Results are expected in 2022.

Right after taking office in the summer of 2018, Ford sent out a press release announcing the end of cap-and-trade: he inaccurately deemed it “government cash grabs,” when, in fact, the funds collected were largely earmarked for other climate-related projects. The program allowed companies to buy and sell credits to pollute, the idea being that the added cost would incentivize businesses to pollute less. Nobel-prize winning economists William Nordhaus and Paul Romer, as well as much scientific research, tout the cap-and-trade program as the most cost-effective and efficient way to reduce greenhouse gas emissions that contribute to global heating.

The emissions-trading scheme has often been mischaracterized as a “carbon tax” by members of the Ford government. On Oct. 31, 2018, the legislation killing cap-and-trade passed, MPP Sam Oosterhoff led the PC caucus in a cover version of “Monster Mash:” “We stopped the tax/We stopped the carbon tax,” he declared in a spooky voice. In the summer of 2019, the government introduced mandatory stickers for all gas pump operators that said “the federal carbon tax will cost you:” the proposed fine for not displaying them was up to $10,000 a day. The stickers showed the federally-mandated carbon price adding 4.4 cents per litre to the price of gasoline, but did not include information about available rebates or the costs associated with rising emissions. In 2020, the Ontario Superior Court of Justice deemed the stickers unconstitutional following a Canadian Civil Liberties Association challenge.

The decision to end cap-and-trade spelled the end of a $100 million budget for school repairs, a $337 million Green Ontario Fund that offered people rebates to retrofit their homes and businesses with energy-saving technologies, and 227 clean energy programs that included 120 commuter cycling programs in 120 jurisdictions across the province, 41 sustainable social housing programs and 20 retrofit projects for social housing apartments.

In October 2019, Ontario’s Superior Court determined the Ford government acted illegally when it killed the program without first carrying out the required public consultations. Earlier this year, the Ford government lost again in the Supreme Court of Canada when it challenged the federal government’s efforts to implement a carbon price in the absence of Ontario having its own pollution pricing program. In the wake of that decision, the province has introduced a weak carbon pricing standard that sets pricing thresholds by facility, not industry.

A week after ending the cap-and-trade program, the Ford government cancelled 758 renewable energy contracts, including hydroelectric, solar and wind farms that were mid-construction. The first to be axed was the White Pines Wind Project in Milford, Ont., which was 10 years in the making and characterized by Ford as “those terrible, terrible wind turbines.” The second was the Nation Rise wind farm in North Stormont, Ont. In May 2020, a court overturned the province’s decision and allowed construction of the project to resume.

The complete list also included solar rooftops on schools, libraries, community and municipal buildings. Then-Energy Minister Greg Rickford said the cuts would save provincial ratepayers $790 million, a figure industry officials disputed and said would disproportionately hurt local and First Nations communities. The PC government spent more than $230 million to cancel these projects, a decision Ford said he was “proud” of.

In an Oct. 29, 2021 statement to The Narwhal, Palmer Lockridge, a spokesperson for Ontario’s minister of energy, said these “wasteful” contracts “would have driven up electricity bills, not only making life more expensive, but also hindering other progressive actions to reduce emissions such as electrification which benefit from affordable electricity rates.” He said the government is working on “a range of initiatives informed by feedback through the environmental registry.” This includes a project in London that explores “how a community can work together to generate renewable energy, protect the environment and lower electricity costs.”

In April 2021, the Ford government introduced a bill that would deprioritize renewable energy by repealing measures that made it easier to build new clean power projects. The province said it’s “no longer appropriate” to prioritize clean energy because “Ontario has built a clean energy supply.” Kennedy, spokesperson for the minister of environment, said the government will release the province’s low-carbon hydrogen strategy “soon.”

Most of Ontario’s electricity comes from emissions-free hydro-electric and nuclear power, which makes for a relatively clean system — the province does use some natural gas, but the fossil fuel makes up a small portion of the mix. In 2020, however, the province spent $2.8 billion to buy three natural gas plants that the Ford government is planning to fire up more often over the next decade as nuclear plants go offline for refurbishment — a move that could erase a third of the emissions reductions Ontario achieved by phasing out coal.

There is a need to find new energy sources as Ontario’s aging nuclear plants go offline for refurbishment, and gas plants can fire up quickly to meet sudden demand, such as during summer heat waves. Ontario’s Independent Electricity Systems Operator has said in the past that the province needs the plants to maintain flexibility, and was even more frank in a report released Oct. 7, 2021 stating that it wouldn’t be feasible to phase out gas plants by 2030 while meeting the province’s energy needs. Critics say the government should be focused on renewable energy sources instead.

In the fall of 2018, on the 25th anniversary of the creation of the position, the Ford government eliminated the office of the environmental commissioner, an independent provincial watchdog that held the government accountable on its environmental actions or inactions. The position was created under the Environmental Bill of Rights, and tasked with monitoring the government’s compliance with environmental laws and reporting annually on the government’s progress on its greenhouse gas reduction targets. The position was then, and last, held by Dianne Saxe (now a Green Party of Ontario candidate), who revealed that over 1,300 tonnes of sewage had been dumped into Ontario waterways in 2017 just days before her office was axed.

The bill of rights also allowed any two Ontario residents to apply to the commissioner’s office to ask it to review any law, regulation or decision by the government pertaining to the protection of the environment. That accountability mechanism was stripped, just as the Ford government was enacting one environmental cut after another. Now, those appeals go directly to the Minister of Environment, Conservation and Parks and some of the accountability work of the environment commissioner’s office has been folded into the office of the auditor general. The government did not provide The Narwhal with an update on how the new appeal process is working.

In June 2021, Ford’s then-environment minister Jeff Yurek finalized a massive rewrite of Ontario’s recycling program, into what environment ministry spokesperson Kennedy describes as a “common sense new blue box program with the highest diversion rate targets in North America” that “will save taxpayers money, keep recyclables out of landfills, and deliver standardized services to all corners of the province, including First Nations.”

The new rules, to be phased in from 2023 to 2025, standardized the process across the province — before, it happened through more than 250 local programs, each with different specifications. The changes also mean companies that produce plastic must fully pay for recycling programs, shifting costs away from municipalities.

Municipalities and the recycling industry praised the rewrite, which allows more materials to be recycled and for blue box services to be expanded to rural communities, apartment buildings, long-term care homes, schools and municipal parks. Standardizing the system could save an estimated $156 million annually, the province said. Environmentalists said they were concerned the new program’s targets weren’t high enough.

The Ford government has watered down protections for endangered species twice. The first set of changes, included in the omnibus Bill 108 — dubbed the More Homes, More Choice Act — were aimed at making it easier for the development industry to pursue projects even if they would likely harm species at risk. The legislation, passed in May 2019, allows the province to delay protecting endangered species, weakens protections for species with populations outside of Ontario, opened up the chance for non-scientific experts to join the provincial committee that classifies species at risk, and eliminated a requirement that the environment minister consult an independent expert on how certain actions could affect endangered species. It also created a “pay to slay” fund, officially known as the Species at Risk Conservation Trust, that would allow developers to destroy key habitats if they pay fees, which are meant to be used to help the species recover elsewhere.

Kennedy told The Narwhal that the trust, and the agency that oversees it, “will have the expertise to invest in strategic, large-scale, and co-ordinated actions to support positive outcomes for certain species at risk.” Environmentalists disagree: the charity Ontario Nature argues it gives developers “free rein to bulldoze, dig up, cut down and pave over the habitats of our most vulnerable plants and animals.”

The next year, in June 2020, the Ford government extended a long-running rule that exempts forestry companies from abiding by Ontario’s Endangered Species Act. Instead, those companies follow a logging-specific set of rules that attempt to minimize the impact industrial activity could have on species at risk, but do not support their recovery.

Ontario isn’t collecting enough data to know whether it is actually conserving endangered species, Auditor General Bonnie Lysyk found last year. The same report also found that many of the provincial plans governing protected lands didn’t include measures to safeguard endangered species — even though those areas are home to three-quarters of Ontario’s species-at-risk.

In another move that happened a matter of days after he was sworn in, Ford fired Ontario’s first chief scientist. Dr. Molly Shoichet, a biomedical engineer who teaches at the University of Toronto, had been in the role for six months. The previous Liberal government had meant for the chief scientist to advise the government, and to make sure all of its relevant policy decisions were rooted in science.

At the time, Ford’s office said it was seeking a “suitable and qualified replacement.” Shoichet told The Globe and Mail she believed it wasn’t about her, “but rather an out-with-the-old and in-with-the-new” decision. As of Oct. 2021, the role has not been filled. The government did not respond to a request for information on why she was fired and when the position would be filled.

In July 2020, the Ford government passed Bill 197, legislation meant to facilitate economic recovery from the devastation of COVID-19. Buried in the bill was a major overhaul to Ontario’s environmental assessment law. Environmental assessments are pivotal to development proposals, helping the government determine whether a project might have negative impacts on surrounding green space, wildlife and watersheds. At the time, Ford said “we aren’t going to dodge” the process, but make it “quicker and smarter.”

Critics say the bill actually made the regime tremendously weaker. Public-sector projects used to be subject to environmental assessments automatically — now proposals only need one if the government decides it should take place. Citizens also used to have a mechanism to ask the environment minister to conduct a full assessment on projects that would otherwise be exempt, but Bill 197 eliminated that possibility.

The Ford government passed the bill before consulting the public, which Lysyk said was “not compliant” with rules in Ontario’s Environmental Bill of Rights. The province is writing a list to guide decisions about whether environmental assessments are needed.

Kennedy wrote the government is “grateful” to Lysyk “for her shared goals for Ontario’s actions on climate and the environment; she and her team have been more than capable with respect to accountability and oversight.” He added: “oversight is also at the heart of our environmental assessment program, which supports strong environmental oversight and focuses resources on high-impact projects.”

As the first wave of COVID-19 took hold in Ontario, the Ford government dramatically ramped up its use of a special land zoning power called an MZO, or minister’s zoning order. The directives allow the ministry of municipal affairs, now headed by Steve Clark, to decide how a piece of land can be used, overriding the local planning process and any existing zoning to clear the way for a project to go ahead. The orders cannot be appealed. Up until 2018, governments tended to use them for emergency situations: in 2012, when the Liberal government headed by Dalton McGuinty used an MZO to relocate a grocery store in Elliot Lake, Ont. when the town’s only one was destroyed by the collapse of a mall roof.

Ford’s government used five in 2019 — which Clark followed up by issuing 32 of the orders in 2020, more than twice the number the previous Liberal government issued over its 15 years in power. He’s issued 19 so far in 2021. The PC government has also twice strengthened its minister’s zoning order powers through legislation. The province has said it only uses MZOs on provincially-owned land, or at the request of municipalities.

In a statement, Zoe Knowles, spokesperson for the Ontario minister of municipal affairs and housing, said MZOs “are an important part of our government’s policy toolkit to help critical local projects located outside of the Greenbelt move at the pace Ontarians need and deserve.”

“It’s important to remember that an MZO kick-starts the zoning process by ensuring red tape does not get in the way of much-needed local projects,” Knowles wrote, adding that municipalities have final say on development plan approvals, permits and more. (While this is true, any amendments to Greenbelt designations must be approved by the province.) “It is our expectation that municipalities do their due diligence and to conduct proper consultation in their communities, including with conservation authorities and other impacted stakeholders.”

Knowles also said the government has pledged not to issue MZOs for developments on the Greenbelt, but in fact, Clark did approve an MZO for provincially-owned Greenbelt land in Aurora, Ont., which allowed for more intense development. The government has also committed to add two acres to the protected zone for every acre provincewide that is developed through an MZO, Knowles said.

In many cases, the government has used these orders to override environmental concerns: 14 times from 2019 to 2020, an analysis by National Observer found. That included a case where an MZO allowed developers to pave over a protected wetland to build a Walmart warehouse in Vaughan, Ont. In several other cases, the orders have opened up farmland for development — a trend critics say is concerning because it contributes to urban sprawl, often eliminating green space that acts as a carbon sink or lessening Ontario’s ability to grow food locally.

Ontario isn’t taking its 2030 climate targets seriously enough, Lysyk warned in Nov. 2020. In an audit, her office found that the Ford government had not made emissions reduction a “cross-government priority” and is not reducing emissions from fossil fuel-use in buildings, the province’s third-largest source of greenhouse gases. Under the Paris Agreement, Ontario must reduce its emissions to 30 per cent below 2005 levels by the end of the decade.

At the time, Yurek said the government was still committed to the goal, but it would be a “difficult path to go forward” and that Ontario has a “long way to go.” The government did not respond to The Narwhal’s request for comment on this.

The words “excess soil management” aren’t exactly the most thrilling. But the dirty issue of what to do about leftover soil excavated from construction sites is one that has caused more than a few dust-ups in Ontario’s recent history.

In many cases, construction of shiny new condo towers requires multi-storey parking garages that are dug into the ground. Some of the dirt coming from such sites is clean and can be re-used. But some is contaminated.

In 2014, a Toronto Star investigation showed booming construction in the city was digging up huge amounts of contaminated soil, and the Ontario government was failing to properly track where the dirt was dumped. Experts warned that the pollution could harm prime farmland, including some in Ontario’s Greenbelt. The Liberal government of the day launched a review looking at the need for a provincial policy and released a draft regulation in 2018, but conflicts over the crud continued.

In 2015, the Township of Scugog, about an hour’s drive northeast of Toronto, said it would no longer allow the dumping of 200 truckloads per day of soil on a private site after it discovered samples of the dirt were contaminated with lead and benzene. In Hamilton, a lawsuit filed in 2021 alleged that the municipality conspired with a since-slain mobster to dump thousands of loads of dirt on a rural property in 2018. The claims of the suit, which haven’t been tested in court, allege the soil was contaminated with mercury and other chemicals that cause cancer. The City of Hamilton has denied the allegations.

In 2019, the Progressive Conservative government passed revamped regulations around soil disposal. The new rules, which began coming into effect last year, require developers to register the amount of soil being moved from construction sites and where they plan to put it. Developers also must test the dirt for contaminants and report the results. The regulation also barred clean soil from being sent to landfill and included standards for re-using the dirt.

The government said the changes would make it easier for soil to be used again, instead of having developers pay to dump it, and increase accountability for those moving contaminated dirt. The news was met with praise from local officials in Hamilton, and residents near the contaminated site now at the centre of the lawsuit.

Though the second round of changes was supposed to kick in on Jan. 1, 2022, the province has proposed pushing that back a year to give industry more time to understand the rules.

The Ford government’s pursuit of minerals in the Far North of Ontario is shaping up to be a major election issue in 2022. It was in 2018 too — back then, Ford pledged to build access roads to mineral deposits in a remote region of the Hudson Bay Lowlands, the Ring of Fire, even if he had to hop on a bulldozer himself. (He’s the latest in a long line of Ontario politicians to make similar promises; none have succeeded so far.)

The Ring of Fire is still a major part of the equation. But on March 17, the Progressive Conservative government also released its broader Critical Minerals Strategy, a five-year plan aimed at capitalizing on growing demand for minerals like nickel, cobalt, lithium and platinum. These are crucial in clean technology like electric car batteries, tying in with the Ford government’s about-face on electric vehicles.

Some key deposits are in the Ring of Fire, though the value is unproven. But other deposits elsewhere in the province are being mined already.

In the strategy, the government outlines a roadmap to boost mining, already a huge industry in Ontario, and mineral processing at manufacturing facilities in the south, which it says could add $3.5 billion to the province’s economy. It also earmarked $29 million in funding to support junior mining companies doing exploration, and to create a fund to support research on extraction and processing in the north.

But the path forward may not be so smooth, especially when it comes to the Ring of Fire. There are no permanent roads to the remote region, which also lacks basic infrastructure. It would take an estimated $1.6 billion to construct an access road over the boggy peatlands, which are difficult to build on, and although the Ford government has touted past provincial investments, it still hasn’t secured the federal funds that it says would make the project possible. The federal and provincial governments are working together on several impact assessments for the region that are slated to take years.

The Ring of Fire’s rich peatlands are a huge carbon sink — disturbing them would have worrying implications for the fight against climate change, and could harm wildlife habitat and downstream communities.

At the same time, many First Nations communities in Ontario’s Far North are coping with the overlapping crises of COVID-19, poverty, youth suicides and decades-old boil-water advisories. Nations near the Ring of Fire don’t agree on the best way forward and whether access roads or mining should be part of it.

Marten Falls and Webequie First Nations are backing efforts to build access roads, saying the infrastructure could help improve the quality of life in their communities.

In April 2021, Attawapiskat, Fort Albany and Neskantaga First Nations raised concerns about the assessment process, declaring a moratorium on development in the Ring of Fire until the provincial and federal governments ensure First Nations have a fair say and can fully examine how development will affect the region. Neskantaga also filed a lawsuit against the Ontario government in November 2021, asking a court to “create ground rules” for consultation with Indigenous communities in a meaningful way.

CBC has reported that lawyers and advocates for First Nations in northern Ontario have raised red flags about the Critical Minerals Strategy, saying they’re worried the province is pushing forward without consulting Indigenous communities and tackling environmental concerns.

When asked by CBC about conflict between the new strategy and environmental concerns around mining, Northern Development, Mines, Natural Resources and Forestry Minister Greg Rickford pointed instead to the potential environmental benefits of clean technology.

“Without mining there is no such thing as a green economy,” Rickford said. “Without those critical minerals, you will not be able to drive a clean, green automobile of the future.”

The Ford government has been steadfast in its vision for a car-based future throughout its four year term — prioritizing roads even as it invests in transit. In March, Ford dropped a massive $82 billion transit and transportation plan for the next two decades that mentions “bus service” only six times, versus 107 mentions of “highway.” It’s a ratio that has been consistent throughout Ford’s tenure: he has expanded highways with a promise of unclogging congestion and scrapped highway tolls on two roads in Durham Region, east of Toronto, all in an effort to win over drivers across the province. “We’re pouring money into infrastructure, making sure that people get from point A to point B,” Ford said in announcing the plan. “People don’t want to be sitting in gridlock, we’re going to make sure we continue building highways and roads and bridges.”

Onlookers say the right solutions are not being engaged to reduce gridlock or move people faster. For example, in February, the Ford government announced it was returning $1 billion to the province’s more than 8.3 million drivers by cancelling licence plate renewal fees. Economists and transit users alike say this money could have funded temporary reductions in transit fares and increased rapid bus service lanes, which cost less than $100 million to implement.

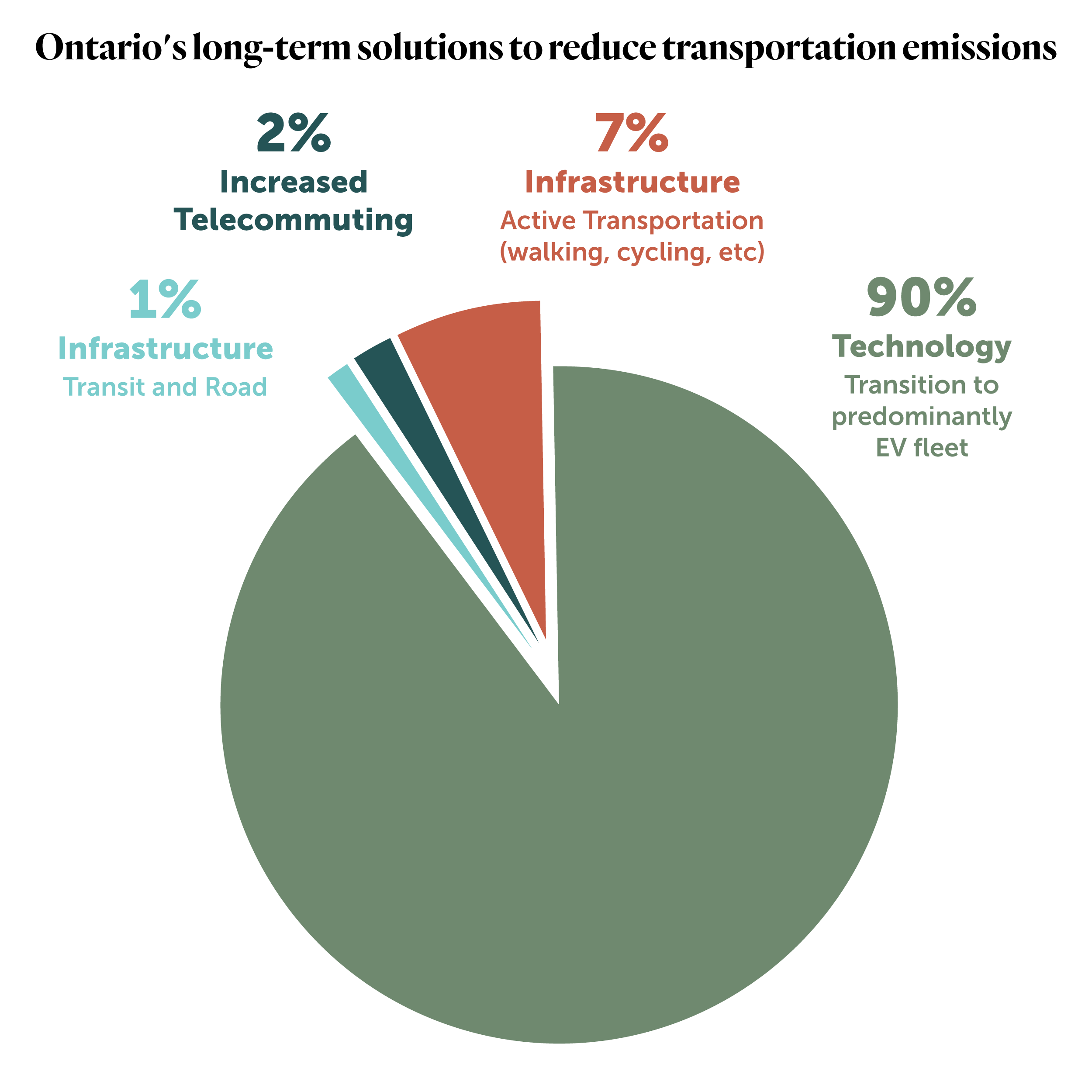

While the government did announce $28 billion for four new transit lines in Toronto and one in Hamilton, and extended GO Train commuter services, these projects are mostly underground so that they don’t take away from car lanes, and will take decades to build. These transit projects are also not a major element of the Ford government’s plans to reduce transportation emissions, the largest source of emissions in Ontario. According to their new transportation plan 90 per cent of these reductions will come from transitioning to electric vehicles by 2051 — the new look of Ford’s car-based transportation future.

It’s been 15 years since the last revisions to Ontario’s elementary school science curriculum, so it’s about time for a new one. The Education Ministry released it at the beginning of March, saying in a press release that the goal is to align public school students’ education “with the province’s economic needs.” As outlined, that means a heavy focus on coding, artificial intelligence and other computer sciences, as well as lessons on how science is relevant to daily life, especially for students considering the skilled trades.

While technology is unquestionably the focus, the new elementary curriculum is more detailed than the last in its consideration of environmental stressors. Climate change is a specific area of study across grades — lessons are meant to be age-appropriate and explore mitigation as well as causes, as well as impart “hope and optimism” while helping students figure out “how they can make the most environmentally responsible decisions possible.” There is also an overarching emphasis on “food literacy”: students in grade 3 are meant to discuss the “benefits and limitations” of local food, while the Grade 7 curriculum will explore how different forms of agriculture interact with various ecosystems.

The new curriculum also reflects the Ford government’s current approach to education about Indigenous people and practices, an area that it has been criticized on during its tenure. Soon after the Progressive Conservatives came into power in 2018, summer meetings about revising the curriculum to include Indigenous language instruction and other updates recommended by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission were cancelled. Then, last fall, the Education Ministry promised to strengthen lessons on Indigenous topics for Grades 1 through 3 citing the Truth and Reconciliation Commission as a reason.

Throughout the elementary grades, the new science curriculum makes multiple mentions of First Nations, Inuit and Métis ideas and communities. Starting next September, students in Grade 6 are meant to learn about the effect of “electrical energy generation” technologies, including on First Nations, Inuit and Métis communities; notably, a number of First Nations in Ontario are unhappy with proposals for long-term disposal of nuclear waste on their territories. By the end of Grade 8, students are meant to “demonstrate an understanding of First Nations, Métis and Inuit knowledges and values about water, connections to water and ways of managing water resources sustainably.”

While changes to the Grade 9 curriculum were announced at the same time, at press time they were not detailed on the Ministry of Education’s high school curriculum website.

Whether you love it or hate it, Ontario’s Official Day of Action on Litter has become a flashpoint for critics of the Ford government’s environmental policies.

In October 2019, the Ford government designated the second Tuesday of May an annual litter clean-up day. But so far, the “action” part hasn’t actually happened — both in 2020 and in 2021, Ontario was under stay-at-home orders due to COVID-19 for Litter Day, meaning no in-person clean-ups were possible. (Between lockdowns, MPPs have participated in other local litter clean-up days.)

“These are extraordinary times with our focus entirely on staying safe and stopping the spread, but we must never forget the importance of preserving our environment,” a government press release quoted then-environment minister Jeff Yurek as saying in 2020.

“When the time is right, our government will work with communities and our partners to organize litter clean-up days across the province.”

In 2021, under lockdown again, the government changed focus: Yurek said the event would be focused on “raising awareness of the impacts of waste in the environment.”

The Progressive Conservatives have touted Litter Day as proof the government is delivering on pledges in its much-criticized climate plan, which promised to keep parks and waterways clear of waste.

Critics have said the day of action perpetuates the myth that individuals alone can fix larger systemic issues with single-use plastics and other consumer pollution. They also say the annual events fail to make a difference when the government is rolling back other environmental protections.

“We do have Litter Day, but we don’t have a credible climate change plan,” Ontario NDP environment critic Sandy Shaw said at Queens Park last October.

The Ford government announced plans to expand Ontario’s Greenbelt in early 2021. Later that year, it pledged to add two acres of land to the protected area for every acre developed using Minister’s Zoning Orders, a controversial power that allows the province to fast-track projects without holding public consultations.

But when the government announced an updated version of its Greenbelt expansion plan in spring 2022, it was a pared-down version that didn’t appear to deliver on the land-swap pledge.

Originally, the Progressive Conservatives had suggested including the Paris-Galt Moraine, a rock formation to the west of Toronto. But the government dropped that plan — and also said it had faced pushback on it from developers and the aggregate sector.

The new additions are instead a series of urban river valleys, all already having some level of protection. The government wouldn’t say how many acres it encompasses, so it’s unclear whether it’s enough to make up for the province’s dozens of Minister’s Zoning Orders. But on a map, the proposed additions look relatively small.

The Progressive Conservatives said they were still exploring ways to grow the Greenbelt more in the future.

In June 2020, the Ontario government rewrote the Growth Plan for the Greater Golden Horseshoe, the master document guiding how municipalities plan to use their land in the Greater Toronto Area, Hamilton and Niagara. These weren’t minor tweaks — the changes have led to a series of battles with municipalities over the push and pull between greenspace and development.

The new document asked municipalities to plan an extra decade ahead of what’s customary, tasking them to set aside land for the next three decades of expected growth. With the region changing so quickly, it’s very difficult to predict what cities will need in 30 years, critics said. The updated growth plan also included population projections that critics said were overinflated, and leaned heavily towards single-family homes with big footprints over denser developments, like mid-rise apartments. The Ford government has said it’s working to increase southern Ontario’s supply of housing and to deliver the types of homes it believes people want.

The result: some municipalities have said it’s difficult to follow the new rules without opening up farmland and greenspace for development — which is controversial because farmland, like greenspace, is an important carbon sink that also plays a vital role in local ecology and food security. Halton Region and the City of Hamilton have decided to push back, choosing to freeze their urban boundaries in place and accommodate new growth by making their communities more dense. Peel Region, however, voted to expand its urban boundaries by over 10,000 acres.

In January 2021, Energy Minister Todd Smith asked the Independent Electricity System Operator, the Crown corporation that runs Ontario’s electricity market, to “assess options” for a voluntary clean energy registry. This registry would allow for the sale of clean energy credits, a carbon offset scheme, that could be purchased by corporations or governments looking to meet their emissions-reduction targets. According to the minister’s directive, the money would subsidize electricity prices.

The scheme is trying to create a market that takes advantage of Ontario’s 94 per cent emissions-free grid. According to experts, there are few climate rewards from this scheme unless the money is reinvested in expanding clean energy projects and other emissions-reduction efforts.

The Narwhal learned that a version of this scheme was already in place: Ontario Power Generation, the province’s largest power generator and a Crown corporation, has been selling versions of clean energy credits outside of a government-approved framework since 2013. But many in the industry, including other clean energy generators that don’t currently have access to this revenue stream, say they weren’t aware of the program until earlier this year.

The proposal is a sharp turn for the Ford government, which has already spent $230 million to cancel renewable energy projects, including a $100 million wind farm. It also cancelled a $3 billion cap-and-trade program that could have generated a market for such credits.

The Ford government’s first and only climate plan — the 2018 Made-in-Ontario plan — proposed the creation of a $400 million carbon trust aimed at encouraging companies to invest in clean technologies and low-cost emissions-reduction initiatives. The trust was meant to account for four per cent of the government’s overall emissions reductions and “unlock over $1 billion of private capital.”

But the Ontario Carbon Trust never manifested. It was never mentioned again, whether in successive budgets or climate-related communications, including the Progressive Conservative’s latest emissions-reduction plan (which they say is not a plan). An independent board was meant to be set up to form the trust but never was.

When asked, a Ministry of Finance spokesperson told The Narwhal the trust is still in the works under a different name. “The Ministry of the Environment, Conservation and Parks continues to consider the design and mandate of the Emissions Reduction Fund (previously described as the Ontario Carbon Trust),” the spokesperson said. The Narwhal is awaiting more information.

In September 2018, the Ford government released a provincial forestry plan that would double logging volumes across Ontario’s 71 million hectares of forest — an area equivalent to Germany, Italy and the Netherlands combined — by 2030.

“Ontario is utilizing only half of the wood that it could sustainably harvest,” the 36-page provincial strategy said. Citing an increase in demand for multi-family homes and sustainable highrises, the plan said more logging could create new jobs in the sector.

Soon after taking office, the Progressive Conservative government announced a plan to connect more Ontarians to the network of natural gas pipelines for heating. The first two phases of the Natural Gas Expansion Project will connect nearly 18,000 more homes and businesses: projects mostly span southern Ontario, including several First Nations, as well as a smattering of locations in the north. The vast majority are being carried out by Enbridge Gas.

The cost of the expansion project is being spread among existing gas users through a $1 monthly charge and new customers through a surcharge of 23 cents per cubic metre of gas. That’s in addition to a $1.7 million grant from the Ontario Energy Board, the regulator of natural gas and electricity in the province, and $234 million from the province for phase two specifically.

Switching from furnace oil or propane will, according to Enbridge, save customers more than half of their heating costs.

Back in 2018, the project pitch was all about cost savings. “By cancelling the cap-and-trade carbon tax, we have already acted to bring natural gas prices down for Ontario families and businesses. Now we are taking the next step to ensure that the benefits of natural gas expansion are shared throughout the entire province,” Doug Ford said at the time. He didn’t mention that funds from cap-and-trade were earmarked for retrofit projects to reduce gas consumption, and therefore customers’ bills.

At the same time as this expansion, the province is also exploring natural gas reduction options. In the April budget, the Ford government announced a pilot project to install electric heat pumps in homes in a few cities, which “would be expected to reduce a household’s natural gas consumption by up to 40 per cent and greenhouse gas emissions by up to 30 per cent,” according to Ontario Energy Minister Todd Smith.

That’s not necessarily true, however: since Ford slashed renewable energy projects early in his tenure, the trajectory of Ontario’s electricity grid means that, in the future, those heat pumps could be running off natural gas.

— With files from Denise Balkissoon and Elaine Anselmi

Updated Dec. 20, 2021: This article was updated to add new items. Updated March 24, 2022, at 7 a.m. ET: This article was updated to include items 22 to 26. Updated May 25, 2022 at 9:45 a.m. ET: This story was updated to include items 27 to 32. Updated March 14, 2023 at 11:10 a.m. ET: This story was updated to correct the year the Ontario government passed legislation affecting conservation authorities.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On March 17, federal Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre...

Continue reading

The current trade war with the U.S. means Canada must confront whether its domestic food...

Residents and nearby First Nations wanted a new environmental impact assessment of the contentious project....

Growing up, Christian Allaire loved spending summers with his cousins in his grandma’s backyard, near...