The site of an infamous B.C. mining disaster could get even bigger. This First Nation is going to court — and ‘won’t back down’

Xatśūll First Nation is challenging B.C.’s approval of Mount Polley mine’s tailings dam raising. Indigenous...

Cabinet came first. Nearly all of Ontario Premier Doug Ford’s ministers marched solemn-faced through a parking lot across from a Margaritaville restaurant in Niagara Falls on Sept. 21, lining up a few paces back from the microphone.

Then came the premier, looking weary, casting a long shadow on the pavement.

“I made a promise to you that I wouldn’t touch the Greenbelt. I broke that promise, and for that I am very, very sorry,” Ford said.

It had been a mistake, he said. They — the premier, the ministers standing behind him who voted on the idea, the staffers who carried it out — moved too quickly. Over two days of meetings at their Niagara retreat, the cabinet had talked it over. And now, Ford promised, the whole thing would be undone.

“We’re putting this land back in the Greenbelt.”

It was a stunning reversal for the premier, who squinted in the afternoon sunlight as he spoke. It was also a far cry from where the story of Ford and the Greenbelt really began: a closed-door campaign event five years ago, where Ford had floated his plan to allow developers to build on parts of the protected land. Where his audience — men in suits, mostly, as seen in a grainy, now-infamous video of that night — applauded the idea, nodding their heads at the prospect.

It felt even further still from where Ford and his Progressive Conservatives had been a year earlier. Fresh from a dominant re-election, looking like a government with a stash of political capital to spend. But the unravelling started not long afterwards.

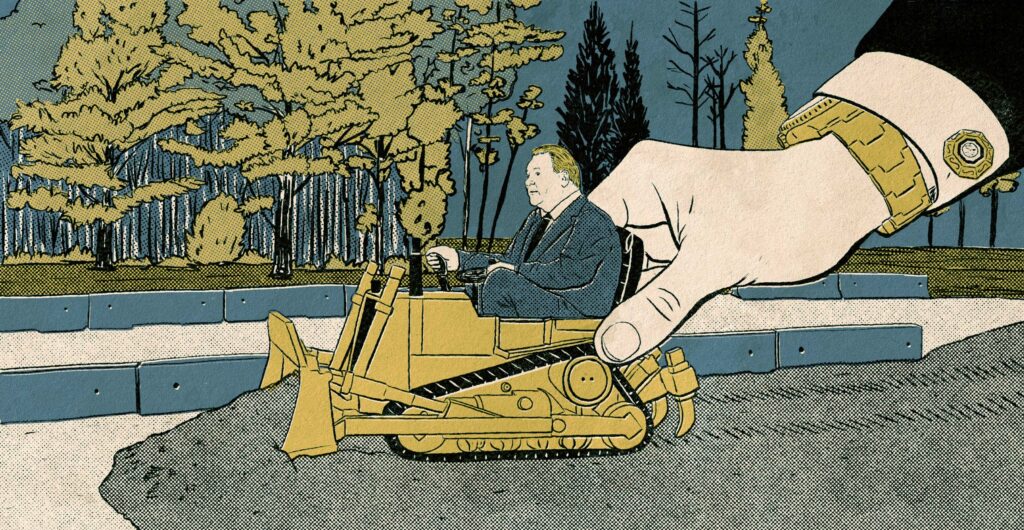

Through fall 2022, the government embarked on a chaotic campaign to carve out pieces of the Greenbelt, a beloved and protected ring of forests, farmland and waterways around the Greater Toronto Area. Specifically, the Tories selected pieces of land owned by a tight circle of well-connected developers, a move that potentially created billions of dollars of wealth for the builders with a stroke of a pen while slashing environmental protections.

The Greenbelt changes on their own were met with outrage. Less than two weeks after they were announced, when The Narwhal and the Toronto Star revealed that developers with Progressive Conservative ties were the main beneficiaries, it touched off a scandal that would unfold over the course of 2023 and eventually engulf Ford’s government.

All told, by the time the premier undid his mistake in that parking lot, it had cost him two ministers, two senior staffers and an immeasurable amount of public trust. It left him with almost nothing to report in terms of housing construction, but an RCMP investigation hanging over his head.

How did it all fall apart so quickly? This is how the scandal unfolded, told through freedom of information documents, a report by former auditor general Bonnie Lysyk and a second by Integrity Commissioner J. David Wake, which included quotes from the players involved.

The Narwhal reached out to the premier’s office, MPP Steve Clark, Clark’s former chief of staff Ryan Amato, multiple developers and several others mentioned in this story. None agreed to an interview.

In retrospect, Ford showed his cards on the Greenbelt back in 2018. He outlined not only what he wanted to do (“open a big chunk of it up”) and at whose suggestion (“some of the biggest developers in this country,” who coincidentally stood to make big money from the approach), but also the belief at the core of it — a certainty, contrary to the evidence, that the Greenbelt stood between Ontarians and affordable housing.

“We will open up the Greenbelt,” a genial-looking Ford said at the 2018 campaign event, to a room of true believers. “Not all of it, but we’re going to open a big chunk of it up and we’re going to start building, and making it more affordable and putting more houses out there.”

The Greenbelt, created by the Dalton McGuinty government in 2005, has always had critics. But it is a popular piece of public policy: in 2021, polling commissioned by the non-profit, provincially funded Greenbelt Foundation showed 84 per cent of those surveyed consider the protected area a “source of pride.” It’s home to favourite hiking spots, host to farms that grow Niagara wine grapes and Holland Marsh carrots, heralded by signs along the sides of highways. It sequesters carbon, and its green spaces absorb rainwater and snowmelt that might otherwise become floods.

Even people who don’t know the ins and outs of the policy, or its importance to the environment, have some sense that it’s there and off-limits to builders. So once the Ontario Liberal party released a video of the campaign event ahead of the 2018 provincial election, backlash was so swift and furious that Ford had to walk it back.

“Unequivocally, we won’t touch the Greenbelt,” Ford said in a video posted to his social media channels. “I’ve heard it loud and clear, people don’t want me touching the Greenbelt, we won’t touch the Greenbelt.”

Within a year of winning that election, the Progressive Conservatives took another stab at the idea with a bill that would’ve made it easier to build on the Greenbelt. Once again, in the face of overwhelming pushback, the government reversed course and spent the next two years promising up and down to not touch the protected area. To make it bigger, if anything.

In December 2021, an internal memo penned by public servants painted a sunny picture of the Greenbelt growth to come. Then-municipal affairs minister Clark, whose responsibilities included the Greenbelt, had travelled around southern Ontario to tout a modest plan to add more land — mostly publicly owned urban river valleys already off-limits to development — to the protected zone by the 2022 election.

His ministry had considered adding a larger chunk along the rocky Paris Galt Moraine but deemed it too complicated to pull off before the vote. In its next term, the document noted, the government could revisit the moraine while the Greenbelt Council, which advises the province on the protected lands, “could provide advice and shape what the government’s measured approach for growing the Greenbelt could be.”

All along, though, Tory plans put the Greenbelt at risk. Take Highway 413 and the Bradford Bypass, two road projects north of Toronto that would slice through sections of the Greenbelt and drive up the values of nearby land owned by developers — including TACC Group, headed by Silvio De Gasperis, and Michael Rice of Rice Group, later the two biggest beneficiaries of the Greenbelt changes. Other government-aided developments chipped away at the land around the Greenbelt’s edges.

While it might have seemed like the Greenbelt question was settled, in reality, it wasn’t so much off the table as it was simmering on a backburner.

It’s not clear when the Ontario government started laying the groundwork for the Greenbelt land swap it would eventually propose. In one of two watchdog reports that came out of the scandal, an investigation by integrity commissioner Wake, insiders testified that from 2018 to 2022, the government’s position on touching the Greenbelt boiled down to one word: no. But some political staff said they were always aware that position was flexible.

“Jamie Wallace, Premier Ford’s chief of staff from June 2019 to January 2023, said that he was always aware of the Greenbelt as an option for building housing,” Wake wrote in his report, released in August. The commissioner made note of a similar sentiment from Andrew Sidnell, Ford’s deputy chief of staff and head of policy from September 2021 to October 2022, who was aware of the Greenbelt “as a lever to pull,” the report said.

The tide may have started to turn in early 2022 when, Wallace told Wake, he had a conversation with Sidnell and another senior Ford advisor, Amin Massoudi, about tackling lagging housing construction. (Wake said Sidnell didn’t remember this conversation.)

“Mr. Wallace suggested that the decrease in housing starts may have been an impetus for looking at the Greenbelt,” Wake wrote.

The government also moved to control the Greenbelt narrative well before the bombshell cuts. Take its dealings with the Greenbelt Council: in 2020, seven members resigned en masse, citing concerns about the Ford government’s environmental policies and how they could harm the protected area.

Documents obtained by The Narwhal through freedom of information also show that, not long after the resignations, the government barred council members from speaking to the media or the public about their work, reversing years of relative openness. The ministry didn’t answer questions from The Narwhal about its reasoning for the move.

Then, in the months leading up to Ford’s second provincial election, the government abruptly halted its planned Greenbelt expansion. “On April 27, 2022, the day that Housing Ministry non-political public service staff were scheduled to submit the proposal to government decision-makers for final approval, they were informed that the government was no longer proceeding with the Growing the Greenbelt project,” wrote former auditor general Lysyk in her August report on the issue.

Ford’s Progressive Conservatives also didn’t repeat their Greenbelt promises on the campaign trail, and some developers took notice — including the De Gasperis family of TACC Group, which eventually succeeded in getting more of their land removed from the Greenbelt than any other developer. “From that silence, she saw an opening,” Wake wrote of Alana De Gasperis, who he interviewed for his report.

Alana’s father Silvio De Gasperis, the head of TACC, also took the hint, Wake’s report said: “This suggested to him there might be an opportunity to revisit the government’s Greenbelt policy.”

The De Gasperises were right: while Ford was out winning votes through May and early June 2022, Ford’s head of housing policy, Jae Truesdell, and two other senior staffers were making plans to re-open the idea of removing land from the Greenbelt. The justification would be Ontario’s housing crisis, despite a glut of evidence that available land wasn’t the crux of the problem. In February 2022, a provincially appointed housing task force had pinpointed bigger obstacles, including inflation and available labour — an analysis later backed up by municipal officials in several regions and voices from the Housing Ministry itself. But that didn’t stop the premier.

There’s still plenty the public doesn’t know about what happened between the June election and Nov. 4, 2022, the day the Ford government announced it would cut into the Greenbelt. Much is disputed, down to basic questions of who knew what and when. Some people involved have contradicted themselves, or given accounts of meetings that others say never happened.

What is clear, though, is that the original order to look at opening the Greenbelt for development was authorized by the premier himself.

For months, Ford and his office were evasive about where that order originated. They said bureaucrats picked the specific pieces of land slated for removal, and that Ford and his cabinet only saw the final proposal in fall 2022, days before they made it public. But they didn’t explain how public servants came to the project in the first place.

That narrative started to look different last spring, when The Narwhal obtained heavily redacted documents indicating Ford had given feedback on a post-election slide deck discussing, among other things, changes to the Greenbelt, in late June 2022. Ford rebuffed the idea that his office had talked about the protected area that summer — “I want to categorically say no. It wasn’t discussed,” he said, responding to The Narwhal’s reporting. Later, Ford’s office added that while the premier gave feedback on the document, it wasn’t about the Greenbelt part.

It’s still not clear what that document was, what it said about the Greenbelt and what Ford’s feedback was. But Ford’s office did, in fact, discuss the possibility of opening the Greenbelt around the same time it circulated the slide deck, reports from the auditor general and integrity commissioner eventually showed. Ford himself also approved the final order to do so before it went out. The direction came in a document called a mandate letter, a set of instructions given from a premier to a minister not long after they’re sworn in, laying out what the priorities for their portfolio should be.

Before Ford, mandate letters were pretty banal— previous Ontario governments made them public by default, which means they were rarely revelatory. But the Progressive Conservatives threw out that playbook in 2018 and have fought for years to keep theirs confidential, even taking CBC to the Supreme Court to avoid releasing them.

The public only knows the Greenbelt order was in Clark’s mandate because the offices of the integrity commissioner and auditor general have the power to compel the province to show the letters.

Commissioner Wake in particular found it was Truesdell and his team that prepared a slideshow of ideas for the mandate letters. It’s not clear if this slide deck is the same one obtained by The Narwhal, which was entirely redacted. But according to the commissioner’s report, Sidnell, Wallace and Massoudi briefed Ford on the slideshow Truesdell had worked on, and the premier gave it the green light, making its direction clear in the mandate letter he sent to then-housing minister Clark.

“In fall 2022, complete work to codify processes for swaps, expansions, contractions and policy updates for the Greenbelt,” the June 29, 2022, mandate letter signed by Ford read.

“In addition, conduct a comprehensive review of the mandate of the Greenbelt Council and Greenbelt Foundation. This should include a comprehensive plan to expand and protect the Greenbelt.”

When Clark received it, he knew the task was significant, though Wake found that the premier’s office and the minister had different understandings of what the letter meant. Clark and his chief of staff, Amato, thought they’d been ordered to develop and implement a policy quickly, while Ford and his staff told the commissioner they only wanted Clark and Amato to explore the possibility.

In the days after Clark received the letter, he spoke to Wallace, Ford’s chief of staff, about it, according to Wake. Then he spoke to Ford himself. Wake’s report didn’t include much about those conversations, except what Clark took away: “Ultimately at the end of the day, it’s my job as minister to take the mandate letter and provide recommendations on the mandate letter,” Clark said, according to the report. “Ultimately, it’s cabinet’s decision whether those items move forward or not.”

Enter one of the main characters of the Greenbelt scandal: Amato.

Amato started his job as Clark’s chief of staff in early July, about a week after the minister received the mandate letter. He had spent the last few years working for then-transportation minister Caroline Mulroney while she worked to advance Highway 413 and the Bradford Bypass. As Mulroney’s director of stakeholder relations, he was brought into the orbit of Rice and Silvio De Gasperis, developers who owned lands close to the planned highways.

Amato spent much of the summer “drinking from a firehose” as he learned the responsibilities of his new job, he told Wake, according to the report. Part of that was trying to figure out what, exactly, the vaguely worded mandate letter would mean for the Greenbelt.

In his report, Wake found that no one seemed to think opening the Greenbelt was actually going to happen, at least at first. Amato told Wake he didn’t realize the idea was serious until an early September 2022 meeting in the premier’s office. The prospect couldn’t have been far from his mind a week later at a pivotal dinner, when according to Wake’s report, both Silvio De Gasperis and Rice approached him to ask for Greenbelt carveouts.

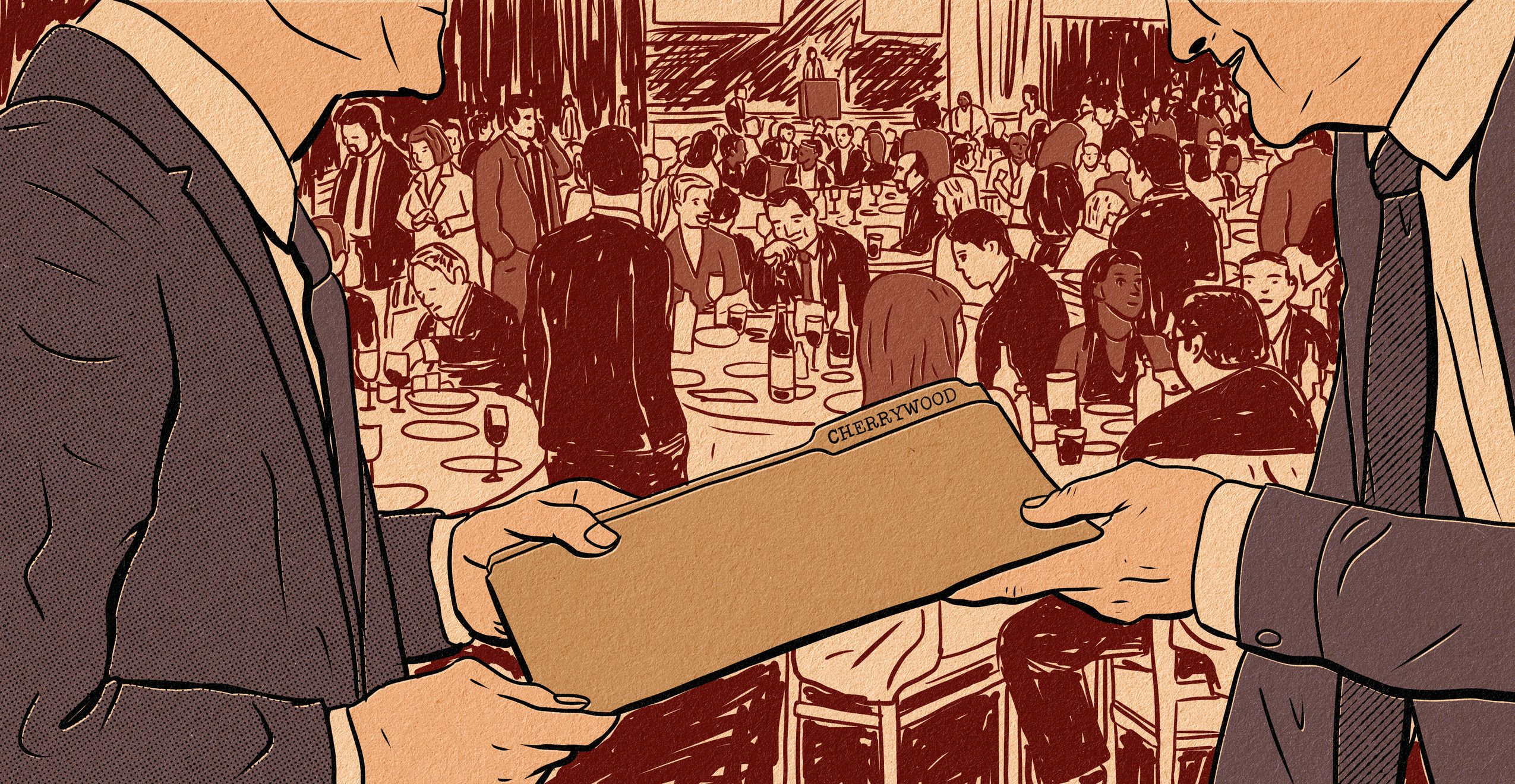

The dinner — the significance of which was first revealed in Lysyk’s audit — was hosted by the Building Industry and Land Development Association, a lobby group for 1,200 companies in the Greater Toronto Area also known as BILD. The group works closely with the provincial government on land use and housing policy, and it’s not uncommon for chiefs of staff like Amato to rub elbows with its members at events. This one was held at a banquet hall in Woodbridge, where many powerful homebuilders have their headquarters. Tickets ran between $175 and $300 and the scant public photos of it online show developers in business attire, posing against a backdrop with the association’s logo.

It was there that Silvio De Gasperis took Amato aside. The developer is a longtime Progressive Conservative donor whose company, TACC — an acronym that stands for “the amazing construction company” — already stood to benefit from a few Ford government policy decisions, like Highway 413 and some special zoning orders issued by Clark to speed up certain development projects.

After the former Liberal government established the Greenbelt in 2005, Silvio De Gasperis fought the policy in court for years in an attempt to keep land he owns in Pickering, east of Toronto, out of it. He lost; the site, which he called Cherrywood, became the Duffins Rouge Agricultural Preserve and had been off limits to development ever since. The developer had long felt that Cherrywood was the biggest disappointment of his career, Wake wrote.

“I have a package I want you to take a look at — there was an injustice done at Cherrywood and I want you to take a look,” Silvio De Gasperis said he told Amato, according to Wake’s report.

A second developer, Rice, also approached Amato that night. Amato initially told Wake he wasn’t sure if he had met Rice before the event, but Rice said they had met at a handful of political fundraisers — including one he organized for Mulroney while Amato worked for her, where the two had “very limited contact,” according to Wake.

Rice had been working for months on the $80-million purchase of nearly 700 acres of Greenbelt land in King Township, just a bit north of the event. The sale was due to close the next day. “Hey, if you guys are looking at the Greenbelt lands, I have something great that is the site you need to look at,” Rice told Amato, according to Wake’s report.

It was a critical night. In the end, land that was partially or fully owned by either Silvio De Gasperis, Rice or their companies would account for 92 per cent of the land removed from the Greenbelt, the auditor general found.

Sometime around this period, according to Wake’s report, Amato asked Ford directly for clarity on the Greenbelt during a meeting where Clark and another Ford aide, Patrick Sackville, were present. Amato couldn’t tell Wake exactly when it happened, but said he wanted clarity quickly because he felt the move would be politically unpopular and it would be best to get it done as long before the next election as possible.

“Respectfully sir, are we, is this something that needs to be done or is this one of the things we might not do?” he asked, according to Wake’s report.

“Mr. Amato does not recall who responded, whether it was Premier Ford or Mr. Sackville, and what words were spoken, but said he left that meeting with a clear understanding that something needed to be done,” Wake wrote. Ford, Sackville and Clark denied to Wake that this meeting happened, but on Sept. 15, 2022, the day after the building industry gala, Amato sent a series of texts to another Clark staffer that seemed to recount the conversation. “They are very serious,” Amato wrote in one text obtained by Wake, referring to Ford and Sackville.

Amato told Wake that soon after the meeting with Ford, he told Clark to “Leave it with me.” Thus Amato embarked on his Greenbelt mission.

On Sept. 21, 2022, Amato told two senior public servants in the Housing Ministry — then-deputy minister Kate Manson-Smith and assistant deputy minister Sean Fraser — the government definitely wanted to consider removing specific sites from the Greenbelt, and that they had just over a month to come up with a plan. The first two sites he told them to look at were Silvio De Gasperis’ Cherrywood site and the property Rice had just bought in King.

What ensued was a process Wake would later label as “chaotic and almost reckless.” Amato was the lead, Wake found: acting mostly alone and undirected, he was the liaison between political staff, public servants and developers who reached out to him about Greenbelt sites they wanted freed up for development.

One central question in the scandal has been whether developers with longstanding ties to Ford and his government were outright told the Greenbelt was being opened. As far as Wake could tell, no one within the government spilled the beans, but Amato’s actions were an indirect tip-off. Silvio De Gasperis and other developers had been making regular Greenbelt removal requests for years, always hearing an immediate no. When Amato instead asked for more details, they knew something was changing, spurring what Amato called a developer “rumour mill,” according to Wake.

“The development community is a lot like high school, they all start talking to each other,” Amato said, according to the report.

As requests came in, Amato passed them along to a tight group of public servants — the Greenbelt project team. The process started out with guidelines for picking sites to remove from the protected area, including one meant to protect environmentally sensitive features like wetlands and agricultural land. Amato dropped that criteria, feeling it was too complicated, according to Wake’s report. He also altered the boundaries of some proposed sites to allow them to go forward, Lysyk found. Public servants also told Amato they didn’t have time to assess whether the properties had sewage hookups or other infrastructure needed for housing construction, so Amato agreed to drop that guideline too.

One public servant told Wake “it was very hard to keep a handle on the consistency of the criteria because they weren’t very … what is the word I’m looking for? They weren’t very evidence-based.”

The bureaucrats didn’t question where Amato’s property suggestions, many delivered on USB drives he received from developers, were coming from: “He didn’t say anything about that and we didn’t ask,” Fraser is quoted as saying in Wake’s report.

Some, including Manson-Smith, told Wake they were under the impression Amato was acting on orders from the premier’s office, which the commissioner concluded was “deception.” Typed notes from one ministry official cited in Wake’s report said Amato told colleagues three Greenbelt sites “were given straight from the premier.” Speaking to Wake later, Amato denied this, according to the report, saying, “That is not true.”

In the end, Amato appears to have suggested all but one of the sites removed from the Greenbelt, Wake found.

Without the investigations by the integrity commissioner and auditor general, much of the government’s efforts would have been shielded from public scrutiny. Aside from Amato, most bureaucrats worked under non-disclosure agreements as the government wished to keep the politically-sensitive plan confidential. Ministry officials told Wake they avoided email and used video chat instead. Meetings in Amato’s calendar were unlabelled — he later told Wake he either didn’t recall the topics, the meetings weren’t related to the Greenbelt or he didn’t attend them. There are also no records of pivotal conversations Amato had with developers about basic facts like how many homes could be built if their lands were removed from the Greenbelt. Amato kept no notes, Wake said, but added up estimates on a calculator.

Freedom of information documents obtained by the advocacy groups Ecojustice and Environmental Defence and released earlier this fall detailed further secrecy measures: the Greenbelt project team circulated digital documents through screenshots and prepared communications materials in live editing sessions, both measures that would leave a minimal paper trail. They also took steps to prevent hard copies of documents from being leaked, using unique watermarks so their source could be traced.

Things started to get messy as the process steamrolled toward its conclusion, and Amato’s secrecy measures started to backfire, occasionally putting him in conflict with staff like Truesdell in the premier’s office who didn’t know what he’d been doing.

Clark, meanwhile, stayed out of it. The housing minister had a lot going on: the Greenbelt was one of three huge pieces of legislation he introduced in the span of a few weeks, and a close family member was hospitalized through the fall.

He also wasn’t keen about the task at hand, later telling Wake he wasn’t “in a very happy mood” about being asked to reverse decisions he made in the Ford government’s first term. The integrity commissioner concluded Clark only got involved in late October — he asked for one site to be changed to preserve more of a wetland, then brought the entire Greenbelt land swap proposal to cabinet a week later.

“It may seem incredible that minister Clark would have chosen to stick his head in the sand on such an important initiative being undertaken by his ministry but I believe that was exactly what he did,” Wake concluded.

Ontarians may never know what happened inside the cabinet room when Ford’s ministers, the same group who later stood behind him in Niagara as he reversed the plan, looked over the proposal. Cabinet’s deliberations are confidential for two decades, so only those who were there know what questions they did or didn’t ask and whether anyone was worried the whole thing would be politically radioactive. But they signed off.

In the end, Amato’s Greenbelt project team decided to remove protections from 15 snippets of Greenbelt land, promising to enable the construction of 50,000 homes, a drop in the bucket compared to the 1.5 million the province estimates it needs to tackle Ontario’s housing crisis. By making the 7,400 acres of properties developable, the plan also made them far more valuable, potentially creating over $8 billion of dollars of wealth for their owners, according to Lysyk’s estimate. Builders would have a deadline of 2025 to get shovels in the ground, lest the ministry return any unused land to the Greenbelt.

The premier’s office also signed off on a plan to compensate for the lost land by reviving the 2021 Greenbelt expansion proposal. It would include the urban river valleys and a small piece of the larger Paris Galt Moraine, which would add 9,400 acres to the protected area. Like the urban river valleys, the conservation value of the Paris Galt Moraine addition was less than ideal, since it was already protected under other mechanisms. Internal government mapping obtained by The Narwhal through freedom of information shows the part added to the Greenbelt is a tiny sliver of the overall moraine, and Lysyk concluded it was chosen “without consideration” for the natural features of the land and against the recommendations of public servants.

By the time the proposal went online on Nov. 4, 2022, with no press conference or fanfare, the scandal over Ford’s broken Greenbelt promise had already been set in motion.

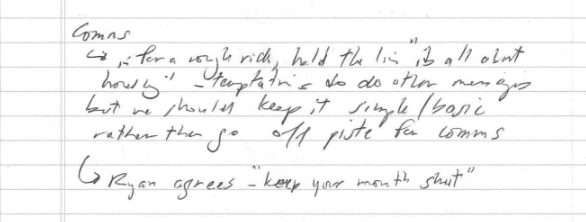

Within two weeks, The Narwhal and the Toronto Star jointly published an investigation detailing developer landholdings in the 15 sections removed from the Greenbelt. Later, ministry staff notes made public would depict how the revelations went over inside the government: they quote Amato — who didn’t respond to previous questions from The Narwhal about the notes — calling the investigation a “hit piece,” and saying “keep your mouth shut” while noting the government was going to be “in for a rough ride.” And they were.

Clark and his staff tried to dodge questions about how the lands were selected, but as public outcry grew, his office said they hadn’t tipped off developers about the plan. By mid-December, when the legislature locked in the changes, opposition parties were howling for Lysyk and Wake to investigate. Over the course of a single roller coaster day in January, both announced they would. The Ontario Provincial Police, too, quietly started mulling whether to launch a probe.

For a while, the government was getting an earful from all sides. As Lysyk and Wake worked on their reports, the public protested, including one weekend where 20 rallies were held across the province. Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation said it was considering taking legal action over the government’s failure to consult them. Developers left out of the Greenbelt project sent in a flurry of requests for Clark’s ministry to open up even more protected land.

Parks Canada raised red flags about how housing construction on one particular piece of opened land — Silvio De Gasperis’ Cherrywood, in the Duffins Rouge Agricultural Preserve — could affect the sensitive species and landscapes of Rouge National Urban Park, which sits next door. Federal Environment Minister Steven Guilbeault took those concerns a step further, threatening to stop or delay projects on former Greenbelt lands.

Scrutiny over the government’s ties to developers intensified. In February, Global News reported some developers had attended a pre-wedding stag-and-doe party for one of Ford’s daughters in August 2022, in the months leading up to the Greenbelt changes. Tickets were $150 and attendees were encouraged, Global reported, to give additional cash gifts to the happy couple. The Toronto Star reported one landowner who benefited from the Greenbelt changes, Shakir Rehmatullah of Flato Developments, was among the guests at the wedding. In late June, The Trillium reported that Massoudi, the Ford aide, and Tory MPP Kaleed Rasheed had gone on a Las Vegas trip with Rehmatullah in 2020, along with Truesdell, who wasn’t working for the government at the time.

In the background, developers worked to solidify construction plans as quickly as possible: some snapped up even more former Greenbelt land in the early summer, a $173-million signal they were sure they’d reap profits large enough to make the investment worth it.

All the while, as the watchdogs investigated and rumours swirled about USB drives and confidentiality agreements, Ford remained defiant: “We’re building homes on those pieces of property, sure as I’m standing here today,” he fired back after Guilbeault’s critique.

That bravado only started to dissipate in early August, when Lysyk finished her report.

The auditor general’s report landed on Aug. 9, and went off like a bomb. It was the first time the public learned how the Greenbelt parcels that lost protections were chosen — Lysyk introduced Amato, broke the news of the building industry dinner and confirmed suspicions that the process was flawed. She also alleged that political staff had “regularly” been deleting emails or using personal accounts to talk to stakeholders, hiding what they had been doing.

Lysyk’s report was also a thorough debunking of the story the Ford government had told about its motivations — not only was the process developer driven, but the land wasn’t necessary or particularly well-suited to build new homes, she found.

“The process was biased in favour of certain developers and landowners who had timely access to the housing minister’s chief of staff,” Lysyk told reporters, though she concluded that Clark and Ford did not know what Amato had been doing.

In an odd press conference the day of the report’s release, Ford and Clark stood at two lecterns several metres apart as reporters lashed them with questions, cameras panning back and forth between them. Ford insisted the “buck stops with me” and said he took “full responsibility” for what Lysyk documented while also declining to fire anyone involved. Clark dodged when asked if he or Amato would resign, saying, “I appreciate the confidence the premier has in myself and my staff.” Both accepted Lysyk’s recommendations — save the most important one, which was to return land to the Greenbelt.

So began one of the most bizarre, chaotic months in Ontario politics in recent memory.

The next day, Ford flip-flopped. He started contesting Lysyk’s findings, telling reporters “no one had preferential treatment.” At the same time, his office sent a memo to chiefs of staff and deputy ministers to remind them to follow ethics rules. Public protests erupted almost immediately, with people picketing outside the offices of their local MPPs in the summer heat in cities across southern Ontario, including at annual Ford Fest events.

Opposition critics questioned whether Amato really was the mastermind the reports portrayed him to be, or whether the issues might extend higher. “I’ve worked in a premier’s office. It’s not how things work, not on a decision of this size,” then-interim Liberal leader John Fraser said. “Ultimately Ryan doesn’t make the decision, the minister makes a decision. The premier makes a decision.”

As backlash reached a fever pitch, Amato resigned on Aug. 22 with a letter disputing his portrayal in Lysyk’s report, and lawyered up. “I am confident that I have acted appropriately, and that a fair and complete investigation would reach the same conclusion,” said the letter, which was obtained by multiple news outlets but hasn’t been independently verified by The Narwhal.

The very next day, the Ontario Provincial Police announced it had punted the review of the situation — not an investigation, not yet — to the RCMP, citing an undisclosed conflict of interest.

Wake’s report landed a week later in all its devastating detail, introducing new plotlines and characters that cranked up the drama. Like Mr. X, an unidentified and allegedly unregistered lobbyist who Wake said was promised up to a million dollars if he was able to successfully get a Greenbelt property in Clarington, Ont., approved for development. Part of the money was described as a “Greenbelt fee” in a contract seen by Wake.

The commissioner also dove into the nitty gritty of the Las Vegas trip MPP Rasheed, Truesdell and Ford aide Massoudi took at the same time as developer Rehmatullah. Massoudi and Rasheed told the commissioner they traveled to Vegas with Truesdell, and Massoudi and Rasheed briefly ran into Rehmatullah in the lobby of their hotel. Rasheed said he covered the cost of hotel and flights for himself, Massoudi and Truesdell, who reimbursed him.

Things went from bad to miserable to calamitous for the Progressive Conservatives. In a surreal twist, the premier responded to the integrity commissioner’s findings in a press conference held inside a high school auto shop classroom, with a Ford Escape behind him and a poster that read “power corrupts” on the wall facing him, out of sight of the cameras. He said he didn’t give “two hoots” about developers. Finally, he lashed out at a reporter who questioned his culpability in the scandal, attempting to stick to his line about the housing crisis.

“You have a nice home down the street, but guess what?” Ford said. “There are hundreds of thousands of people that don’t have your opportunity, that don’t have the good paying job you have. That’s the difference.”

The Ford government announces its plan to remove properties from the Greenbelt.

The Narwhal and the Toronto Star reveal which developers own much of the land included in the government’s plan.

The Ford government finalizes the Greenbelt land swap, removing 15 slices from the protected area and adding in other land that was already off-limits to development.

Ontario Provincial Police say investigators are mulling whether to launch an investigation into the Greenbelt changes after receiving over a dozen complaints.

In a double whammy, then-auditor general Bonnie Lysyk and Integrity Commissioner J. David Wake both announce investigations into the land swap.

Lysyk publishes her bombshell Greenbelt report, revealing the alleged role of housing ministry chief of staff Ryan Amato in the scandal.

Amato quits, but says in a resignation letter that he was “unfairly depicted” in Lysyk’s report. The next day, Ontario Provincial Police punt their Greenbelt review to the RCMP.

Wake publishes his report, concluding then-housing minister Steve Clark violated ethics rules. Clark resigns a few days later.

Doug Ford announces the reversal of the Greenbelt removals, but leaves the 2022 additions in place.

The RCMP officially launches an investigation into the Greenbelt changes.

Clark, who Wake had singled out as having violated ethics rules by remaining ignorant about the Greenbelt project happening on his watch, spoke to reporters a few hours later. He was the polar opposite of Ford: he looked downtrodden, somber, apologetic. At times, his voice seemed thick.

“You’re not seen as an incompetent person,” one reporter said. “But when you read that report, that’s what it looks like. The only way it makes sense to people who know you is if you thought this was being done because the premier wanted it, because his people were taking care of it. Is that how you saw it at the time?”

“Did the premier set you up to fail?” another asked.

“I accept responsibility,” Clark said over and over again, dodging the questions even as he said he was sorry. “I apologize to Ontarians.”

It was his last press conference as minister. He stepped down a few days later, over the Labour Day long weekend. Even that didn’t put a rest to the madness, or the sense that the wheels were coming off.

As Ford kept trying to say that all he wanted to do was build more homes, the public largely didn’t buy it. A disastrous late-August poll showed a majority of Ontarians believed the Greenbelt land swap was “corrupt.” Tory voters called in to radio shows to sound off about the worsening scandal, some vowing to never vote Progressive Conservative again. Ford announced a “Greenbelt review” that could result in the return of some protected land, which sounded OK — until he said it was possible the process could open up even more land for development, a suggestion met with more public uproar.

Soon after, The Trillium raised questions about the Vegas trip, and whether Massoudi, Truesdell and Rasheed had given Wake accurate information. Massoudi had booked a “good luck ritual” at the spa of the hotel they stayed at, but on a different date than he’d told Wake he was there, the reporting showed. Building on those findings, CTV revealed Rasheed and Rehmatullah were at the spa at the same time, clashing with Rasheed’s comment to Wake that he was “surprised” to run into the developer in the lobby during the trip. A spokesperson for Rasheed said the minister had “mistakenly” shared incorrect information with Wake from an earlier itinerary, after which the trip was rescheduled. Rehmatullah and Truesdell haven’t publicly responded to claims they might have given the commissioner the wrong information.

The MPP got the “good luck ritual” too, while Rehmatullah got a custom massage, CTV reported. Truesdell did not get a massage at all.

The frenzy became a circus: within 72 hours of CTV’s story, Rasheed resigned. Truesdell stepped down too. Ford had allowed the crisis to deepen. He had no choice but to take it all back at the Tories’ Niagara cabinet retreat.

In 2018, developer Michael De Gasperis hosted Ford and Progressive Conservative MPP Stephen Lecce in a private luxury suite at a Florida Panthers’ hockey game in Miami. De Gasperis is the younger brother of Silvio De Gasperis, and has been listed as a vice president at TACC. After a 2021 Toronto Star and National Observer story, spokespeople for Ford and Lecce said they paid for their own tickets and didn’t discuss government business.

Key figures in Ford’s orbit went to Las Vegas in early 2020 at the same time as would-be Greenbelt developer Shakir Rehmatullah: former cabinet minister Kaleed Rasheed, longtime Ford aide Amin Massoudi, who has since left government, and Jae Truesdell, who wasn’t working for Ford at the time but became his head of housing policy in early 2022. After news reports raised questions about whether their testimonies to the integrity commissioner about the trip were accurate, both Rasheed and Truesdell resigned. Massoudi and Rasheed said they traveled to Las Vegas with Truesdell and Massoudi and Rasheed briefly ran into Rematullah in the lobby of the hotel.

Perhaps the most controversial event highlighting the government’s ties with developers was a pre-wedding stag-and-doe for Ford’s daughter in August 2022, months before the Greenbelt changes. Several developers paid the $150 per person ticket price, including Rehmatullah, who went to the party, and Sergio Manchia, who didn’t. The integrity commissioner concluded it was “more likely than not” someone tipped Rehmatullah off about the Greenbelt changes, but said it would be “fanciful” to point the finger at the premier and events surrounding the wedding.

“Our caucus, they shared with me what they’ve heard in their communities,” he told reporters in the parking lot by the Margaritaville, almost 12 months to the day that Amato embarked on the Greenbelt project.

“I want the people of Ontario to know I’m listening.”

Maybe they heard him. Since the reversal, Ford’s poll numbers have rebounded. But his troubles aren’t over: the RCMP officially launched an investigation in late September. The Mounties haven’t said anything publicly about the scope of that probe, what kind of criminality they suspect might have been involved or how long their investigation could take.

Wake’s work on Greenbelt-related issues is on hold while the RCMP investigates. But he could eventually release more reports — like one on Amato, which Wake has said he’s considering, or the premier’s use of his personal cellphone for government business. And speaking of record keeping: a third provincial watchdog is looking into Lysyk’s allegations that political staff regularly deleted records, which will become relevant as the government handles reams of freedom of information requests about the scandal. It could be years before the records involved are made public, if ever.

The government’s bill to officially make the Greenbelt whole again — introduced in mid-October and passed just before the holidays — included clauses meant to block any potential lawsuits. Minotar Holdings, the owner of the one affected property that was selected by public servants instead of Amato, has filed a court application anyway, alleging the bill violates the “constitutional principle of the right of law.” Minotar has argued for years that its land was wrongfully included in the Greenbelt, and it also sued the province over the issue in 2017.

As it turns out, the Greenbelt may be only the beginning of the Ford government’s development policy reversals. Paul Calandra replaced Clark as municipal affairs and housing minister and has spent much of his time undoing his predecessor’s work. He started by walking back plans to expand several southern Ontario communities’ urban boundaries, a move that would have enabled housing development on farmland to the benefit of many of the same figures highlighted in the Greenbelt scandal. Calandra has also announced he’s mulling whether to cancel over a dozen special land zoning orders issued to fast-track development proposals, including some Clark gave to Flato.

The Greenbelt might be safer today than two years ago — and slightly bigger, as the urban river valleys and Paris Galt Moraine additions stand. And the Ford government has committed to a variety of reforms, including an overhaul of lobbying rules. But many more questions remain about what actually happened inside the government and whether Ford and his team have learned from it. As their ruinous year drew to a close, it wasn’t clear any overarching lessons about coziness with industry and deference to developers had sunk in.

In mid-December, Calandra gave a speech to hundreds of developers at an industry event hosted by the Building Industry and Land Developers Association, the same organization that threw the gala that helped catapult Amato into a world of Greenbelt trouble. According to the Toronto Star, the new housing minister was there to deliver a personal apology.

“I am sincerely sorry for the difficulties we have caused you and the industry over the last number of months,” he told the room. Then, he turned specifically to Silvio De Gasperis.

“I’ve never met him to be honest, but if Mr. De Gasperis is here … there he is, let me just say this … I am particularly sorry for how you and many of you have been cast,” the Star quoted him as saying.

“I am extremely proud of what you have accomplished and what all of you have accomplished. Building homes should not be something that you are ashamed of and we’re going to support you and make sure that that narrative changes.”

“So to you, sir, I’m very sorry,” he said, adding, “I’m sorry that we’ve never met.”

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. When I visited my reserve, Moose Factory,...

Continue reading

Xatśūll First Nation is challenging B.C.’s approval of Mount Polley mine’s tailings dam raising. Indigenous...

As the top candidates for Canada’s next prime minister promise swift, major expansions of mining...

Financial regulators hit pause this week on a years-long effort to force corporations to be...